By Avis Thomas-Lester, Urban News Service

Doris Proctor remembers her fear 33 years ago as she sat behind her 17-year-old son, Terrance, as he was sentenced for participating in several armed robberies. Bernice Stewart, her mother and Terrance’s grandmother, sat with her. “I just kept praying,” said Doris Proctor, 68, of Grand Prairie, Texas.

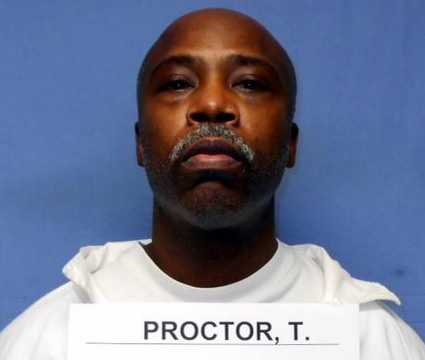

“My mother was praying. We were hoping that the judge would have mercy.” Terrance Proctor has been imprisoned in the Arkansas Department of Correction since he received 200 years plus life “at hard labor” on January 15, 1983 – two weeks before he turned 18 years old.The judge called Proctor a public threat. His supporters call his sentence excessive because he never committed physical violence against any of the robbery victims.

Proctor was not sentenced to life without parole, but the length of his prison term means he likely will spend the rest of his life behind bars unless he successfully appeals his release. His chances are slim because Arkansas administrators grant release to few inmates. The Arkansas parole board has recommended Proctor’s freedom four times, but governors have balked, records show. Like many offenders, Proctor has been imprisoned for more than three decades for juvenile crimes that did not involve assault, rape, molestation or murder, experts said. In some jurisdictions, offenders have done that much time for property crimes.

It could not be determined how many inmates are serving lengthy sentences for juvenile offenses. However, among 159,000 people serving life sentences in 2012, 7,862 were juveniles when sentenced to life, according to the Sentencing Project in Washington, D.C. Another 2,498 were minors when sentenced to life without parole.

“The next frontier in this work is to try to get legislators who make sentencing laws and judges who apply those laws to understand that juveniles should have the opportunity to be released within a reasonable amount of time,” said Rhonda Brownstein, legal director of the Southern Poverty Law Center in Montgomery, Alabama.

Proctor was charged in late 1982 with armed holdups at a high school custodian’s office, a uniform shop, a jeans store, a cab company and several gas stations. He drove the getaway car in a purse snatching. Proctor was involved in a robbery in which shots were fired at a car pursuing him and his accomplice, records show. He said his accomplice fired to flatten the vehicle’s tires to disable it. None of his other charges involved a weapon being fired.

Proctor told Urban News Service that he pleaded guilty to 10 counts of aggravated robbery because he was remorseful, though he didn’t commit some of these offenses. The Proctors said Terrance’s lawyer told them the judge would be lenient if he admitted guilt.

Doris Proctor, a nurse, reminisced about her son’s life as she sat in court that fateful morning. She had divorced his father and raised “Terry” and his sister, Kim, with the help of her parents and nine siblings.

Problems started when Terrance reached adolescence. She took him to counseling. He refused to take ADHD medication because of its side effects. Doris learned of Terrance’s November 1982 arrest from a friend who saw police detain him.

“There are potentially 10 life sentences here,” Judge Floyd J. Lofton told Proctor, according to a court transcript. “I don’t think there’s much doubt about it, Mr. Proctor, you’re going to spend the rest of your life in the Department of Correction. Do you understand that?”

“Yes, sir,” Proctor said, not understanding at all. He and his mother still believed that his lawyer would arrange a deal with the court.

“And you’re pleading guilty?” Lofton asked.

“Yes, sir.”

“How old are you?” Lofton asked.

“Seventeen,” Proctor said.

Doris Proctor asked Lofton to consider her son’s psychiatric problems, drug use and abusive father. Proctor admitted guilt. However, Lofton was not moved.

“Mr. Proctor, it is my intention that when you get out of the penitentiary you [will] be an old man,” Lofton said. “My intention is to keep you there for most of the rest of your life.”

Doris Proctor is still praying for her son – that a lawyer will come forth to help him, that he will be safe. She still has nightmares about him being stabbed in prison several years ago. She thinks his debt to society has been paid.

“My greatest hope is that I stay here long enough that I see him live as a free man,” she said. “I pray that he will have a chance to experience some of his life outside of prison.”