By Jessica Kutz, The 19th

When Dollie Burwell, now 74, reflects back on the Warren County protests, she thinks about the Black women who led and supported the protesters.

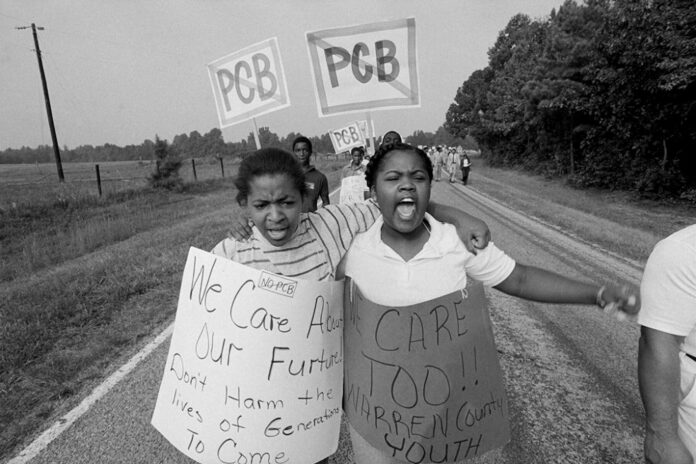

For six weeks in 1982, Burwell and hundreds of others from her predominantly Black North Carolina community marched to block trucks from bringing in soil contaminated with PCBs, a known carcinogen, to a nearby landfill. Burwell, who was one of the leaders of the protests, had approached her congregation at the Coley Springs Missionary Baptist Church about getting involved in the effort and to guide the work in a civil and nonviolent way.

“And so, in the tradition of the Black church, you have a lot of Black women who are leaders,” she said. Black women became very involved in the protests. Many were arrested. Others played a role in supporting the protesters.

“That’s what I’ve been reflecting on,” Burwell said. “Those Black women who fed us, who got up early in the morning and came out at the Coley Spring Baptist Church and cooked food to bring to the marches.”

It’s what kept Burwell, a mother of two, and other residents marching. Burwell was arrested five times during that period for her activism. Even her 8-year-old daughter was arrested once while participating in the marches.

While the community lost the fight against the landfill — the Environmental Protection Agency had approved the permit in 1979 and lawsuits filed by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) failed — the battle helped birth a nationwide movement. Awareness spread around the country that toxic landfills were being placed in predominantly Black and poor communities.

In her years of activism, Burwell became known as the “mother of the movement” — a leading force behind the idea that all communities have a right to a safe and healthy environment. In the succeeding decades, other women — and women of color, in particular — have fought against landfills, petrochemical facilities and fracking operations.

Many of the people who spearheaded the movement saw how far their cries have reached on Saturday, when Michael Regan, the administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency, came to Warren County and announced the creation of a new Environmental Justice and External Civil Rights office at the federal agency.

The new office will include over 200 EPA staff members, both at the agency’s headquarters and in the 10 regional EPA offices across the country. Staff will both bolster Title VI compliance, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color or national origin, and help communities access the $3 billion from the Inflation Reduction Act dedicated to a climate and environmental justice block grant program.

“This new elevation of this office will provide the structure that we need internally, not just on the enforcement side,” said EPA administrator Michael Regan in an interview on Friday. ‘[It will provide] the assurance that as we develop all of our regulations, all of our policies, contracts and procurements, [that] every single thing we do at EPA has an infusion of environmental justice, equity and civil rights.”

For Burwell, who attended the announcement, it felt like a full-circle moment.

At the time of the landfill decision, Warren County residents thought the EPA would protect the community from the toxic waste. “A lot of people were disappointed when the EPA allowed the state to put in the landfill,” she said. “And so 40 years later, having the EPA come to Warren County and recognize the birthplace of the environmental justice movement is a big deal to us, it is a really big deal to us.”

Black women like Burwell have played a key role in shaping the fight for environmental justice from a grassroots level all the way up to how federal agencies are addressing the issue.

“I’ve been on the ground with Catherine Flowers in Alabama, spent time with Peggy Shepard in New York and Dr. Beverly Wright in Louisiana,” Regan said. “We learned a lot from the work that they have been doing over the past 30 to 40 years. And that has been integrated into our thinking and while we are able to be where we are today.”

Flowers is known for her fight to bring attention to the lack of wastewater treatment facilities in rural Alabama; Shepard is the co-founder of WE ACT for Environmental Justice, which fights for environmental health protections both in New York and nationally; Wright is an environmental justice scholar who has been studying the impacts of petrochemical plants on Louisiana, in a part of the state known as Cancer Alley.

All three of these women also sit on the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council, created by the Biden administration to provide recommendations on how to enact policies that address environmental injustice.

“We have a very strong leadership team that is demonstrative of those who have been a part of this movement for a long period of time,” Regan said. “I believe that with these strong women leaders at the table, in a position to make decisions, we’re going to have some very strong solutions for our community.”

The announcement is one of several environmental justice initiatives announced by the Biden administration since last year that signal a shift in how the federal government views and addresses concerns of environmental racism, or the disproportionate placement of polluting industries in communities of color.

Eric Jantz, senior staff attorney with the New Mexico Environmental Law Center, a law firm that helps environmental justice communities fight industries in New Mexico, called the announcement encouraging. “I have noticed that things are starting to change over the last year [at the EPA]. It’s not dramatic or seismic changes, but there are changes.”

Over the years the EPA has faced criticism for not investigating civil rights complaints in an urgent manner, usually taking years to close an investigation. “The civil rights aspect of EPA has been historically an afterthought at best,” Jantz said. “There’s never really been aggressive enforcement.” But, he added the new office signals a greater commitment to enforcing civil rights protections.

Burwell said she sees the announcement as another stepping stone toward achieving environmental justice.

“I know that we are still in this fight, and that we’ve got a long way to go,” she said. “When you are fighting a war you win a few battles … I am so excited that the EPA has recognized the work and the sacrifice of Warren County and chose it to make this announcement and I recognize that the struggle is not over for environmental justice.”

“I wish that it had been done sooner. I’m thankful that it is being done now.”