By John M Sloop, Vanderbilt University

North America’s most diverse professional league kicks off on Feb. 21, 2024, as Major League Soccer returns after a winter break.

The league, commonly known as the MLS, has long prided itself as a standard-bearer for racial and national diversity: Last season saw players from 81 countries across six continents compete for teams. Members of racial minorities make up 63% of players and 36% of head coaches, according to the latest diversity scorecard from the University of Central Florida’s Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport.

As a soccer scholar and author of the book “Soccer’s Neoliberal Pitch,” I know that this diversity is in part by design and has deep roots. Indeed, the MLS had, as a model of diversity, an earlier attempt to get Americans to embrace the “beautiful game”: the North American Soccer League, or NASL.

The fall and rise of the NASL

Most often remembered for bringing Pelé to the U.S., the NASL was arguably the first serious attempt to develop a truly professional “major” soccer league in the country. It ran from 1968 to 1984 and peaked in popularity the mid-1970s.

With minimal audiences at the gates and a TV contract that was scrapped early on because of dismal ratings, the league struggled early on. A full dozen of the 17 inaugural teams folded after the first year, leaving just five competing in the second season. Growth was slow – by 1973 there were nine teams, and games had an average attendance of about 6,000 fans.

Most team owners and league commissioner Phil Woosnam believed the NASL needed more sizzle to appeal to an American market. To that end, the league decided to make a number of alterations. Rules were tweaked to increase the number of goals, and more traditional American sports add-ons – tailgating and cheerleaders, for example – were encouraged to help improve the atmosphere.

But the impulse to alter both the substance and meaning of the game had mixed results, at best. Although the NASL was able to enlarge its audience among a subset of fans through these stylistic distractions, others felt alienated by the focus on razzmatazz.

As Newsweek reported at the time, first-generation immigrants – the demographic expected to make up the supporting base – stayed away. Polls revealed that these traditional soccer supporters perceived the quality of play in the league to be so inferior that they weren’t interested in attending games.

Likewise, European players often found the innovations of the NASL off-putting. After playing his first game for the Portland Timbers, Pat Howard – a former player for the English team Everton – found himself thinking, “What kind of football is this? I mean, there were blinking cavalry charges up the wings, ducks behind the goal, firecrackers going on.”

A study commissioned by the NASL convinced the league that it would have to increase the skill level of the game if it hoped to grab the largest possible viewership. And that is when the story of the league’s diversity really takes off.

A league of nations

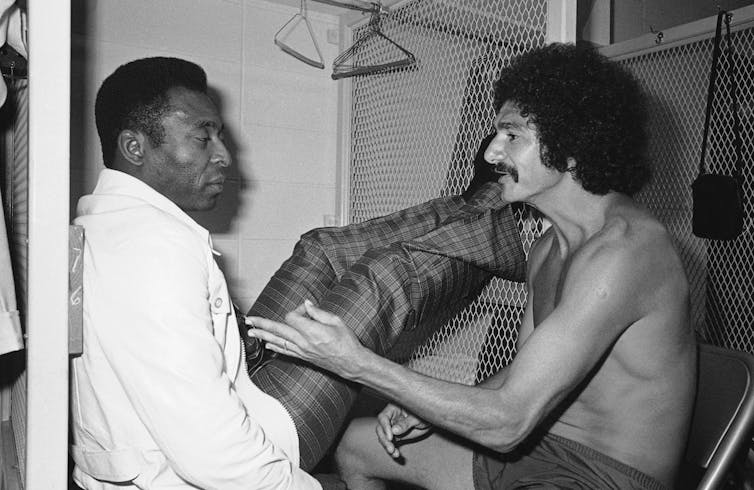

The New York Cosmos, owned by Warner Communications, was one of earliest NASL teams to reach out to international star power, luring Pelé out of retirement to play three seasons for a reported US$4.7 million.

The Cosmos followed the signing by bringing in other global stars, such as Germany’s World Cup winning captain Franz Beckenbauer, Italian Giorgio Chinaglia and Brazilian Carlos Alberto.

Other global stars who signed for different teams included elite global players such as Johan Cruyff, Gerd Müller, Peter Osgood, Bobby Moore, Eusébio and George Best. It represented a who’s who of the soccer world, albeit an aging one.

The impact on the league was immediate. It resulted in increased attendances and a higher media profile in the U.S.

It also set a course for rosters featuring players from around the world – and not only through the import of fading stars.

NASL teams needed to strike a balance – and balance their budgets – by searching for players who were talented but also undervalued. And this often meant bringing in African and African diaspora players. They were aided in their search by overseas racism, both implicit and state-sponsored.

European teams in the 1970s had relatively low numbers of Black players playing in them.

It led players like Trinidad and Tobago’s Leroy DeLeon to choose the NASL rather than sign contracts with European teams. As DeLeon recounted, he decided to join the New York Generals in 1969 after a recruitment trip to England in which he only saw one Black player, West Ham’s Clyde Best. By contrast, the Washington Darts, the team DeLeon later joined, had seven Trinidadians on the roster.

Escaping apartheid

Meanwhile, under the apartheid laws in South Africa, Black and white players were prohibited from playing one another. To Black South Africans, the NASL represented a chance to escape the racism of their homeland.

Patrick “Ace” Ntsoelengoe was one of many Black South Africans who viewed the NASL as being the only route toward international fame. Fellow Black South African Webster Lichaba, who played in Atlanta in the early 1980s, relished his treatment in the U.S.: “You were allowed to eat in any restaurant; you went into any club if you wanted to; you stayed in any area you wanted to. … It was different, a different lifestyle altogether. You were treated as an equal.”

Kaizer Motaung, who played for the Atlanta Chiefs and later returned to South Africa to found the successful Kaizer Chiefs football club, noted: “America was an eye-opener for me. I am in a foreign country, but here are Black people holding high positions being respected worldwide.”

And it wasn’t only Black South Africans who made the move. Apartheid resulted in a sporting boycott of South Africa, preventing the country from playing in international games. As such, the NASL represented an opportunity for white South Africans to play in front of a wider audience.

As soccer scholar Chris Bolsmann has noted, both Black and white players later went back to South Africa, energized to act against apartheid and confident of their ability to succeed in joint struggles again racism.

While some overseas players returned home after their playing careers ended, others stayed to help the grassroots game in the U.S. Trinidad and Tobago goalkeeper Lincoln Phillips, who played for the Baltimore Bays, went on to coach Howard University’s men’s soccer team – the first from a historically Black college or university to win an NCAA soccer championship in 1974 – and later helped found the Black Soccer Coaches Association, an organization designed to help move Black coaches up the administrative ladder in soccer.

A lasting soccer experiment

While the North American Soccer League never turned soccer into a religion in the U.S. and was not without its own race issues – not least the gap in wages between predominantly European elite players and cheaper African and Caribbean players – it nonetheless leaves a legacy of diversity in U.S. soccer that continues today.

As soccer author Ian Plenderleith has argued, the NASL was the first soccer experiment of “mixing several ethnic backgrounds” into one team.![]()

John M Sloop, Professor of Communication Studies, Vanderbilt University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.