By Aldon Thomas Stiles, California Black Media

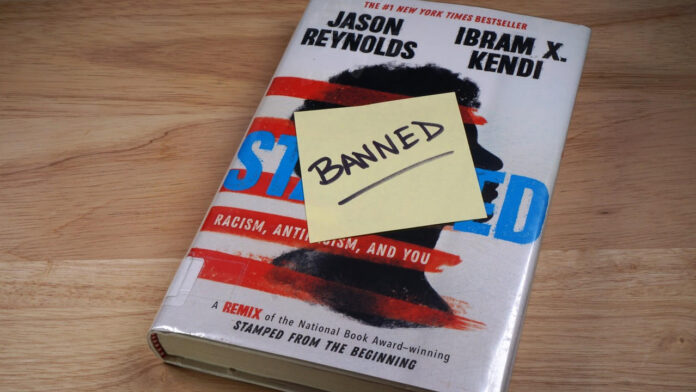

Nationwide, book banning is on the rise. It’s reached a 20-year high, according to the American Library Association and Unite Against Book Bans.

Some of the books that have been banned include titles like “Beloved” by Toni Morrison, “I Am Enough” by Grace Byers and “Maus” by Art Spiegelman.

“It is also worth noting that most challenged books feature LGBTQIA-related topics or are by BIPOC authors,” Kadie Seitz, a librarian at the Los Angeles Public Library who focuses on youth services, wrote on the organization’s blog.

Troy Flint, Chief Information Officer at the California School Boards Association (CSBA), pointed out that book bans are not happening in California at the same level as in other states but cautioned that there is still cause for concern.

“There are a wide range of books that have been banned in a number of districts, although it’s a relatively small number,” Flint said.

“However, this is a concerning trend because the actual effects are on a much bigger scale than they might appear,” he continued.

Gov. Gavin Newsom says the bans are largely partisan.

“Republicans are trying to destroy public education. Banning history. Banning books. Banning student speech. And now Betsy DeVos is admitting it,” Newsom tweeted last month, responding to the former U.S. Secretary of Education declaring that she believes the nation’s Department of Education “should not exist.”

In March, the governor tweeted a picture of himself reading several frequently targeted books with the caption, “reading some banned books to figure out what these states are so afraid of.”

Flint also spoke about some of the perceived political motivations for the renewed vigor of book banning efforts across the United States.

“Partisan interest has been driving these kinds of decisions as opposed to objective assessments of material on the basis of what children can handle and what they should learn,” Flint said.

In 2020, the liberal leaning city of Burbank banned five well-known titles: “Huckleberry Finn” by Mark Twain, “The Cay” by Theodore Taylor, “Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry” by Mildred D. Taylor and “Of Mice and Men” by John Steinbeck.

The Burbank Unified School District objected to the inclusion of these books in their schools’ curriculum because according to them these titles “cast Black people in negative, hopeless, and secondary roles; and all but one are written from the lens of a White author.”

The same year Burbank Unified made its decision to challenge the use of five books, Pennsylvania’s Central York School District banned eight times the number of books and educational materials banned by the California district, including Brad Meltzer’s “I Am Rosa Parks” and the James Baldwin centered documentary “I Am Not Your Negro” directed by Raoul Peck.

While all the 40 books and multimedia articles that the Central York School District banned were either written by authors of color or relate to race, the board insists that the motivation for its controversial decision was the “content” of the material — not the race of the material’s content creator.

Flint argued that this trend of widespread book banning could lead to complications at the local level for educators and institutions who want to avoid legal trouble.

He warned that districts that ban several books in similar demographic target audiences could risk “self-censorship at a classroom and district level, even if some books have not been officially banned.”