Members of the California Citizens Redistricting Commission defended their months of sometimes chaotic work Monday, December 27, as they handed off the completed maps that, barring successful court challenges, will govern congressional and legislative elections for the next 10 years.

By Don Thompson, Associated Press

“It was messy. And that’s the beauty of democracy,” said commission chairwoman Isra Ahmad.

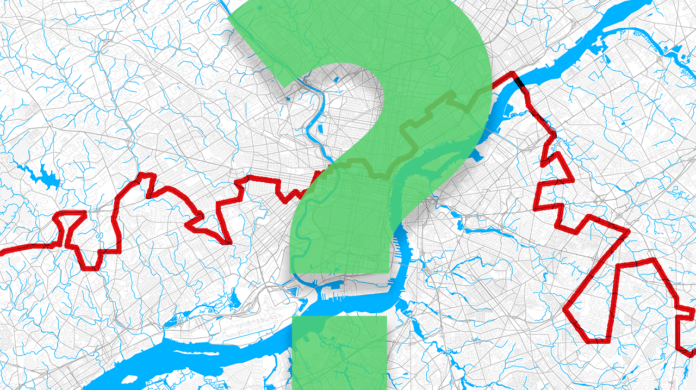

The maps they formally presented to California’s top elections official, Secretary of State Shirley Weber, form new jigsaw puzzles for 52 congressional districts, 40 state Senate districts, 80 Assembly districts and four Board of Equalization districts.

That’s one short of the 53 congressional districts that existed under the previous maps because the population in other states is growing faster, a development with national implications.

The maps reflect California’s growing Latino population.

Twenty-two of the 80 Assembly districts have a Latino citizen voting age population greater than 50%, as do 11 of the 40 Senate districts and 16 of the 52 congressional districts.

That’s an increase of six Assembly districts, four Senate districts and six congressional districts.

Yet the commission’s first randomly selected members drew criticism for lacking sufficient Latino representation, recalled commission spokesman Fredy Ceja. Its work was further complicated by the coronavirus pandemic, which among other things delayed census data intrinsic to drawing the maps.

The redrawn district lines already have prompted a flurry of lawmakers’ retirement announcements, will force others to move into new districts and court new voters, and in some cases will pit incumbents of the same or opposing parties in struggles for their political lives.

“In order to please and honor the desires of some, we knew that we would disappoint others, and for me that was a heartbreaking process,” said the Rev. Trena Turner, a Democratic commissioner.

“And it seemed to me that it would be so easy if we had a square state, if we didn’t lose a congressional seat,” she added.

Though much of its work was streamed live and it took hours of public comments, some criticized the commission for lacking transparency. A prominent Republican attorney’s lawsuit alleging conflicts and closed-door meetings was recently denied by the California Supreme Court.

Commissioners scrambled to tweak draft maps during about 150 live public meetings, backtracked in some cases from complaints that draft maps would split cities or communities of interest, or jousted over one later withdrawn congressional district that one expert dubbed the “ribbon of shame.”

“Just because a district looks kind of complicated does not mean it’s gerrymandered,” said Russell Yee, a Republican and the commission’s vice-chairman. “Often it’s the most fair, especially given California’s complicated geography, demography.”

Sometimes new draft maps weren’t posted online for days, complicating efforts to parse the changes.

“While the process was at times messy, it was an exercise in democracy done in public,” California Common Cause executive director Jonathan Mehta Stein said in a statement.

That met the goal that his organization and others had in 2008 when they persuaded voters to take the redistricting out of the hands of public officials who had a vested interest in the outcome.

This year’s effort, despite criticism, “put the California public in the driver’s seat,” he said, though the groups promised to seek improvements for the 2031 commission.

California is one of 10 states that empowers an independent commission to draw lines, rather than judges or partisan lawmakers, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

“The maps we created and approved are far from perfect, but they represent the wishes of the people of California who transformed the redistricting process from one that used to take place behind closed doors to one that is public and fully transparent,” said Ahmad, who has no party preference.

The 14-member commission was picked during a lengthy process run by the state auditors office. By law it included five registered Republicans, five registered Democrats and four people registered without a political party.

“I would say this was the most open, most participatory redistricting process in all history,” said Yee, the Republican vice chairman. “In our nation right now where others, unfortunately, in some places have been working to further restrict voting rights and to make redistricting less accessible, we in California here are doing just the opposite.”