By Stacy M. Brown, NNPA Newswire Senior National Correspondent

In Pittsburgh’s Hill District, the historic Black Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church will return to its former location.

More than 60 years ago, the church was forced to relinquish its sanctuary to an urban renewal project that destroyed the core of an African American neighborhood.

The church was compensated for a fraction of its value, according to the church.

Now, the church has reached an agreement with the Pittsburgh Penguins, the NHL team that owns the development rights to the site adjacent to its current facility.

According to a report by The Grio, the Penguins have consented to allowing the church to use a 1.5-acre plot of land that the church plans to use for housing and other revenue-generating development.

Kevin Acklin, president of business operations for the Penguins, stated that the organization is “recognizing our role here as a steward” of the property and its history.

Prior to 1967, the Penguins played in a former community arena, and now they play in a newer arena nearby.

According to historians, the Hill District was a center of Black culture in the 20th century, renowned for its jazz clubs and other cultural landmarks depicted in many of acclaimed playwright August Wilson’s works.

In addition, Bethel AME played an important role in that community.

It was founded in 1808 and is regarded as Pittsburgh’s oldest Black church. From its inception, it was involved in infant education and civil rights.

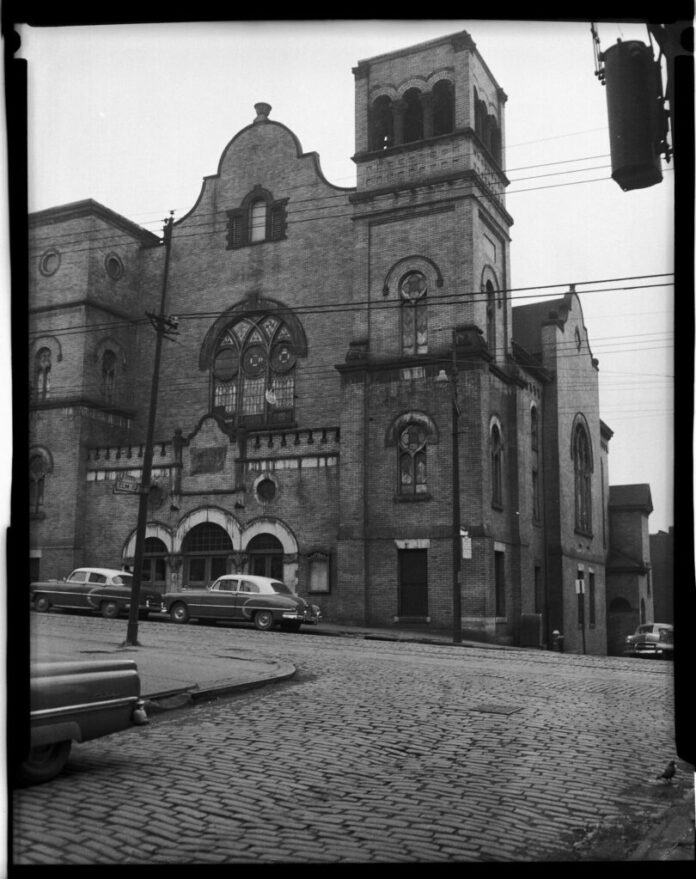

It opened a large brick church with rounded arches and a prominent tower in 1906 in the Lower Hill District, which was home to 3,000 members at its zenith.

In the 1950s, the Pittsburgh Urban Redevelopment Authority declared a large portion of Lower Hill to be derelict.

It oversaw the demolition of approximately 1,300 structures on 95 acres, displacing more than 8,000 individuals, more than 400 businesses, and numerous places of worship.

Bethel congregants stated that the predominantly white Catholic church was not, however, demolished.

Bethel’s leaders battled the church’s demolition unsuccessfully, ultimately receiving $240,000 for a $745,000 property.

The pastor of Bethel, Rev. Dale Snyder, told The Grio, “This is a model for how we can heal the broken realities of America.”

The church intends to construct housing, a daycare center, and other potential commercial developments on the property.

The Rev. Prudence Harris, associate pastor and lifelong Bethel member, stated that she was five years old when she and her parents witnessed the deconstruction of the previous sanctuary.

The agreement was reached after years of public requests and protests by the church.

It is a microcosm of a larger conflict over the legacy of the 1950s project, in which Black community leaders have long sought redress from Pittsburgh’s political, business, and athletic elites.

The Penguins hope that the agreement and the extensive efforts to redevelop the site can serve as a model for other U.S. cities with similar urban renewal scars from the mid-20th century.

“I have never been a devotee of hockey…. AME Third District Bishop Errenous McLoud Jr. thanked the Penguins for turning him into a hockey fan during a news conference on the site Bethel is acquiring.

He stated that this agreement “could and should serve as a model for reparations worldwide.”

The accord is a component of broader efforts to collaborate with Hill District residents to restore the neighborhood’s former connections to downtown.

All of the main parties, including the city, county, and two public authorities, agreed to include Hill District stakeholders in a plan in 2014.

Church leaders stated, “While the agreement is a step toward reparations for the historic Black church and the Hill District, there is still a long way to go in addressing the damage caused in the middle of the 20th century