(CNN) — On a Friday in June, Frances Thompson swore an oath before a congressional committee and began to testify about what she’d experienced during a race riot in Memphis one month earlier.

She told the committee how seven White men, including two police officers, forced their way into her home and stole her money and all her meager belongings before sexually assaulting her and her teenage housemate.

In sharing her harrowing experience, Thompson quietly made history. She is believed to be the first Black transgender woman to testify before Congress.

Thompson’s testimony in 1866 came at a critical time, as the nation weighed whether to expand equal constitutional protections to newly freed Black Americans. But it also came at a great personal cost – a decade after her landmark testimony, Thompson was cruelly outed, arrested for cross-dressing and forced to work in an all-male chain gang.

Historians and advocates tell CNN they draw parallels between all that Thompson experienced as a Black trans woman and today’s anti-transgender political climate after President Donald Trump signed numerous executive orders targeting trans American minors’ right to access medical treatment and participate in school sports teams aligned with their gender identities..

Bryanna Jenkins, policy director at the Lavender Rights Project, which works to address what it calls a “crisis of violence” against the Black trans community, said in order to understand how to defend the civil rights of transgender Americans today, we need to examine the history and experiences of trailblazers like Thompson.

“If we’re going to strategize and be honest about where we have to go,” she said, “we have to look back.”

‘Kill the last damned one:’ The Memphis Race Massacre

Exactly one year after the end of the Civil War, on April 9, 1866, Congress overrode President Andrew Johnson’s veto to enact the nation’s first civil rights law.

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 declared freed Black Americans were citizens entitled to “full and equal benefit of all laws … as is enjoyed by white citizens.”

Then the massacres began.

On May 1, 1866, a White mob laid siege to the nascent Black community that had begun to thrive in Memphis, Tennessee.

Despite the end of the war, many White people violently resisted the federal push for formerly enslaved Black Americans to have equal rights. In Memphis, tensions often ran high between Black Union soldiers and the city’s poorer White residents.

After a skirmish between the soldiers and police, a local politician stoked a White mob into a frenzy by telling the men to “go ahead and kill the last damned one of the n***er race,” according to the 1866 congressional investigation into the massacre.

“They are free, indeed,” the politician said, “but … we will kill and drive the last one of them out of the city.”

For three days, the rioters – which included the city’s police – terrorized Black residents, indiscriminately murdering, raping and robbing people, according to the 1866 report.

No one was spared. The mob attacked the sick and elderly and raped multiple women, according to the report. Rachel Hatcher, a 16-year-old girl, was shot and killed and her body burned in a fire. The rioters then set fire to a home with women and children inside and shot them as they ran out.

In the end, the White mob killed more than 40 people, injured dozens and destroyed countless homes, churches and businesses, according to the report.

The attack would become known as the Memphis Race Massacre.

‘Not that sort of women:’ Frances Thompson testifies

In the days that followed, Congress dispatched federal agents and members of the Freedman’s Bureau – which had been founded to help the formerly enslaved transition into citizenship – to interview survivors and document what had occurred.

Frances Thompson was “one of many women who got up that morning and walked to the congressional hearing and told her story,” historian Hannah Rosen said.

Rosen’s book, “Terror in the Heart of Freedom,” details how White men weaponized sexual violence against Black women after the Civil War – and highlights the bravery of women like Thompson who shared their experiences.

Investigators noted that Thompson used crutches and described herself as a “cripple” who had “cancer in (her) foot.” On the first night of the massacre, Thompson said the White men – including two police officers – entered her home and demanded that she and her 16-year-old housemate, Lucy Smith, make them dinner.

“When they had eaten supper, they said they wanted some woman to sleep with. I said we were not that sort of women, and they must go,” Thompson testified. “They drew their pistols and said they would shoot us and fire the house if we did not let them have their way with us.”

Thompson said she was assaulted and beaten so badly she remained in bed for days and was sick for two weeks. Lucy Smith, who was also attacked and assaulted, testified that she “thought they had killed me.”

Newspapers published excerpts from the House report. Rosen said the brutality of the massacre, combined with the testimony of Thompson and the other women who were assaulted, horrified the nation.

Then, later that summer, another White mob descended on a Black political rally in New Orleans, killing 34 Black residents and injuring more than 100 people.

At the time, states were weighing whether to ratify the 14th Amendment, and the combined horrors of the back-to-back race massacres underscored the need for constitutional protections to ensure Black Americans had equal rights.

The text of the 14th Amendment borrowed heavily from the language of the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which declared all people born in the United States, except for Native Americans who did not pay taxes, to be US citizens, regardless of their race or “previous condition of slavery or involuntary servitude.”

The law’s language around “full and equal benefit of the law” was also adapted into the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause.

Rosen credits the bravery of Thompson and the other women who testified with helping to shift the national sentiment around the 14th Amendment.

“Her impact isn’t direct, but she was part of the large numbers of people in Memphis … who showed enormous courage showing up to tell their story to congressional leaders who were not necessarily sympathetic,” Rosen said.

“We can only assume she did that because they hoped it would have an impact, and they wanted their stories recorded, and they wanted the world to change.”

Despite her bravery, Thompson was later forcibly outed as a transgender woman – and her life would ultimately end in tragedy.

A decade later, Thompson is outed and forced to work in chains

Not much is known about Thompson’s life until a decade after the massacre, when her name once again began to appear in newspapers.

A decade after the end of the Civil War, the gains made during Reconstruction had already started to wane. Many Black residents had fled Memphis after the massacre, and the state took over the Memphis police department, Rosen said, because the officers “were seen as out-of-control ruffians … who had obviously been a key source of the violence.”

In 1876, Thompson was still living in South Memphis when rumors began circulating that she was “cross-dressing,” a violation of a local ordinance.

She was arrested and conservative newspapers – which had been instrumental in sowing discord before the massacres – reported that Thompson had been subjected to a medical exam and was “pronounced a member of the male sex.”

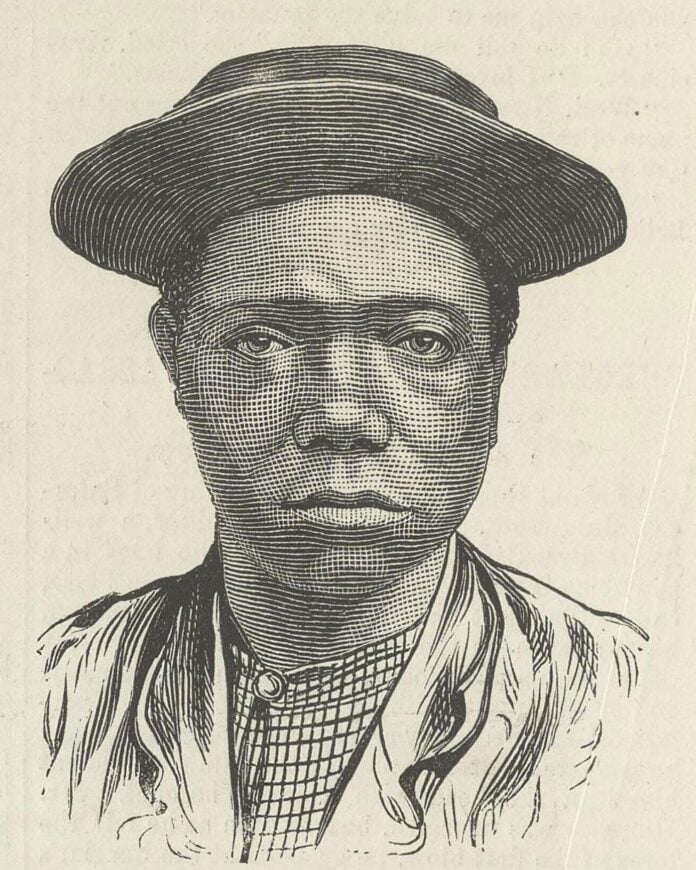

Multiple articles used Thompson’s identity to try to undermine her testimony to Congress about the Memphis Massacre. But she remained defiant – even as officers forced her to take mugshots in both men’s and women’s clothes.

She told police and local reporters that she’d lived her entire life as a woman and believed she was “of double sex.” Still, the city’s recorder fined Thompson $50 – the equivalent of around $1,000 today – and when she couldn’t pay, she was forced to work off the debt on an all-male chain gang.

Thompson was paraded through the city and humiliated as she worked off her fine. After being released from prison, Rosen said Thompson’s neighbors went to check on her and found she was ill.

They took her to a local hospital, where she later died.

The historian said in many ways, 160 years later, the country appears to be echoing the same backlash that occurred after Black Americans made modest gains towards equality following Reconstruction – and vulnerable people, like trans Americans, are once again bearing the brunt.

“History is repeating itself,” Rosen said, adding that she sees parallels in the “vilification of Black trans women in order to denigrate one’s political opponents,” and what Thompson experienced.

Like the resistance to Reconstruction, Rosen said she believes the backlash we’re witnessing today is “a reaction to the very brief window of commitment to racial equality” that followed the 2020 murder of George Floyd.

But if Thompson’s life story proves anything, Bryanna Jenkins said, it’s that trans people always have and will continue to be at the forefront of the push for civil rights in the United States.

“Black trans women and Black trans folks, we’ve always been here, we’ve always contributed,” Jenkins said.

The-CNN-Wire