By Emily Kim Jenkins, Contributing Writer

Gus Thompson was born into slavery sometime in the early 1860s. The city of Coronado was founded shortly after, in 1880. Two years after that, in 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act was ratified, the only immigration law ever enacted to explicitly exclude a certain nationality. In 2024, San Diego State University’s Black Resource Center received the largest donation in the center’s history in the names of Gus and Emma Thompson.

These seemingly disconnected events are each deeply tied to the heartwarming story that led brothers Ron and Lloyd Dong Jr. to make a $5 million donation to the center.

After slavery was abolished, Thompson moved to Coronado, where he began to work for Elisha S. Babcock, a founder of the Hotel del Coronado and prominent businessman of the area. He and his wife, Emma, were two of the first permanent residents of Coronado in the early 1880s, right around the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act.

The act, signed by former President (and outspoken abolitionist) Chester Arthur, prohibited any Chinese immigrant laborers from entering the country. Through a treaty with China, the United States had previously allowed Chinese immigrants to enter the country but not become citizens, according to Elizabeth McPhail for the San Diego History Journal. As anti-Chinese and anti-immigrant rhetoric was increasing nationwide, it also increased in San Diego. Access to the bay meant a rise in Chinese presence in the fishing industry and direct access to the border meant a higher law enforcement presence (and subsequently more arrests) after the enactment of the Chinese Exclusion Act. The act was

For Chinese immigrants still in the country at the time, like the Dong brothers’ parents, this heightened tension created strife in their personal lives. Few people in the country were likely to sell or rent their homes to anyone of Chinese descent. The Thompsons had moved to San Diego and, upon learning of the young family in need of a place to live, rented their Coronado home to Lloyd Sr. and Margaret Dong.

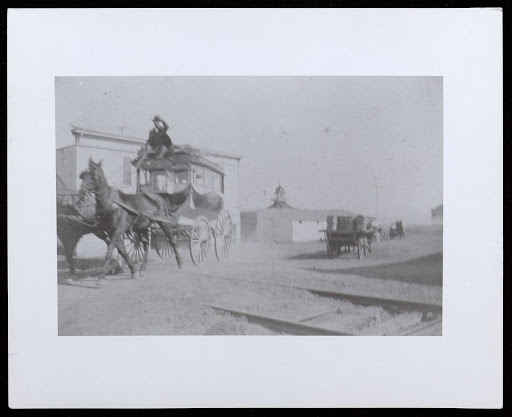

Thompson had created a name for himself and used his resources to help others regularly. He built a livery stable with a boardinghouse for Black people in need of a place to sleep. When he died, Emma sold the house to the Dong family, giving them a rare and significant gift.

“Given what I know of my great-grandparents through my grandmother, I don’t think that it was something that they thought a whole lot about,” Bollinger Kemp III, the Thompsons’ great-grandson told the New York Times. “It was just the right thing to do.”

Earlier this year, the brothers Ron and Lloyd Dong Jr. visited their childhood home with their spouses, Janice and Girina, in Coronado for a final time. After moving to other cities and the passing of their other two siblings, it was time to sell the house on C Street.

“When you look at all the things that Gus Thompson did, he did a lot of things for a lot of other people, things that they might otherwise could never have done themselves,” Ron Dong said. “We wanted to do something to repay him, to give back.”

So, upon the sale of the house and the apartment next to it (formerly Thompson’s livery stable, which the Dongs later converted), the Dongs decided to donate $5 million from the home’s sale to SDSU’s Black Resource Center. Originally, the family considered donating it in the form of scholarships, but in her research, she found that underrepresented student communities often need support outside of just financial aid, so she decided to give it to the Black Resource Center instead.

Dr. Tonika Green, a professor at SDSU and associate vice president of Campus Community Affairs, works with the Black Resource Center frequently.

“This is bigger than what we imagined, this helps us think bigger, impact more lives, and witness dreams come true right before our eyes. The Dong Family will change lives with this gift,” Green said in a statement. ”It’s the gift that never stops giving.”

Both tragic and triumphant, Asian American immigration in the United States is a struggle not often taught in school curriculums. May is Asian American & Pacific Islander Heritage Month. To learn more about the Asian American struggle in San Diego, you can attend one of the San Diego City Library’s events, visit the San Diego Chinese Historical Museum, or explore the San Diego History Journal online.

This resource is supported in whole or in part by funding provided by the State of California, administered by the California State Library in partnership with the California Department of Social Services and the California Commission on Asian and Pacific Islander American Affairs as part of the Stop the Hate program. To report a hate incident or hate crime and get support, go to https://www.cavshate.org/.