By Brian Mahoney, AP Basketball Writer

A career in the NBA seemed such an uncertainty as the 1950s arrived that Bob Cousy considered driving school a better option than playing for a team he didn’t even know how to find on a map.

“Basketball was at the bottom of the totem pole,” said Cousy, one of the sport’s few bankable stars at the time.

The NBA, known today as a leader when it comes to culture and racial issues, was anything but at a time when segregation divided the country. It was a powerless, fledgling league trying to find its footing. Franchises were folding and few paid much attention to the NBA.

When Jackie Robinson became Major League Baseball’s first Black player in 1947, Cousy remembered it being major national news.

Three years later, Cousy’s Boston Celtics made Chuck Cooper the NBA’s first Black player to be drafted.

“And to this day I have yet to read a story about Chuck Cooper breaking the color line in the NBA, because as I say nobody gave a damn what color we were or what we were doing,” said Cousy, now 93.

The powerless NBA largely sat idly by, watching events like the Supreme Court ruled on Brown v. Board of Education challenging racial segregation in public schools, Rosa Parks refusing to give up her seat on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama, and national guard troops being sent to Little Rock, Arkansas, to enforce desegregation and protect the Little Rock Nine at Central High School.

However, a foundation was being built for what, as the NBA begins its 75th season, is one of the most influential sports leagues in the world — on and off the court. The 1950s would bring in the league’s first Black stars. The decade also saw the advent of the 24-second shot clock, which sped up the game and made it a more attractive product.

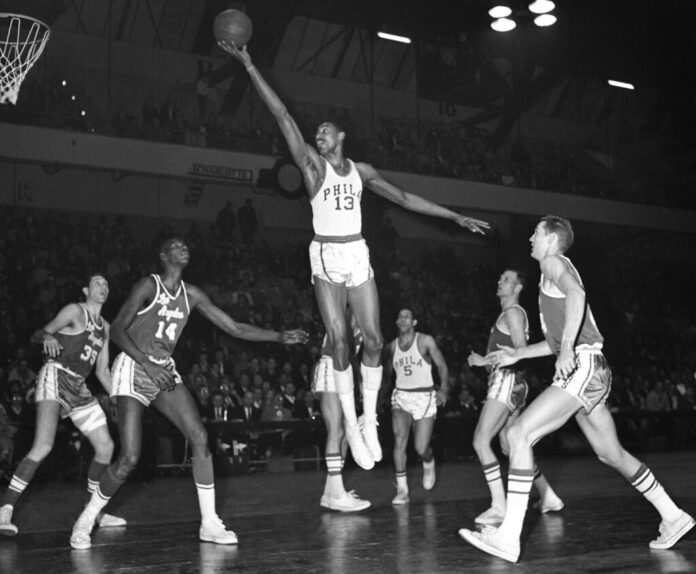

Outspoken and fiercely independent Black stars like Bill Russell, Wilt Chamberlain and Elgin Baylor became part of the NBA fabric in the 1950s. They brought a higher level of all-around skill and athleticism — along with attributes that would later make the Hall of Famers social and cultural icons off the court — and predecessors for today’s All-Stars.

“I think one thing that’s true in sports throughout time is that our heroes are people that, on some level we identify with them,” said Johnny Smith, a professor of sports history at Georgia Tech whose research focuses on the history of sports and American culture.

“But if you go back to the ’50s and the ’60s, this was a moment of the civil rights movement, when Black athletes were breaking through, integrating professional sports leagues — the NBA, the NFL, you go back to Jackie Robinson and Major League Baseball — and they became symbols of racial pride, symbols of Black achievement and that mattered to folks in the Black community. They could look at someone who had broken a barrier, who had disproven the mythologies around white supremacy.”

But it was a gradual climb to the Celtics dynasty that began just before the decade ended. Cousy was the floor leader of those squads, though when he finished college in 1950, he believed he could make more money by touring New England for exhibition games with his Holy Cross teammates than playing real ones in the NBA.

“There was no interest whatsoever. We were behind baseball, football, hockey and then came basketball in the ’50s,” Cousy said. “Unless you had the Globetrotters as a doubleheader-type thing. Then you’d sell out.”

Or maybe if George Mikan was in town.

The NBA’s first superstar centered its first dynasty, the Minneapolis Lakers. His teams won five titles in six years from 1949-54, but almost all the attention went to the 6-foot-10 Mikan, who wearing his glasses looked more professor than post player.

He would sometimes travel to games ahead of his team to do interviews in hopes of drumming up interest. Once, he arrived for a game at Madison Square Garden to find there was indeed plenty of interest — but mostly in him. The marquee read: Geo Mikan vs. New York Knicks.

Mikan ended up in Minneapolis after his previous team folded and he went to the Lakers in a lottery. That’s the same way Cousy became a Celtic.

An 11-team league when the 1950-51 season began was reduced to 10 by the time it ended, after the Washington Capitols — coached in the late 1940s by future Celtics leader Red Auerbach — disbanded during it.

It was down to nine in time for 1953-54, when the West Division consisted of just four teams and none was anywhere near the West. It was Milwaukee, Minneapolis, Fort Wayne, Indiana, and Rochester — which is only West in New York State.

Cousy wasn’t convinced of the league’s future in 1950. He and a teammate had started a business of driving lessons for women and were planning to open a string of gas stations when he was drafted in the first round by the Tri-Cities Blackhawks.

“I said, ‘Well, I was a pretty good student in school. I must have been asleep in geography class. What the hell is a Tri-City?'” Cousy remembered thinking.

It was the team representing Moline, Illinois, Rock Island, Illinois, and Davenport, Iowa, but no matter. The franchise traded Cousy to the Chicago Stags rather than pay him the $10,000 a year he sought. He never played there either, after they folded.

Cousy became a Celtic in time for the 1950-51 season, also Cooper’s first season. Though Cooper was the first Black drafted in the NBA, Earl Lloyd was the first to play in a game that season. And Nat “Sweetwater” Clifton of the Knicks was the first Black player to sign a contract.

The fragile state of the league left in many ways left it standing on the sidelines when it came to social issues.

Though Cousy praises the way Boston owner Walter Brown, Auerbach and the Celtics organization handled integration, though they couldn’t escape the indignities.

The team was playing an exhibition game in Raleigh, North Carolina a few years after Cooper was drafted. He wasn’t allowed to stay in the team hotel. Cousy volunteered to ride the train back to Boston with him and was disheartened to find separate restrooms in the train station.

“Neither one of us had ever seen those dreaded big white signs with the arrow,” Cousy said. “Colored pointing one way, white pointing the other.”

They decided to urinate together off the platform rather than use them.

The NBA would stabilize and strengthen as an eight-team league in the late 1950s. The Celtics would win their first title in 1957 in Russell’s rookie season, then take eight in a row from 1959-66.

Baylor was Rookie of the Year in 1958-59. Chamberlain would enter the league the next season. The NBA looked a whole lot better than a decade earlier.

“I’m very proud to have at least helped light the flame,” Cousy said, “helped set the table for what I have seen happening to the sport in my lifetime.”