By Latanya West, Voice & Viewpoint Managing Editor

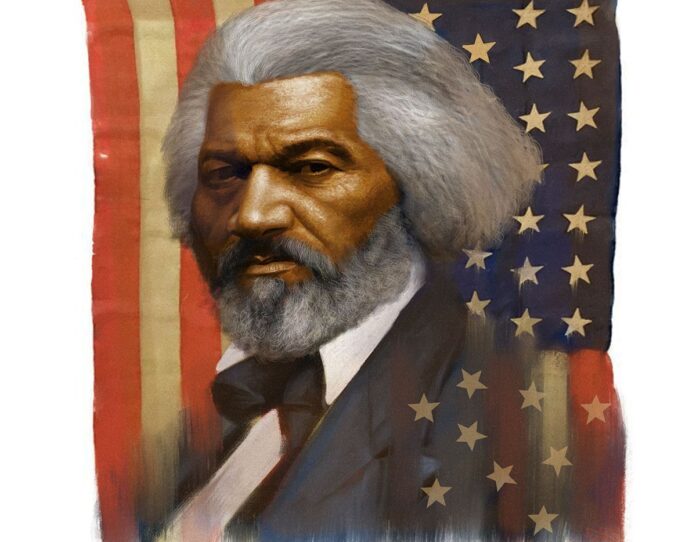

Frederick Douglass is arguably one of the most influential figures in American history. An internationally renowned orator, statesman, anti-slavery crusader, and author, the child born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, came to exemplify what is best and most enduring about American ideals and the promise of our country’s constitution.

Douglass used words to eloquently and unapologetically speak, write, and educate northern whites about American slavery. He unapologetically named in detail after detail slavery’s horrific injustices, white slavemasters’ and even religious abolitionists’ moral ineptitude, and called to task northern whites who turned a blind eye to slavery’s insidiousness. He called on all Americans to look directly and unflinchingly at slavery’s cost, not only for America’s slaves, but also for the entire nation.

At a time when freedom was only a vague promise on the horizon for most black Americans, Douglass was a resounding voice of hope, justice, and dignity for African Americans. He elevated the national discussion on slavery, helping to hasten its demise.

Here is a brief biography of the man known as the “Prophet of Freedom”:

EARLY LIFE

Douglass’ early life was lonely and tragic. Born a slave sometime in 1818 in Talbot County,

Maryland, Frederick Douglass’ father was rumored to be his mother’s white slave owner. His mother, who was enslaved on a nearby plantation, would walk twelve miles to visit her son until her untimely death when Frederick was a young boy. Viewed as property to be bought, sold, or transferred in ownership, Douglass was hired out as cheap labor to a number of slave masters.

Long before his physical freedom, Frederick was liberated by the power of words. Ignoring the laws of the times, one of Frederick’s slave mistresses taught him the alphabet. It proved to be a transformative event in Douglass’ life. He recounts in his 1845 bestselling autobiography that “Learning the alphabet gave me the key to reading; I took that key and, with a little help from my friends, learned how to read, thus becoming a free man in my mind.” With an audacious sense of purpose that flowered as he matured into adulthood, the young Frederick convinced his white childhood friends to teach him to read and write in exchange for food. He read at every opportunity, even after being sold into hard slave labor in rural Maryland. His steely desire for knowledge never faltered. He soon organized a Sunday school for fellow slaves and quickly earned a reputation for being a headstrong troublemaker.

In 1836, Douglass impersonated a sailor and escaped to freedom during a time when abolitionist fervor was growing across the U.S. He married Anna Murray, a free black woman instrumental in his escape, and settled in New Bedford, Massachusetts. While working as a laborer to support his young family Douglass began to frequent anti-slavery rallies. He was soon up on stage, reluctantly but powerfully sharing his story.

VANGUARD OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT

1841 proved to be a fateful year for Douglass. He gave his first major speech at the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society’s annual convention and launched his influential career as an antislavery crusader. The famed abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison was so moved by Frederick’s magnetic stage presence and powerful personal story that he enlisted him to lecture with the American Anti-Slavery Society at meeting halls across the Eastern and Midwestern United States. It was often dangerous work. Douglas became known for his clear, direct, and articulate oratory style. He spoke truthfully and eloquently about his life as a slave, sometimes inciting riotous mobs that weren’t ready to face the American south’s horrifying and morally inept “peculiar institution.”

Douglass’ first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, mentioned details about his life as a slave, including the name and residence of his former master. To avoid recapture, Frederick spent two years touring and lecturing to abolitionists in Great Britain. The tour earned him international fame and he returned to the States intent on helping African Americans gain the freedoms he enjoyed while abroad.

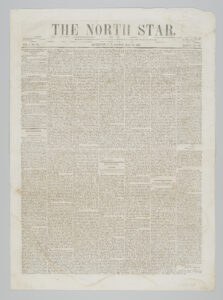

In 1847 he began publication on The North Star, his uniquely successful and influential anti-slavery newspaper, so named for the bright star said to guide fugitive slaves to freedom along the Underground Railroad. In numerous speeches, writings, and publications, Douglass doggedly promoted the end of slavery. During this time, Douglass was also a conductor on the Rochester, New York arm of the Underground Railroad. He recounts in his 1882 autobiography, The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, that his home served as one of the Underground Railroad’s main stations and helped spirit runaway slaves to Canada and freedom.

Douglass’ fame and influence grew as the abolitionist movement and the political winds of change brought the issue of slavery to the forefront of American politics. His second autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom, is a more detailed account of his life as a slave and his evolution as a thinking, self-made man who valued faith and literacy. When the Civil War broke out, Douglass’ morally persuasive arguments against slavery were at the vanguard of slavery’s demise.

When Douglass spoke, national leaders paid attention. Douglass outspokenly called for the right of black men to fight for their freedom and boldly petitioned President Lincoln for the fair and equal treatment of African American men in uniform. He helped recruit troops for the first official Civil War infantry of free northern black men. Immortalized in the 1989 movie Glory, the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment significantly contributed to the war’s effort in the famed fight for Fort Wagner and helped legitimize black troops.

Never one to shy away from controversy, Douglass was also an early supporter of the women’s suffrage movement.

LATER YEARS

After the Civil War, the former slave continued his appointment with destiny. In the mid-1870’s, Douglass moved to Washington, DC and served in a number of prominent presidential appointments: U.S. Marshall (1877 – 1881) and Recorder of Deeds for the District of Columbia (1881 – 1886). He was chargé d’affaires for Santo Domingo and minister to Haiti (1889-1891). In 1874 he was appointed President of the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company, popularly known as the Freedman’s Savings Bank, the first savings institution established by the U.S. government to assist former slaves and African-American Civil War veterans during the Reconstruction era.

Buoyed by the Civil War victory but bitterly disturbed by the failures of Reconstruction, Douglass was a vigorous opponent of Jim Crow segregation until his death from a heart attack in 1895.

ENDURING LEGACY

Cedar Hill, Douglass’ family home, is maintained as a part of the National Park Service and was designated a National Historic Site in 1988. His great great granddaughter Nettie Washington Douglass established the Frederick Douglass Family Initiatives to preserve his legacy and create awareness about modern day slavery, which today affects an estimated 27 million people worldwide. Visit www.fdfi.org to learn more.

The Meaning of July Fourth for the Negro

Well before President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, and well before June 19, 1865, when news of freedom finally reached over 250, 000 Galveston, Texas slaves, Frederick Douglass reflected on the paradoxical nature of the nation’s Fourth of July Independence Day celebrations in his July 5, 1852 speech “What, to the Slave, is the Fourth of July?” While change has come, there are still battles to be won for equal rights, equal access, and equal protections under the law. For Black people, the words of Frederick Douglass still resonate today. For some, the July Fourth holiday is cause for anticipatory celebration, others choose not to celebrate it all, while others celebrate the day with some reticence.

– Dr. John E. Warren, Publisher

The Words of Frederick Douglass, July 5, 1852

Excerpt from “What, to the Slave, is the Fourth of July”

Fellow Citizens, I am not wanting in respect for the fathers of this republic. The signers of the Declaration of Independence were brave men. They were great men, too. Great enough to give frame to a great age. It does not often happen to a nation to raise, at one time, such a number of truly great men. The point from which I am compelled to view them is not, certainly, the most favorable; and yet I cannot contemplate their great deeds with less than admiration. They were statesmen, patriots and heroes, and for the good they did, and the principles they contended for, I will unite with you to honor their memory….

…Fellow-citizens, pardon me, allow me to ask, why am I called upon to speak here to-day? What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence? Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us?

And am I, therefore, called upon to bring our humble offering to the national altar, and to confess the benefits and express devout gratitude for the blessings resulting from your independence to us?

Would to God, both for your sakes and ours, that an affirmative answer could be truthfully returned to these questions! Then would my task be light, and my burden easy and delightful. For who is there so cold, that a nation’s sympathy could not warm him? Who so obdurate and dead to the claims of gratitude, that would not thankfully acknowledge such priceless benefits? Who so stolid and selfish, that would not give his voice to swell the hallelujahs of a nation’s jubilee, when the chains of servitude had been torn from his limbs? I am not that man. In a case like that, the dumb might eloquently speak, and the “lame man leap as an hart.”

But such is not the state of the case. I say it with a sad sense of the disparity between us. I am not included within the pale of glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought light and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn.

To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty, and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony. Do you mean, citizens, to mock me, by asking me to speak to-day? If so, there is a parallel to your conduct. And let me warn you that it is dangerous to copy the example of a nation whose crimes, towering up to heaven, were thrown down by the breath of the Almighty, burying that nation in irrevocable ruin! I can to-day take up the plaintive lament of a peeled and woe-smitten people!

“By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down. Yea! We wept when we remembered Zion. We hanged our harps upon the willows in the midst thereof. For there, they that carried us away captive, required of us a song; and they who wasted us required of us mirth, saying, Sing us one of the songs of Zion. How can we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land? If I forget thee, 0 Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning. If I do not remember thee, let my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth.”

Fellow-citizens, above your national, tumultuous joy, I hear the mournful wail of millions! whose chains, heavy and grievous yesterday, are, to-day, rendered more intolerable by the jubilee shouts that reach them. If I do forget, if I do not faithfully remember those bleeding children of sorrow this day, “may my right hand forget her cunning, and may my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth!” To forget them, to pass lightly over their wrongs, and to chime in with the popular theme, would be treason most scandalous and shocking, and would make me a reproach before God and the world. My subject, then, fellow-citizens, is American slavery. I shall see this day and its popular characteristics from the slave’s point of view. Standing there identified with the American bondman, making his wrongs mine, I do not hesitate to declare, with all my soul, that the character and conduct of this nation never looked blacker to me than on this 4th of July! Whether we turn to the declarations of the past, or to the professions of the present, the conduct of the nation seems equally hideous and revolting. America.is false to the past, false to the present, and solemnly binds herself to be false to the future.

Standing with God and the crushed and bleeding slave on this occasion, I will, in the name of humanity which is outraged, in the name of liberty which is fettered, in the name of the constitution and the Bible which are disregarded and trampled upon, dare to call in question and to denounce, with all the emphasis I can command, everything that serves to perpetuate slavery Ñ the great sin and shame of America! “I will not equivocate; I will not excuse”; I will use the severest language I can command; and yet not one word shall escape me that any man, whose judgment is not blinded by prejudice, or who is not at heart a slaveholder, shall not confess to be right and just.

But I fancy I hear some one of my audience say, “It is just in this circumstance that you and your brother abolitionists fail to make a favorable impression on the public mind. Would you argue more, and denounce less; would you persuade more, and rebuke less; your cause would be much more likely to succeed.” But, I submit, where all is plain there is nothing to be argued. What point in the anti-slavery creed would you have me argue? On what branch of the subject do the people of this country need light? Must I undertake to prove that the slave is a man? That point is conceded already. Nobody doubts it. The slaveholders themselves acknowledge it in the enactment of laws for their government. They acknowledge it when they punish disobedience on the part of the slave. There are seventy-two crimes in the State of Virginia which, if committed by a black man (no matter how ignorant he be), subject him to the punishment of death; while only two of the same crimes will subject a white man to the like punishment.

What is this but the acknowledgment that the slave is a moral, intellectual, and responsible being? The manhood of the slave is conceded. It is admitted in the fact that Southern statute books are covered with enactments forbidding, under severe fines and penalties, the teaching of the slave to read or to write. When you can point to any such laws in reference to the beasts of the field, then I may consent to argue the manhood of the slave. When the dogs in your streets, when the fowls of the air, when the cattle on your hills, when the fish of the sea, and the reptiles that crawl, shall be unable to distinguish the slave from a brute, then will I argue with you that the slave is a man!

For the present, it is enough to affirm the equal manhood of the Negro race. Is it not astonishing that, while we are ploughing, planting, and reaping, using all kinds of mechanical tools, erecting houses, constructing bridges, building ships, working in metals of brass, iron, copper, silver and gold; that, while we are reading, writing and ciphering, acting as clerks, merchants and secretaries, having among us lawyers, doctors, ministers, poets, authors, editors, orators and teachers; that, while we are engaged in all manner of enterprises common to other men, digging gold in California, capturing the whale in the Pacific, feeding sheep and cattle on the hill-side, living, moving, acting, thinking, planning, living in families as husbands, wives and children, and, above all, confessing and worshiping the Christian’s God, and looking hopefully for life and immortality beyond the grave, we are called upon to prove that we are men!

Would you have me argue that man is entitled to liberty? that he is the rightful owner of his own body? You have already declared it. Must I argue the wrongfulness of slavery? Is that a question for Republicans? Is it to be settled by the rules of logic and argumentation, as a matter beset with great difficulty, involving a doubtful application of the principle of justice, hard to be understood? How should I look to-day, in the presence of Amercans, dividing, and subdividing a discourse, to show that men have a natural right to freedom? speaking of it relatively and positively, negatively and affirmatively. To do so, would be to make myself ridiculous, and to offer an insult to your understanding. There is not a man beneath the canopy of heaven that does not know that slavery is wrong for him.

What, am I to argue that it is wrong to make men brutes, to rob them of their liberty, to work them without wages, to keep them ignorant of their relations to their fellow men, to beat them with sticks, to flay their flesh with the lash, to load their limbs with irons, to hunt them with dogs, to sell them at auction, to sunder their families, to knock out their teeth, to burn their flesh, to starve them into obedience and submission to their masters? Must I argue that a system thus marked with blood, and stained with pollution, is wrong? No! I will not. I have better employment for my time and strength than such arguments would imply.

What, then, remains to be argued? Is it that slavery is not divine; that God did not establish it; that our doctors of divinity are mistaken? There is blasphemy in the thought. That which is inhuman, cannot be divine! Who can reason on such a proposition? They that can, may; I cannot. The time for such argument is passed.

At a time like this, scorching irony, not convincing argument, is needed. O! had I the ability, and could reach the nation’s ear, I would, to-day, pour out a fiery stream of biting ridicule, blasting reproach, withering sarcasm, and stern rebuke. For it is not light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder. We need the storm, the whirlwind, and the earthquake. The feeling of the nation must be quickened; the conscience of the nation must be roused; the propriety of the nation must be startled; the hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed; and its crimes against God and man must be proclaimed and denounced.

What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer; a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciation of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade and solemnity, are, to Him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy — a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages.There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices more shocking and bloody than are the people of the United States, at this very hour.

Go where you may, search where you will, roam through all the monarchies and despotisms of the Old World, travel through South America, search out every abuse, and when you have found the last, lay your facts by the side of the everyday practices of this nation, and you will say with me, that, for revolting barbarity and shameless hypocrisy, America reigns without a rival….

…Allow me to say, in conclusion, notwithstanding the dark picture I have this day presented, of the state of the nation, I do not despair of this country. There are forces in operation which must inevitably work the downfall of slavery. “The arm of the Lord is not shortened,” and the doom of slavery is certain. I, therefore, leave off where I began, with hope. While drawing encouragement from “the Declaration of Independence,” the great principles it contains, and the genius of American Institutions, my spirit is also cheered by the obvious tendencies of the age. Nations do not now stand in the same relation to each other that they did ages ago. No nation can now shut itself up from the surrounding world and trot round in the same old path of its fathers without interference. The time was when such could be done. Long established customs of hurtful character could formerly fence themselves in, and do their evil work with social impunity. Knowledge was then confined and enjoyed by the privileged few, and the multitude walked on in mental darkness. But a change has now come over the affairs of mankind. Walled cities and empires have become unfashionable. The arm of commerce has borne away the gates of the strong city.

Intelligence is penetrating the darkest corners of the globe. It makes its pathway over and under the sea, as well as on the earth. Wind, steam, and lightning are its chartered agents. Oceans no longer divide, but link nations together. From Boston to London is now a holiday excursion. Space is comparatively annihilated. — Thoughts expressed on one side of the Atlantic are distinctly heard on the other.

The far off and almost fabulous Pacific rolls in grandeur at our feet. The Celestial Empire, the mystery of ages, is being solved. The fiat of the Almighty, “Let there be Light,” has not yet spent its force. No abuse, no outrage whether in taste, sport or avarice, can now hide itself from the all-pervading light. The iron shoe, and crippled foot of China must be seen in contrast with nature. Africa must rise and put on her yet unwoven garment. ‘Ethiopia, shall, stretch. out her hand unto Ood.” In the fervent aspirations of William Lloyd Garrison, I say, and let every heart join in saying it:

God speed the year of jubilee

The wide world o’er!

When from their galling chains set free,

Th’ oppress’d shall vilely bend the knee,

And wear the yoke of tyranny

Like brutes no more.

That year will come, and freedom’s reign,

To man his plundered rights again

Restore.

God speed the day when human blood

Shall cease to flow!

In every clime be understood,

The claims of human brotherhood,

And each return for evil, good,

Not blow for blow;

That day will come all feuds to end,

And change into a faithful friend

Each foe.

God speed the hour, the glorious hour,

When none on earth

Shall exercise a lordly power,

Nor in a tyrant’s presence cower;

But to all manhood’s stature tower,

By equal birth!

That hour will come, to each, to all,

And from his Prison-house, to thrall

Go forth.

Until that year, day, hour, arrive,

With head, and heart, and hand I’ll strive,

To break the rod, and rend the gyve,

The spoiler of his prey deprive —

So witness Heaven!

And never from my chosen post,

Whate’er the peril or the cost,

Be driven.

The Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass, Volume II

Pre-Civil War Decade 1850-1860

Philip S. Foner

International Publishers Co., Inc., New York, 1950