By Emma Fox, Contributing Writer

Just a few nights before their lives changed forever, Ricardo Mejia and his fiancée Camila took an evening stroll through their neighborhood in Altadena, California. Camila admires the beautiful flowers in her neighbor’s yards and takes mental notes as she plans out her garden.

Now, a few weeks after Los Angeles’ Eaton Fire burned down the very same block, Camila thinks back to that walk. She thinks of those gardens and all the neighbors who planted them, and who are going through the struggle she and her fiancé are experiencing now.

Camila notes that despite the fire, their financial commitments remain, and their future plans have been upended. She says, “We were just planning on making space in that house, building on so we can all live together.” Ricardo’s brother, sister-in-law, and their kids also lived with the couple.

Ricardo and Camila are one of the hundreds of families affected by Los Angeles’ Eaton Fire and each one of them is now grieving not just their physical belongings but the plans they’d made. The image of the future they had spent so much time painting became murky the night of the fire.

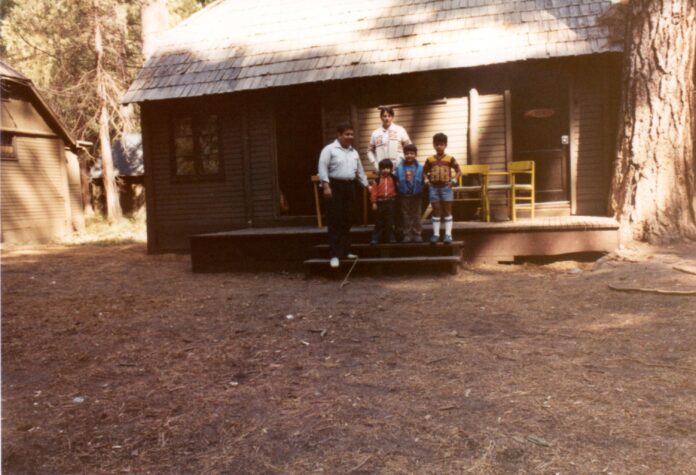

Ricardo’s family is as Altadenan as they come. The Mejias have lived in the area since it was still part of Mexico. Ricardo’s great-grandfather moved up to the area circa 1914.

“When I met Ricardo, he mentioned his family reunions that they do every year. I always thought that sounded so amazing because I have a large family as well. You know, a lot of Latinos, we come from a big family, but we don’t do an official, yearly reunion,” Camila says. Each year, the Mejia family reunites in Eaton-Blanche Park to celebrate another year well spent together in Altadena.

Ricardo bought his house just minutes from the house he grew up in. With cousins living all over the area, Camila says her husband’s “family roots are there in Altadena. “When I started spending time in the neighborhood, just on his block alone, I noticed that the people there had been in their homes for generations.” She continues, “It’s rare to have so many minorities owning homes and businesses and in the last couple of days, we’ve been talking about how this affected the makeup of the town.”

Ricardo says of his town: “You appreciate all those landmarks in Altadena that you grew up with. For instance, my chiropractor’s office is on Lake Avenue, and the set of buildings that were there were very unique. I remember being in junior high school… I loved to collect baseball cards, and my chiropractor’s office is right next to the store for baseball cards.”

Camila responds, realizing that Ricardo had an appointment with that same chiropractor the Friday after the fire. Ricardo, she says, wouldn’t make that appointment now. By that Friday, his chiropractor’s office had burned down.

Across the street, Eliot Middle School, which he would walk from in pursuit of those baseball cards, was gone too. In fact, every school he went to before college burned down, even his preschool.

Most Angelenos are used to traveling from city to city for their doctor’s appointments, social engagements, and work obligations. L.A. is so expansive and so accessible (by car) that it is common for people to have their life spread out.

Altadena, between Pasadena and the San Gabriel mountains, is an increasingly rare town. A person’s dentist, chiropractor, and gym are all within minutes of each other. Most residents have spent their lives loyally frequenting the same establishments run by other community members. They never thought they would need to look beyond the town for any of their basic needs.

Ricardo refers to his father as ‘the family archivist,’ he says. “This is his passion, archiving our family history with his brothers.” Ricardo’s Uncle Alejandro Mejia wrote a book about Ricardo’s great-grandfather, Gregorio.

Gregorio was interviewed on a local radio station in the 80s or 90s, Ricardo recalls. In the interview, he talks about how he made his living doing odd jobs. Ricardo says, “When [his great-grandfather] was raising his kids, he wanted to make sure that they went to school so that they could have careers, not just jobs.”

Back in Gregorio’s era, they called Altadena, “Chihuahuita” as many of its inhabitants hailed from Chihuahua, Mexico. He described the humble beginnings of the town, with its small wooden houses, and residents who made a modest living.

Camila says the settlers took care of their community and grew it, and then a hundred years later “something like this happens, and you start thinking… generations of their families did the groundwork there. Now what’s gonna happen? Are people going to come in and take it? It’s really upsetting just to see a lot of people hurting right now because they’re losing a lot more than a home. It’s their family, it’s their memories,” says Camila.

Like many displaced Altadena families, Camila and Ricardo are deeply concerned about losing not just their home, but the property it stood on. For some, selling their land feels like the only way out as they’re overwhelmed by financial pressures. The decision is only made more stressful by the family roots sown into the now-charred earth.

Ricardo says that it’s easy for his message to his neighbors to be, “Don’t leave,” but he knows that would ignore the reality that many families don’t have the luxury of choice.

He continues, “I’m learning that even if the insurance pays out the maximum amount to rebuild, that money goes to the mortgage company, and they’re gonna zero out the account. So, we’re gonna get what’s left over once the entire mortgage is paid off to rebuild. Which…that’s not gonna be enough. And, there’s some families that own their homes outright. Now they have to take out a construction loan, and now they have a new mortgage.”

Camila expresses her concern over taking on the arduous process of rebuilding just to live with the possibility that it all gets ripped away again. She describes reading articles about climate change and feeling inundated with information. She says she’s left wondering, “Is it safe? And, if we do rebuild, what is the state going to put in place to make sure people’s homes are insured now? Or are they just going to allow people to build, and then not guarantee insurance coverage?”

“It starts changing the way you see your life now,” Camila says, “We have his bag. It’s still packed. That’s the only thing he has because he really was expecting to go back. We didn’t realize that this was going to be… what it is.”

They have bins of their belongings and emergency supplies in the living room of the house they are staying at, “in case something happens, we just pop it in the car, and we’re ready to go,” Camila says.

Ricardo describes what it felt like to watch the fire burn from where he evacuated, “right now, we’re not too far from the foothills of the mountains over here. So, when these winds were still blowing, there was a huge worry in this house that they’re gonna shut off our power, and we’re like, are we gonna be chased away from this place?”

Ricardo says he had gotten used to fires in the mountains and never paid them much mind because he had faith in the firefighters who had saved the day again and again over the years. On the night the Eaton Fire reached Altadena, the nation realized even its best-funded state for combating wildfires was no match for the winds up to 59 mph and what reporters on the ground called ‘fire tornadoes.’

There are so many difficult obstacles that Ricardo and Camila must face now, including the possibility of changing the timeline for their engagement. Donate and help Ricardo get his family back on their feet and provide them more agency to decide what comes next. Visit: https://www.gofundme.com/f/help-ricardo-mejia-after-eaton-fire