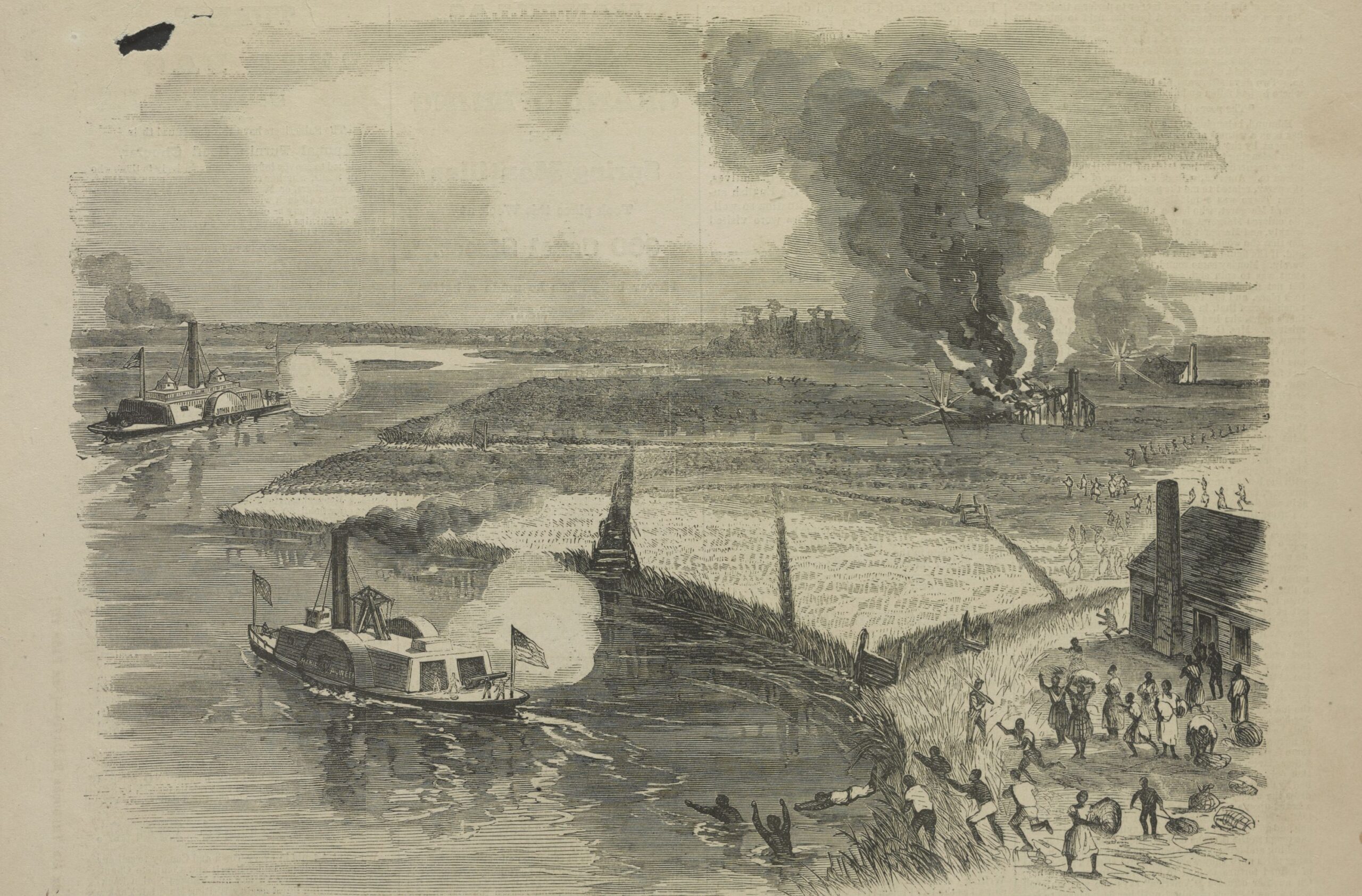

(CNN) — In the early hours of June 2, 1863, Union army gunboats idled along the banks of South Carolina’s Combahee River, waiting to give the signal to the enslaved people hiding ashore.

When the boats sounded their steam whistles, more than 700 men, women and children fled the plantations along the river to race toward freedom, in an operation that came to be known as the Combahee Ferry Raid.

Harriet Tubman led the secret operation, alongside more than 100 Black Union soldiers – making her the first woman in US history to lead a major military operation.

This year marks the 161st anniversary of the raid, and the Tabernacle Baptist Church – the first Black Baptist church in Beaufort, South Carolina – unveiled a monument commemorating the pivotal military operation that reshaped the state’s Lowcountry.

Ninety-year-old sculptor and engineer Ed Dwight told CNN he spent eight years crafting the statue. The 14-foot bronze monument features a steamboat, Tubman, two Union soldiers and about a dozen enslaved people seeking freedom.

“I could just put a statue of her [Tubman] standing there with none of the kids and other slaves featured … then put a plaque there to tell the story,” Dwight said. “But I had to put that river boat and put this whole thing in context.”

Dwight dedicated the early part of his career to the Air Force and became the first Black astronaut candidate in US history, but he was denied the opportunity to join NASA.

He later decided to focus on the arts, creating statues of historical African American figures including Frederick Douglass and Barack Obama. Last month, he completed his first trip to space with Blue Origin.

Dwight told CNN he didn’t come to appreciate the impact historical figures like Tubman had on the nation’s history until much later in life because he attended all-White private Catholic schools, where African American history wasn’t taught to students.

He said it wasn’t until he was gifted a stack of history books that he learned about the important figures in Black history.

“Harriet Tubman stuck from the very beginning because she was the first name that I could hang on to,” Dwight said. “Here’s this woman, barely 5 feet tall, running around against the odds doing all these incredible things,” he added. “I became an early fan of hers and I’ve done several memorials of her.”

Rev. Kenneth Hodges, the pastor of Tabernacle Baptist Church, said it was only right for the church to honor Tubman and other historical figures who played a significant role in Beaufort’s history.

“Most people don’t know about the raid,” Hodges said of the significance of the statue. “Harriet Tubman is standing on top of the monument and she’s reaching back to the generations yet unborn to come along.”

Combahee River Raid

Tubman is widely known for escaping slavery and becoming one of the most prominent conductors of the Underground Railroad – successfully rescuing about 70 enslaved people during more than a dozen trips, according to the National Park Service.

When Tubman first traveled to Beaufort, South Carolina, in 1862, there were nearly 200 plantations that held approximately 10,000 enslaved people, according to the National Park Service.

Tubman served as a volunteer for the Union Army, working as an informant behind enemy lines in the South, as well as a nurse, laundress and cook before eventually becoming a spy and scout, according to the National Museum of African American History.

Just before midnight on June 1, 1863 – around two years into the Civil War – Tubman and Col. James Montgomery of the Union Army set sail up the Combahee River, leading three military gunboats of about 150 Black Union soldiers.

“They knew they had to do it under the cover of darkness,” said Karen Hill, CEO of the Harriet Tubman Home, the nonprofit that manages the Harriet Tubman National Historical Park.

The ships reached the banks of South Carolina’s Lowcountry plantations early the next morning where more than 700 enslaved people hid in the shadows, waiting for Tubman and the soldiers to sound the ships’ whistles.

“When she gave the signal, they just came out from the rice fields to the water,” Hill told CNN. Hundreds of men, women, and children escaped to the military ships carrying all their belongings.

“That was the largest raid emancipating [enslaved] people in the United States,” Hill said.

Faith and Juneteenth

The Tabernacle Baptist Church unveiled the statue and commemorated Tubman’s heroic raid with song, prayer, and speeches during a ceremony earlier this month. Rev. Hodges said more than 500 people attended, including Ernestine Wyatt, Tubman’s great-great-great grandniece.

“When I allow myself to think about it, I begin to cry because I think about how hard life was,” Wyatt told CNN. “She had liberated herself, but it didn’t mean as much to her as it could have because she didn’t have her family there with her.”

Wyatt said Tubman’s determination to rescue her enslaved loved ones – as well as strangers – despite the life-threatening risks, is a prime example of her unwavering faith in God.

“I would have to say that a lot of that [faith] transpired from Aunt Harriet to my great grandmother, to my grandmother, to my mother, and then to me,” Wyatt said.

“That part of her is in my DNA.”

Faith was a reoccurring theme throughout the commemoration ceremony.

“Many people have sown into our present and our future, and it’s important for us to remember them in a meaningful way,” Hodges told CNN. “We are highlighting the struggle, their faith, their commitment, and their service through the years.”

Hodges, a former South Carolina state representative, introduced a bill in 2006 to name a future bridge that would span the Combahee River, the Harriet Tubman Bridge. The bridge now stretches across the blackwater river between Beaufort and Colleton counties.

Dwight said faith was also a key concept behind the vision for the Tubman sculpture.

“My propensity is to tell larger stories to have people just not look at her and walk away,” he said. “But to provoke thought … and to walk away with a picture in their head about what it was like (then) compared to what it is today.”

While abolitionists worked to end slavery in the United States, many didn’t expect to see it come to fruition during their time on Earth – except Tubman, according to her great-great-great grandniece.

Tubman, she said, would often share that God revealed that her “people are free” in a dream and that the emancipation of enslaved people was already done.

“Prior to the war starting she had a vision,” Wyatt said.

Two years after the Combahee Ferry Raid and President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, the last enslaved people were set free in Texas on June 19, 1865 – a day celebrated as Juneteenth.

Juneteenth became a national holiday in 2021 to commemorate the abolishment of slavery.

Tubman died of pneumonia on March 10, 1913, at 91 years old, according to the National Women’s History Museum. Surrounded by loved ones, her final words were documented as “I go away to prepare a place for you,” a reference to John 14:3 in the Bible, according to Kate Clifford Larson, author of “Bound for the Promised Land: Harriet Tubman, Portrait of an American Hero.”

“Aunt Harriet did her part,” Wyatt said. “Now we have to do things to help ourselves heal.”

And the best way to do that, she said, is to celebrate freedom.

“Do something loving for another person to celebrate that freedom that was given.”

The-CNN-Wire