(CNN) — As she fought back tears, CNN anchor Sara Sidner revealed her cancer diagnosis to the world.

“Just take a second to recall the names of eight women who you love and know in your life. Just eight. Count them on your fingers. Statistically, one of them will get or have breast cancer. I am that 1 in 8 in my friend group,” Sidner said live on the air Monday.

“Breast cancer does not run in my family, and yet here I am with stage III breast cancer. It is hard to say out loud. I am in my second month of chemo treatments and will do radiation and a double mastectomy. Stage III is not a death sentence anymore for the vast majority of women,” Sidner said. “But here is the reality that really shocked my system when I started to research more about breast cancer, something I never knew before this diagnosis: If you happen to be a Black woman, you are 41% more likely to die from breast cancer than your White counterparts.”

Even though Black women in the US have about a 4% lower incidence rate of breast cancer than White women, they are more likely to die from the disease, according to the American Cancer Society. Since 2019, breast cancer has been the leading cause of cancer death for Black women.

The racial disparity in breast cancer deaths varies from state to state, said Dr. William Dahut, chief scientific officer for the American Cancer Society.

“If you go to some states like Arizona, Arkansas, Illinois, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, it’s about 50% higher, and in the District of Columbia, it’s actually twice as high,” Dahut said.

“And under the age of 50, it’s twice as high. So the mortality differences are greatest for young women in their 20s, and by the time you reach women in their 70s, there’s a small difference in mortality,” he said. “We do know that Black women are more likely to present with triple-negative breast cancer, so they’re about twice as more likely to be diagnosed than White women. And then if you talk about more advanced disease, 39% of Black women are diagnosed with advanced disease, compared to 29% of white women.”

Triple-negative breast cancer refers to certain characteristics of the cancer cells. It tends to grow and spread faster, has fewer treatment options and often has a worse prognosis than other forms of the disease, according to the American Cancer Society.

Racial disparities in breast cancer are probably due to a “combination of biological and socioeconomic factors” that are the result of structural racism, says Dr. Demetria Smith-Graziani, a medical oncologist, breast cancer specialist and researcher-investigator at Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University.

“Black women are more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer at a younger age, and they’re more likely to be diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer, which is a more aggressive type of breast cancer,” Smith-Graziani wrote in an email.

“Additionally Black women are less likely to see primary care doctors regularly compared to white women, and they are less likely to undergo breast cancer screening,” she said. “Once a breast cancer diagnosis is made, Black women have a significantly longer delay to the start of treatment.”

When to screen for breast cancer

Due to the racial disparity in breast cancer deaths, health experts long have debated whether Black women should be recommended for breast cancer screening at younger ages.

One study, published in April in the journal JAMA Network Open, suggests that screening guidelines recommend that Black women start screening at age 42 instead of the current recommendation, 50.

The study found that the rate of breast cancer deaths among women in their 40s was 27 per 100,000 person-years for Black women, compared with 15 deaths per 100,000 in White women and 11 deaths per 100,000 in American Indian, Alaska Native, Hispanic and Asian or Pacific Islander women.

The potential harm of starting mammograms at a younger age is that it raises the risk of a false positive screening result, leading to unnecessary subsequent tests, potential costs and emotional stress. But the researchers behind the study wrote that “the added risk of false positives from earlier screenings may be balanced by the benefits” linked with earlier breast cancer detection.

In May, the US Preventive Services Task Force – a group of independent medical experts whose recommendations help guide doctors’ decisions and influence insurance plans – proposed in a draft recommendation that all women at average risk of breast cancer start screening, every other year, at age 40 to reduce their risk of dying from the disease.

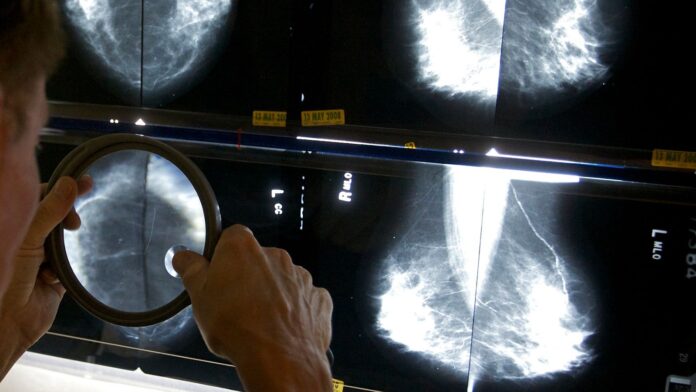

That proposal would be an update to the 2016 recommendation, in which the task force recommended that biennial mammograms, which are x-rays of the breasts, start at age 50 and that the decision for women to screen in their 40s “should be an individual one.”

The draft recommendation is for all people assigned female at birth, including cisgender women, trans men and nonbinary people, who are at average risk for breast cancer. The updates would not apply to those at an increased risk of breast cancer, who may already have been encouraged to screen at 40 or earlier. They should continue to follow the screening practices that their doctors have recommended.

The USPSTF draft recommendation appears to be catching up with what other organizations have been recommending for some time.

The American Cancer Society recommends that women ages 40 to 44 have the option to screen with a mammogram every year, that women 45 to 55 get mammograms every year, and that women 55 and older switch to a schedule of mammograms every other year. The Mayo Clinic also emphasizes that women have the option to start screening with a mammogram every year starting at age 40.

Data released last week by Epic Research, owned by the health care software company Epic, shows that women screened for breast cancer annually have a 17% lower risk of dying from any cause after a breast cancer diagnosis compared with those screened every two years.

The study included data on 25,512 women, ages 50 to 74, who were diagnosed with breast cancer between January 2018 and August 2022 but who were not identified as being at high risk of breast cancer before their diagnosis.

The data also showed that women older than 60, who are Black, who live in more socially vulnerable areas or who live in rural areas had an increased risk of all-cause mortality after a breast cancer diagnosis than women younger than 60, who are White, who live in less socially vulnerable areas or who live in urban areas, respectively.

To assess your own risk of breast cancer, “look at your family history. If you have a sister or a mother or aunt with breast cancer or ovarian cancer, you should definitely consider potentially doing genetic screening for mutations but also undergoing screening at an earlier age,” the American Cancer Society’s Dahut said.

“Women that have been found to have dense breasts have a higher risk of breast cancer – about a 40% higher risk – and they probably need additional screening beyond mammography, maybe need ultrasound or MRI,” he said. “For the average patient, at age 40, they should talk to their physician about annual mammography, and certainly by age 45, everyone should undergo a mammogram.”

Women should check for lumps in the breast during self-examinations but also be mindful of other signs and symptoms of breast cancer.

“Women should look for changes in the color or thickness of the skin on the breast,” Smith-Graziani wrote. “Changes in the appearance of the nipples, discharge from the nipples, pain in the breasts, and pain, fullness, or a lump under the arms.”