By Antonio Ray Harvey, California Black Media

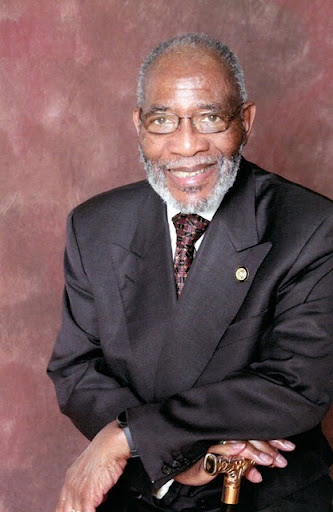

The Rev. Amos C. Brown is vice-chair and the senior member serving on the nine-member California Task Force to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African Americans.

Brown, 80, says he is “extremely pleased” with what the committee has accomplished after four meetings.

The task force held its fifth and final two-day meeting session of 2021 on Tuesday, Dec. 7 and Wednesday, Dec. 8. As written in Assembly Bill (AB) 3121, the group has until 2023 to present a set of recommendations to the state for consideration.

“The task force has been extremely focused and substantive. We have some of the best minds – people who know the history, psychology, and sociology of the pressure Black folks in this country have felt,” Brown told California Black Media.

The task force was created after Gov. Gavin Newsom signed AB 3121 into law in September 2020. California Secretary of State Shirley N. Weber authored the bill while she served in the State Assembly representing the 79th District in San Diego.

The law calls for the state to set up a task force to study slavery, Jim Crow segregation and other injustices African Americans have faced historically in California and across the United States.

The group will then recommend appropriate ways to educate the Californians about reparations and propose ways to compensate descendants of enslaved people based on the task force’s findings.

The members of the task force come from diverse professional backgrounds. So far, the panel has heard testimony from a range of experts and witnesses, including descendants and representatives of people or families the government denied justice in the past; as well as historians, economists and academics.

“We’re about balance, inclusion, and stating the case precisely so that it doesn’t face paralysis of analysis or become just another study,” Brown said. “We have had too many studies of Black folks in the past. Now is the time to show us that we are serious about being one nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.”

According to Brown, African Americans in his hometown of San Francisco, need to overcome decades of psychological damage imposed by racism, discrimination and unfair government policies, including some urban renewal programs that hurt Black families more than they helped.

On Nov. 22, Brown joined, actor Danny Glover, other local Black leaders, and members of the San Francisco Reparations Committee, to ask the city to donate the historic Fillmore Heritage Center to the African American community.

Many have referred to the Fillmore neighborhood as the “Harlem of the West” in the 1940s, Brown said. By 1945, over 30,000 Black Americans lived in the historic area.

Today, around 6% of San Francisco’s population of nearly 875,000 people are Black or mixed-race African Americans.

“San Francisco City leaders have a moral obligation to right the racist wrongs that destroyed that culture and that community and allow the Fillmore Heritage Center to live up to the full meaning of its name,” Glover said in a statement.

In 2007, the center became a venue for Jazz and Blues, reminiscent of the culture and Fillmore night clubs that attracted musical greats Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker, Billie Holiday, and others.

Last May, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors voted unanimously to appoint a 15-member African American Reparations Advisory Committee.

“That building, that land, represents the disenfranchisement, redlining of Black folks in this town, and the redevelopment agency not being fair,” Brown said. “The Fillmore, 12 blocks, itself was the hub of Black entertainment, Black culture, Black businesses and Black life. You just can’t wipe out our history or our heritage.”

Born in Jackson, Mississippi in 1941, Brown says he was delivering JET magazine when the popular weekly published graphic photos of 14-year-old Emmett Till murdered by a White racist mob in August1955 in Money, Mississippi, a rural area known for the cultivation of cotton. The lynching of Till ignited the civil rights movement.

“Emmett and I were the same age,” Brown said. “When I picked up a copy (of Jet magazine), I saw that mutilated head. It horrified me. I remember it vividly.”

Brown first arrived in the city of San Francisco in 1956 with Medgar Evers, who was a state official of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) chapter in Mississippi.

Evers brought the 15-year-old Brown to the Bay Area to attend the NAACP’s national convention where he first met Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. A year before, Brown had started the NAACP’s first youth council.

Brown later studied under King at Morehouse College in Atlanta.

In 1961, he was arrested with King at a lunch counter sit-in and joined the Freedom Riders, a group of activists who protested segregation in the South.

“In 1960, before I joined the Freedom Riders, the NAACP Youth Council actually organized the first ‘sit-down protest’ in Oklahoma City in August 1958,” Brown said “The first sit-down movement did not start in Greensboro, North Carolina. It began in Oklahoma City, Wichita (Kansas), and Louisville (Kentucky) under the auspices of the Youth Council of the NAACP.”

Brown earned a Doctor of Theology from United Theological Seminary in Ohio and a Master of Theology from Crozer Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania.

Brown has been the Pastor of Third Baptist Church of San Francisco since 1976. From 1996 to 2001, he served on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. He is president of the San Francisco Branch of the NAACP and a member of the organization’s national board of directors.

Brown said he is monitoring reparation legislation and conversations across the country to see if proposals being put forward are in sync with California’s efforts.

“What I want to accomplish is: Black people being and knowing that something was done about their pain — that can be done in the state of California,” Brown said. “Things can never be perfect, but at least collectively people of conscious and good will can stand up and say, ‘this is what we must do to right this wrong.’”