SAVANNAH, Ga. (AP) — Three white men serving prison sentences in the 2020 killing of Ahmaud Arbery are asking an appeals court to throw out their federal hate crime convictions, with two of them arguing their histories of making racist comments don’t prove they targeted Arbery because he was Black.

“Every crime committed against an African American by a man who has used racist language in the past is not a hate crime,” defense attorney Pete Theodocion said in an appellate brief written on behalf of defendant William “Roddie” Bryan.

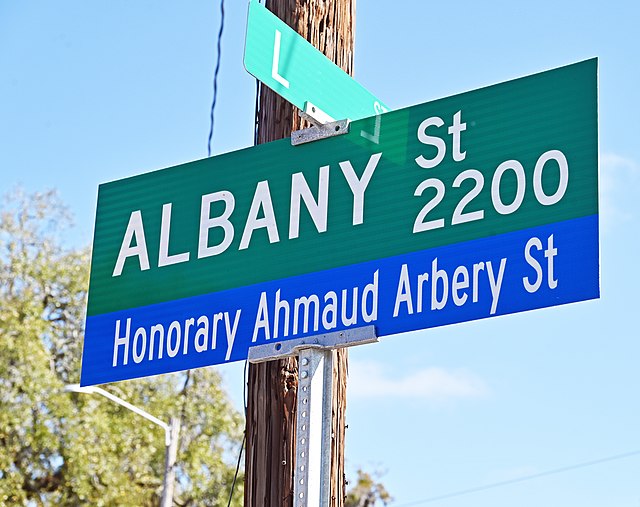

Arbery, 25, was chased by pickup trucks and fatally shot in the streets of a Georgia subdivision outside the port city of Brunswick on Feb. 23, 2020. His killing sparked a national outcry when cellphone video Bryan recorded of the shooting leaked online more than two months later.

Greg McMichael and his son, Travis McMichael, armed themselves with guns and pursued Arbery after he was spotted running past their home. Bryan joined the chase in his own truck and recorded Travis McMichael shooting Arbery at close range with a shotgun.

All three men were sentenced to life in prison after a jury convicted them of murder in a Georgia state court in 2021. The following year, they stood trial again in U.S. District Court and were found guilty of committing federal hate crimes in Arbery’s death. That jury was shown roughly two dozen racist text messages and social media posts by the McMichaels and Bryan.

They all filed legal briefs in their federal appeals March 3 with the 11th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals in Atlanta. Attorneys for Bryan and Greg McMichael say their hate crime convictions should be overturned because the evidence shows they pursued Arbery thinking he was a criminal, not because of his race.

Greg McMichael initiated the chase when Arbery ran past his home because he recognized the young Black man from security camera videos that in prior months showed Arbery entering a neighboring home under construction. None of the videos showed him stealing, and Arbery was unarmed and had no stolen property when he was killed.

Arbery’s race was “a fact of no greater import to Gregory McMichael’s calculus than Mr. Arbery’s biological sex, the shorts he was wearing, his hairstyle, or his tattoos,” wrote Greg McMichael’s attorney, A.J. Balbo. He said there would have been no chase had the runner been a Black woman.

Bryan didn’t know the McMichaels and had never seen the security camera videos. Still, his attorney said that Bryan “had every right to assume” Arbery was likely a criminal after seeing him run by with the McMichaels in pursuit and ordering Arbery to stop.

“Arbery never called out for help or gave any signs that he was the victim of an unprovoked attack,” Theodocion wrote on Bryan’s behalf.

Travis McMichael’s appeal makes no effort to challenge whether racism motivated Arbery’s killing. Instead, his attorney argues a technicality, saying prosecutors failed to prove that Arbery was chased and killed on public streets — as stated in the indictment used to charge the three men.

Defense Attorney Amy Lee Copeland says documents show that Glynn County officials declined to take over responsibility for the streets of Satilla Shores from a private developer when the subdivision was dedicated in 1958. She argued there’s no record that the county ever changed its mind.

Defense attorneys made the same arguments challenging racial motives and whether the streets were public during the federal trial in February 2021.

Prosecutors argued at the trial that the McMichaels and Bryan chased and shot Arbery out of “pent-up racial anger.”

Bryan had used racist slurs in text messages saying he was upset that his daughter was dating a Black man. A witness testified Greg McMichael had angrily remarked on the 2015 death of civil rights activist Julian Bond: “All those Blacks are nothing but trouble.” In 2018, Travis McMichael commented on a Facebook video of a Black man playing a prank on a white person: “I’d kill that f—-ing n—-r.”

On the question of whether the streets were public, prosecutors showed 101 service tickets for work the county performed in the neighborhood, mostly dealing with ditches and drainage. Copeland argued nothing showed the county paving or maintaining the streets except in relation to drainage repairs.

The U.S. Justice Department, which prosecuted the hate crimes case, has 30 days to file legal briefs in response to the hate crime appeals. Spokespersons for U.S. Attorney Jill Steinberg, the federal prosecutor for Georgia’s Southern District, and for the Justice Department in Washington declined comment Friday.

The 11th Circuit has not set a date to hear oral arguments in the hate crime appeals. Both McMichaels received life prison sentences in the federal case, while Bryan was sentenced to 35 years in prison. Also pending are appeals by all three men of their murder convictions in Glynn County Superior Court.