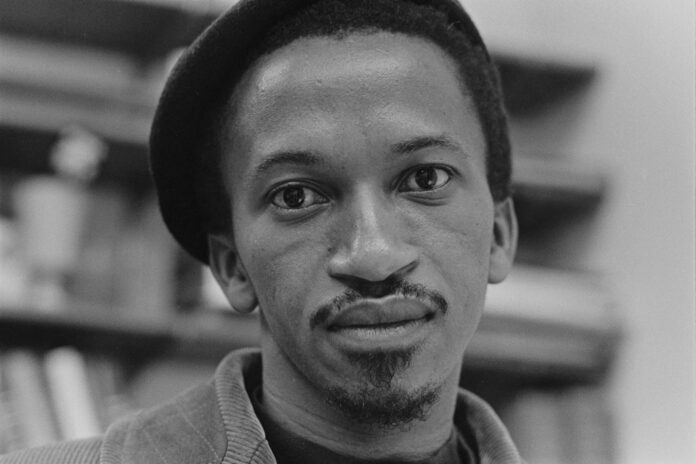

NEW YORK (AP) — When the photographer Ernest Cole died in 1990 at the age of 49 from pancreatic cancer at a Manhattan hospital, his death was little noted.

Cole, one of the most important chroniclers of apartheid-era South Africa, was by then mostly forgotten and penniless. Banned by his native country after the publication of his pioneering photography book “House of Bondage,” Cole had emigrated in 1966 to the United States. But his life in exile gradually disintegrated into intermittent homelessness. A six-paragraph obituary in The New York Times ran alongside a list of death notices.

But Cole receives a vibrant and stirring resurrection in Raoul Peck’s new film “Ernest Cole: Lost and Found,” narrated in Cole’s own words and voiced by LaKeith Stanfield. The film, which opens in theaters Friday, is laced throughout with Cole’s photographs, many of them not before seen publicly.

As he did in his Oscar-nominated James Baldwin documentary “I Am Not Your Negro,” the Haitian-born Peck shares screenwriting credit with his subject. “Ernest Cole: Lost and Found” is drawn from Cole’s own writings. In words and images, Peck brings the tragic story of Cole to vivid life, reopening the lens through which Cole so perceptively saw injustice and humanity.

“Film is a political tool for me,” Peck said in a recent interview over lunch in Manhattan. “My job is to go to the widest audience possible and try to give them something to help them understand where they are, what they are doing, what role they are playing. It’s about my fight today. I don’t care about the past.”

“Ernest Cole: Lost and Found” is a movie layered with meaning that goes beyond Cole’s work. It asks questions not just about the societies Cole documented but of how he was treated as an artist, drawing uncomfortable parallels between apartheid and post-Jim Crow America. In the U.S., Cole was given a Ford Foundation grant to capture Black life in rural and urban areas, but he struggled to find a foothold professionally. Some editors said his images lacked “edge.”

In 2017, more than 60,000 of Cole’s 35mm film negatives were discovered in a bank vault in Stockholm, Sweden. Much of that material, including thousands of photographs Cole took in the U.S., was believed lost. Answers for how they had gotten there, and why they hadn’t been known about earlier were hard to come by. “Lost and Found” portrays the struggle of Cole’s estate to acquire the collection. Only on the eve of the film’s Cannes Film Festival premiere in May did the bank finally announce the handover of most materials to the estate.

What those photographs reveal is an artist who made much more than indelible images of apartheid life. Cole’s early photographs, published in 1967, offered one of the most illustrative and damning portraits of apartheid to Western eyes, including a widely reproduced photograph of a middle-aged woman sitting on a park bench that read “European’s only.” But he was an equally astute and sensitive observer of the segregations, and multicultural joys, of American life.

“It’s a matter of survival,” Stanfield narrates as Cole. “Steal every moment.”

For Peck, the themes of “Ernest Cole: Lost and Found” are deeply personal. The 71-year-old filmmaker, a former minister of culture in Haiti, has spent much of his artistic life also away from his native country, in Berlin, Paris and New York. He dedicates the movie “to those who died in exile.”

“When I say that, that’s most of my friends,” he says. “I recognize all the steps. When you take a contact sheet, I see myself.”

For some four decades, Peck has made some of the most urgent films, in both fiction (including 2000’s “Lumumba,” about the exiled Congo leader) and non-fiction (including last year’s “Silver Dollar Road” ). But he has rarely not employed both narrative and documentary elements in films that take their own shape — movies less interested in genre distinctions than they are pursuing unexamined truths.

That’s made Peck an increasingly exceptional figure in a documentary world that’s become more and more dominated by glossier, less probing films for streaming platforms.

“It’s gotten worse. There’s less money so young people are desperate and accept stuff that my generation would never accept,” Peck says. “The whole industry has changed. I knew another world, and I recognize it’s not that anymore.”

Peck is currently editing a documentary on George Orwell. Like “Ernest Cole: Lost and Found,” it will be told totally in Orwell’s words. A few days after the U.S. election, Peck was working to update a moment in the film that touches on President-elect Donald Trump. Peck has been astonished at how prescient Orwell was on so many current issues — misinformation, AI, social media, the refugee crisis.

“He was a really incredible critic of history and how history is even told,” says Peck. “Before plunging into it, I did not realize how sharp he was about what’s going on today.”

“To me,” he adds, “a film has value if it’s talking to us today.”