By Macy Meinhardt, Voice & Viewpoint Staff Writer

“The problem with a pretextual traffic stop is that it is a search and seizure which cannot be constitutionally justified for its true reason, but only for some other reason,” State V. Ladson, 1999.

The weight of generational trauma and mistrust between racial minorities and local law enforcement was palpable as the community gathered for a hearing on pretextual stops in San Diego. Held by the City’s Police Practices Commission at the George L. Stevens Center, residents recounted a troubled history of traffic stops and police encounters; reflecting a need to reform San Diego Police Department policy.

A pretextual stop occurs when police enact a minor traffic stop to investigate a crime, rather than enforce a traffic code. Essentially, they allow police to pull people over on the basis of a “hunch” which many claim are fueled by racial stereotypes.

“The notion that an officer can create any mental conditions within himself to determine his justification for stopping a person who— more often than not— is going to be Black and brown and or from a marginalized community. That alone is the foundation of a problem,” said resident Samantha Judkins.

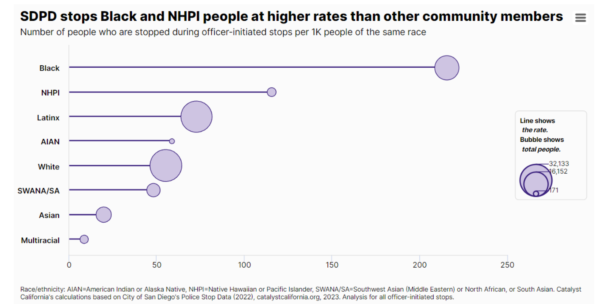

Black individuals are stopped 132% more frequently than expected given their 5% proportion of the California population, according to data collected by the Racial Identity Profiling Advisory Board. In San Diego, Black individuals comprise 6% of the city’s population and were stopped 32% of the time.

It is widely argued that law enforcement abuses the use of traffic stops, especially over minor infractions—such as a broken taillight—as a way to instigate a search. Claims that these searches violate the fourth amendment right, which frees citizens from an unreasonable search, are also made. In 1996 however, the United States Supreme Court affirmed the legality of pretext stops. Through the ruling of Wren V. United States, the court held:

“A traffic stop is reasonable under the Fourth Amendment if a police officer has probable cause to believe that a traffic violation has occurred, even if the stop is a pretext for the investigation of a more serious offense.”

In the two decades since the decision, the concept still remains a contentious issue within the community.

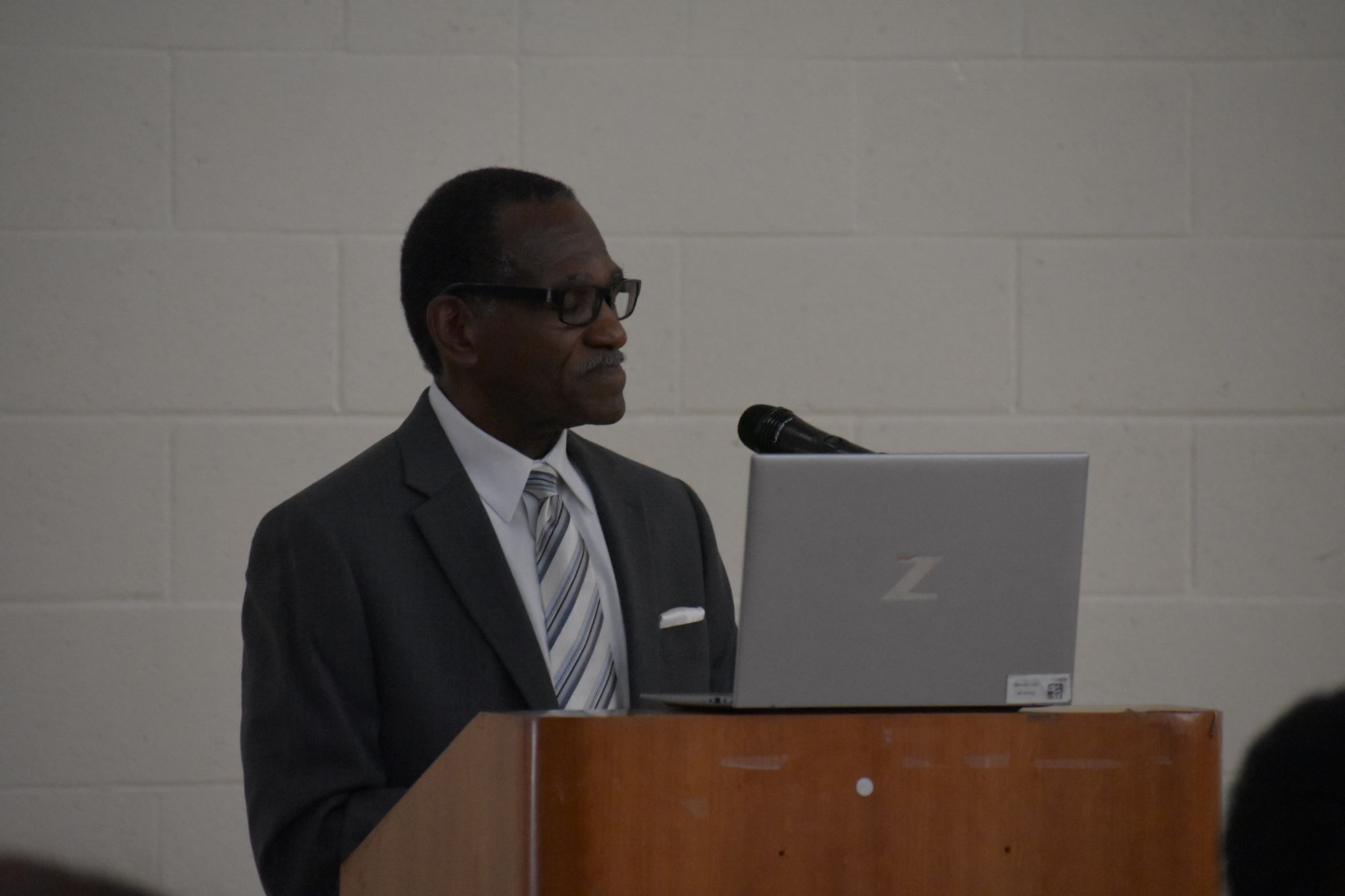

In introducing the topic of reforming how the SDPD conducts pretextual stops, CPP Counsel Duane Bennett emphasized, “This is not about letting crime go free,” Instead, it’s a community call for systemic change and greater accountability from law enforcement in their interactions with communities of color.

Bennett’s preface is connected to the common criticism of police reform. With opponents such as the San Diego Police Union claiming the ideology reflects an attempt to abolish law and order completely.

“Extreme activists who failed to defund the police in San Diego have taken this act up as their new attempt at dismantling, demoralizing, AND abolishing the police department,” said Police Officer Association President Jared Wilson.

Yet, Bennett maintains:

“Unless you subscribe to the racist, discriminatory notion that the only people that are committing crimes in the United states are Black and Brown, you cannot interpret anything I say to infer that it is about allowing crime to run around,” said Bennett.

Other police commissions in cities such as Los Angeles have already begun to enact changes. In March 2022, Los Angeles Police Department implemented a new policy aimed at reducing the use of pretext stops by: limiting the circumstances in which traffic stops can be made by officers, and requiring officers to state a reason to believe the person stopped has committed a serious crime.

According to data collected by RIPA on the effectiveness of the new policy shows that between 2021 and 2022, pretextual search stops decreased by 15% overall and 3% among Black individuals.

In a further effort to address pretext stops across the state, Assembly Bill 2773 took place in Jan. 2024 which requires officers to announce the reasons for vehicle stops and police agencies to track whether officers who stop drivers are complying with the law.

Another area discussed was how the majority of stops occur in certain regional areas “known” for high-crime, such as Southeastern San Diego. This makes up a practice known as gang profiling. Upon stopping an individual, officers will interrogate an individual and document personal information on a Field Interview Card that is put into a gang member database. The collected information may include the pers

on’s name, date of birth, race, gender, nicknames, family and friends’ names, residence, community, photos, tattoo descriptions, clothing at the time of the stop, vehicles, and any suspected gang affiliation noted by the officer.

In 2022, the SDPD conducted 1,100 stops leading to field interviews in the predominantly Black and less affluent Southeastern Division, compared to just 171 in the more affluent, predominantly White Northwestern Division.

The impacts of gang profiling on the Black and Latino community are devastating, and District 4 resident Nicholas Hoskins knows this story all too well.

“I don’t know about you, but I have never had a positive experience with the SDPD—matter of fact my last encounter was one of the most traumatic,” Hoskins recalled.

The 31-year-old Black man recently spent eight years in prison on a false conviction for conspiracy to commit murder before the California Supreme Court overturned his conviction for lack of evidence and set him free. After his release in 2023, Hoskins shared how he has since been stopped four times in the last year, with the last stop resulting in officers assaulting him and his property after he refused to get out of the car and consent to a search.

Personally videoing the whole encounter, officers refused to give a reason as to why they wanted to search Hoskins’ car.

“What is the probable cause for a search?” Hoskins asked.

“I am going to break your window if you continue to play this game,” the officer replied.

After refusing consent, officers smashed his window, spewing glass all over him and eventually forced him out of the car and handcuffed him. Police searched the car and found no weapons but transported him to the police department before releasing him with a citation for resisting arrest.

Hoskins reportedly paid $1,000 to get his car back from impound and get his window fixed.

Hoskins narrative is reflective of an entire community that showed up in large numbers for the hearing on police pretext stops. As a culmination of personal testimony, research, and data gathering, CPP are looking into a variety of recommendations to mitigate the occurrence of racialized pretext stops. Recommendations the CPP are looking into include:

- Acknowledge the disparate impact pretext searches have on People of Color

- Revise policy to remove vagueness and ambiguity regarding use o race or ethnicity in stops, detentions and arrests

- Strict compliance with policy regarding training and external experts to identity inequities and disparate patterns

- More scrutiny regarding usage of consent searches where safety concerns are not an issue, and for stops related to equipment violations

- Improve data transparency, and compliance with the Racial Identity Profiling Act

What do you think of racially motivated pretext stops? We want to hear from you, email us your input at [email protected]