AARON MORRISON | AP

On a recent Sunday, Ernestine Alpha Gibbs returned to Vernon African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Not her body. She had left this Earth 18 years ago, at age 100. But on this day, three generations of her family brought Ernestine’s keepsakes back to this place which meant so much to her. A place that was, like their matriarch, a survivor of a long-ago atrocity.

Albums containing black-and-white photos of the grocery business that has employed generations of Gibbses. VHS cassette tapes of Ernestine reflecting on her life. Ernestine’s high school and college diplomas, displayed in not-so-well-aged leather covers.

The diplomas were a point of pride. After her community was leveled by white rioters in 1921 — after the gunfire, the arson, the pillaging — the high school sophomore temporarily fled Tulsa with her family. “I thought I would never, ever, ever come back,” she said in a 1994 home video.

But she did, and somehow found a happy ending.

“Even though the riot took away a lot, we still graduated,” she said, a smile spreading across her face. “So, we must have stayed here and we must have done all right after that.”

Not that the Gibbs family had it easy. And not that Black Tulsa ever really recovered from the devastation that took place 100 years ago, when nearly every structure in Greenwood, the fabled Black Wall Street, was flattened — aside from Vernon AME.

The Tulsa Race Massacre is just one of the starkest examples of how Black wealth has been sapped, again and again, by racism and racist violence — forcing generation after generation to start from scratch while shouldering the burdens of being Black in America.

All in the shadow of a Black paradise lost.

“Greenwood proved that if you had assets, you could accumulate wealth,” said Jim Goodwin, publisher of the Oklahoma Eagle, the local Black newspaper established in Tulsa a year after the massacre.

“It was not a matter of intelligence, that the Black man was inferior to white men. It disproved the whole idea that racial superiority was a fact of life.”

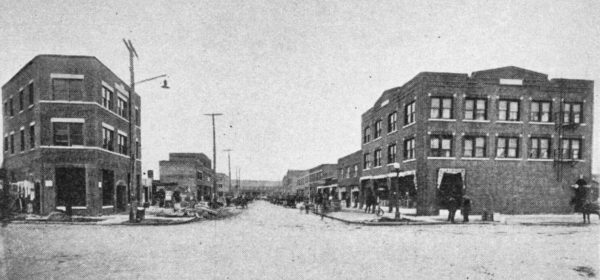

Prior to the massacre, only a couple of generations removed from slavery, unfettered Black prosperity in America was urban legend. But Tulsa’s Greenwood district was far from a myth.

Many Black residents took jobs working for families on the white side of Tulsa, and some lived in detached servant quarters on weekdays. Others were shoeshine boys, chauffeurs, doormen, bellhops or maids at high-rise hotels, banks and office towers in downtown Tulsa, where white men who amassed wealth in the oil industry were kings.

But down on Black Wall Street — derided by whites as “Little Africa” or “N——town” — Black workers spent their earnings in a bustling, booming city within a city. Black-owned grocery stores, soda fountains, cafés, barbershops, a movie theater, music venues, cigar and billiard parlors, tailors and dry cleaners, rooming houses and rental properties: Greenwood had it.

According to a 2001 report of the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921, the Greenwood district also had 15 doctors, a chiropractor, two dentists, three lawyers, a library, two schools, a hospital, and two Black publishers printing newspapers for north Tulsans.

Tensions between Tulsa’s Black and white populations inflamed when, on May 31, 1921, the white-owned Tulsa Tribune published a sensationalized report describing an alleged assault on Sarah Page, a 17-year-old white girl working as an elevator operator, by Dick Rowland, a 19-year-old Black shoeshine.

“Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in Elevator,” read the Tribune’s headline. The paper’s editor, Richard Lloyd Jones, had previously run a story extolling the Ku Klux Klan for hewing to the principle of “supremacy of the white race in social, political and governmental affairs of the nation.”

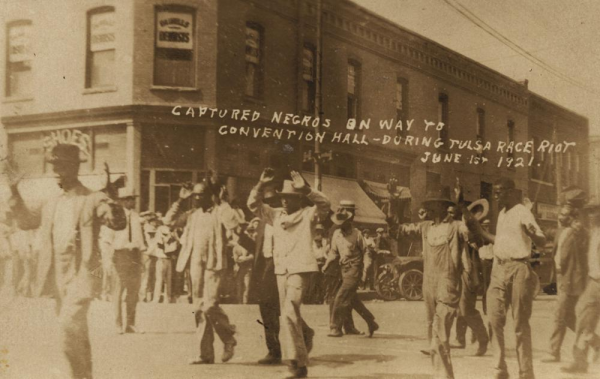

Rowland was arrested. A white mob gathered outside of the jail. Word that some in the mob intended to kidnap and lynch Rowland made it to Greenwood, where two dozen Black men had armed themselves and arrived at the jail to aid the sheriff in protecting the prisoner.

Their offer was rebuffed and they were sent away. But following a separate deadly clash between the lynch mob and the Greenwood men, white Tulsans took the sight of angry, armed Black men as evidence of an imminent Black uprising.

There were those who said that what followed was not as spontaneous as it seemed — that the mob intended to drive Black people out of the city entirely, or at least to drive them further away from the city’s white enclaves.

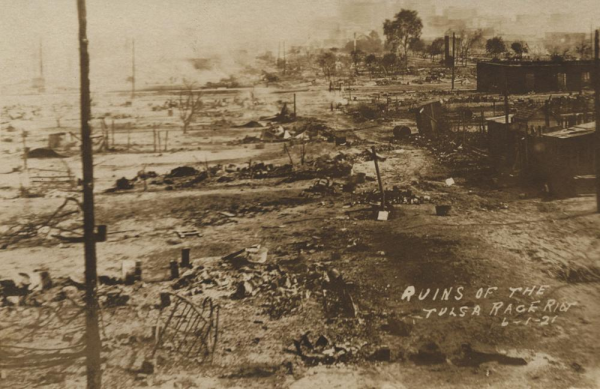

Over 18 hours, between May 31 and June 1, whites vastly outnumbering the Black militia carried out a scorched-earth campaign against Greenwood. Some witnesses claimed they saw and heard airplanes overhead firebombing and shooting at businesses, homes and people in the Black district.

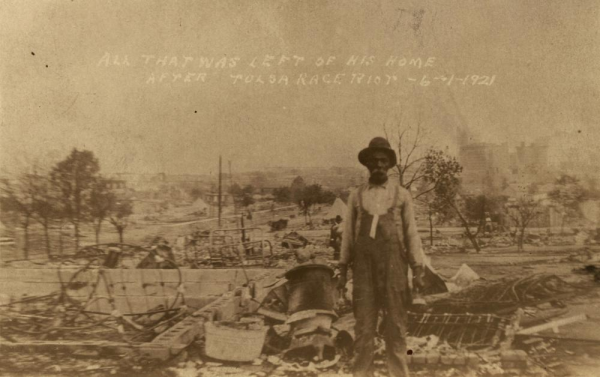

More than 35 city blocks were leveled, an estimated 191 businesses were destroyed, and roughly 10,000 Black residents were displaced from the neighborhood where they’d lived, learned, played, worked and prospered.

Although the state declared the massacre death toll to be only 36 people, most historians and experts who have studied the event estimate the death toll to be between 75 and 300. Victims were buried in unmarked graves that, to this day, are being sought for proper burial.

The toll on the Black middle class and Black merchants is clear. According to massacre survivor Mary Jones Parrish’s 1922 book, R. T. Bridgewater, a Black doctor, returned to his home to find his high-end furniture piled in the street.

“My safe had been broken open, all of the money stolen,” Bridgewater said. “I lost 17 houses that paid me an average of over $425 per month.”

Tulsa Star publisher Andrew J. Smitherman lost everything, except for the metal printing presses that didn’t melt in the fires at his newspaper’s offices. Today, some of his descendants wonder what could have been, if the mob had never destroyed the Smitherman family business.

“We’d be like the Murdochs or the Johnson family, you know, Bob Johnson who had BET,” said Raven Majia Williams, a descendant of Smitherman’s, who is writing a book about his influence on Black Democratic politics of his time.

“My great-grandfather was in a perfect position to become a media mogul,” Williams said. “Black businesses were able to exist because they could advertise in his newspaper.”

After the fires in Greenwood were extinguished, the bodies buried in unmarked mass graves, and the survivors scattered, insurance companies denied most Black victims’ loss claims totaling an estimated $1.8 million. That’s $27.3 million in today’s currency.

Monetary losses from Tulsa Race Massacre

Over the years, the effects of the massacre took different shapes. Rebuilding in Greenwood began as soon as 1922 and continued through 1925, briefly bringing back some of Black Wall Street.

Then, urban renewal in the 1950s forced many Black businesses to relocate further into north Tulsa. Next came racial desegregation that allowed Black customers to shop for goods and services beyond the Black community, financially harming the existing Black-owned business base. That was followed by economic downturns, and the construction of a noisy highway that cuts right through the middle of historic Greenwood.

Interstate 244 dissects the neighborhood like a Berlin wall. But it is easy for visitors to miss the engraved metal markers at their feet, indicating the location of a business destroyed in the massacre and whether it had ever reopened.

“H. Johnson Rooms, 314 North Greenwood, Destroyed 1921, Reopened,” reads one marker.

“I’ve read every book, every document, every court record that you can possibly think of that tells the story of what happened in 1921,” Amusan told the tour group in mid-April. “But none of them did real justice. This is sacred land, but it’s also a crime scene.”

No white person has ever been imprisoned for taking part in the massacre, and no Black survivor or descendant has been justly compensated for who and what they lost.