NEW YORK (AP) — It was 30 years ago when he last filmed a concert special.

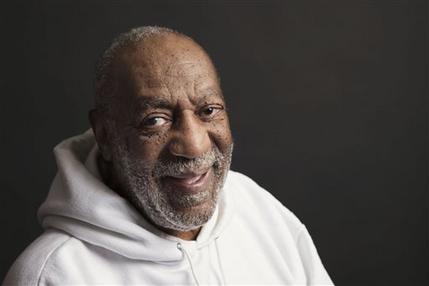

Now he’s gone and done it again. “Bill Cosby: Far From Finished” finds this king of comedy onstage in Cerritos, Calif., where he rules for the 90-minute special airing Saturday on Comedy Central (8 p.m. EST).

Still, it’s fair to ask: Why so long a break, and why now for his return?

“There’s a gap,” says Cosby during an interview this week, “between people knowing what I do and really believing that I still do that – and wondering what it is I really do.”

This audience-awareness gap, he believes, is among the younger demo drawn to Comedy Central. He aims to school those viewers in the principle established by his 1963 debut album: “Bill Cosby Is a Very Funny Fellow … Right!”

Since the early 1960s, Cosby has had a stellar career, including records, books, films and social advocacy. And, of course, television, where he broke the color barrier in the first of his many series, “I Spy,” in the `60s, and scored stratospheric success with “The Cosby Show” (1984-92).

Now, at age 76, he keeps up a busy itinerary doing the thing that got him started: being onstage saying things all sorts of people find funny and true.

So, another question: Why keep up this grueling pace?

“I don’t do anything,” he contends in his meandering style. “I go to the airport and people come up to me while we’re waiting for the flight: `May I take a picture?’ Click, click.”

And then, just like that (or he would have you believe), he takes the stage somewhere and it’s showtime.

“I take a bow. I grab the mic and I begin to put it on. And we’re in show business! It is wonderful and I just enjoy it!”

On his new special, as always, Cosby frames life in universal terms, albeit now from the perspective of a septuagenarian with a solid if sometimes trying marriage, plus kids and grandkids, a sweet tooth he shouldn’t indulge, and a habit of losing things.

“I’m telling you now, I’m not afraid to say it, I lost my key,” he tells the audience with leisurely yet manicured pacing: “It was given to me. I lost my key to the house. That was 48 years ago. I don’t have a key.”

The audience eats it up, rewarding Cosby, he says, with “a sense of how much they understand and trust” him.

“With that, it raises the self-esteem,” he goes on, as if at this phase of his storied career self-esteem were ever at issue, “and I am now driving as a coachman would, with some horses that can really moooove out.

“But you don’t want to go TOO fast,” he cautions, “because you have the carriage you’re on, the wheels, the balance.”

Meanwhile, what you don’t have, if you’re Cosby, is jokes.

“NO jokes! I tell stories,” he declares. “Because I believe you can do things that joke tellers can’t do, and that is, bring your audience along.”

That’s what he discovered at Temple University in 1960, when, as a lad from a downtrodden Philly neighborhood, he rose to the challenge of his Remedial English professor. The assignment was to write a theme about the first time he’d ever done something. Cosby wrote an account of having pulled one of his own teeth. The professor gave him his first-ever A.

Not too much later, Cosby had vaulted to New York’s Greenwich Village as a burgeoning stand-up. He speaks of consorting with the likes of Richie Havens, Richard Pryor and Peter, Paul and Mary – “people who were going to be somebody someday.”

He landed a gig at a club on MacDougal Street “where I came on at 8 and left at 4 in the morning, and my job description was to break up the monotony of the folk singers.

“And over the club,” he goes on, savoring the memory, “was a store that sold very cheap beads, things like that, and was run by a retired ventriloquist, an alcoholic. The story on him was, he had become jealous of his dummy and one night, in a drunken rage, he shot the dummy, then retired.” Cosby is wearing a mischievous grin. “I’m serious!”

Soon he was a star, having soared after making a key decision as he surveyed other rising black comedians, who typically tailored their acts to their identity and experiences as black men.

“I figured, if Godfrey Cambridge does this, if Dick Gregory does this, there’s no need for ALL of us to do it,” Cosby says. “So I decided a very simple thing: I’m not going to tell you what color I am. If you’re unsighted, your friends will tell you!”

But whatever your color, “you can identify with what I’m talking about. It goes all the way back to freshman Remedial English: I never said, `And I looked at my black face and my tooth was white.’”

Cosby chuckles again at that messy self-extraction and adds, “There WAS a lot of red.”