By Maura Ives, Texas A&M University, The Conversation

Clement Clarke Moore’s 1823 poem “Account of a Visit from St. Nicholas” redefined Christmas in America. As historian Steven Nissenbaum explains in “The Battle for Christmas,” Moore’s secular St. Nick weakened the holiday’s religious associations, transforming it into a familial celebration that culminated in Santa Claus’ toy deliveries on Christmas Eve.

Nineteenth-century writers, journalists and artists were quick to fill in details about Santa that Moore’s poem left out: a toy workshop, a home at the North Pole and a naughty-or-nice list. They also decided that Santa Claus wasn’t a bachelor; he was married to Mrs. Claus.

Yet scholars tend to overlook the evolution of Santa Claus’ spouse. You’ll see brief references to a handful of late-19th-century Mrs. Claus poems – especially Katharine Lee Bates’ 1888 “Goody Santa Claus on a Sleigh Ride.”

But as I discovered when I began work on a class about Christmas in literature, the writers who created Mrs. Claus were not just interested in filling in the blanks of Santa’s personal life. The poems and stories about Mrs. Claus that appeared in newspapers and popular periodicals spoke to women’s central role in the Christmas holiday. The character also provided a canvas to explore contemporary debates about gender and politics.

The hardest-working woman in the North Pole

Christmas in 19th-century America depended on women’s time and labor: Women prepared family celebrations, organized community and church events and worked in industries that fed seasonal demand for cards, toys and clothing.

This work was both essential and, at times, exhausting: As the century drew to a close, the Ladies’ Home Journal urged its readers not to “tire themselves out preparing for Christmas.”

Many literary depictions of Mrs. Claus paid tribute to the long hours, practical know-how and managerial skills that women’s holiday preparations required.

Sara Conant’s 1875 short story “Mr. and Mrs. Santa Claus,” which appeared in an 1875 issue of Western Rural: Weekly Journal for the Farm & Fireside, celebrated these efforts by describing Mrs. Claus working alongside women across America as they cooked, cleaned and sewed. In Ada Shelton’s 1885 story “In Santa Claus Land,” Santa acknowledged his debt to Mrs. Claus: Without her hard work, he could “never get through” the Christmas season.

But on Christmas Eve, Mrs. Claus hit the North Pole’s glass ceiling.

For Conant, Mrs. Claus was as “indispensible” as Santa, an equal partner in the “joint work” of preparing for holiday festivities. Still, in most Mrs. Claus literature, Santa traveled the world filling stockings while Mrs. Claus stayed home to await his return. In 1884’s “Mrs. Santa Claus Asserts Herself,” Sarah J. Burke’s tearful Mrs. Claus, ignored by Santa and his fans, is left to “cower alone” clasping the fingers she’d “worked to the bone” as Santa speeds off on his sleigh.

A few writers did, however, reward Mrs. Claus’ hard work with a sleigh ride of her own.

Georgia Grey’s 1874 short story “Mrs. Santa Claus’s Ride” allows Mrs. Claus to venture out alone, but only after Santa – adamantly “not a woman’s rights man” – makes her promise to remain unseen. To avoid questioning Santa’s authority or the belief that women belonged at home, the anonymous author of the 1880 tale “Mrs. Santa Claus’s Christmas-Eve” manufactures an emergency: Santa has taken off without some dolls, so Mrs. Claus must saddle Blitzen and deliver them.

Mrs. Claus on the naughty list

Other writers were less willing to allow Mrs. Claus to step outside the home.

Negative representations of her Christmas Eve travels reflected backlash against women’s demands for independence and the vote. The majority of Mrs. Claus writing took place after the Civil War, alongside state and national efforts to grant voting rights to women.

Publications geared toward women didn’t necessarily advocate for more rights and political power. In 1871, the popular woman’s magazine Godey’s Lady’s Book published an anti-suffrage petition addressed to Congress and signed by a number of prominent women, with Godey’s female editor, Sarah Hale, encouraging readers to collect additional signatures. Like Georgia Grey’s Santa, the petition argued that women’s place was in the home, not in public.

Charles S. Dickinson’s “Mrs. Santa Claus’s Adventure,” which appeared in the Dec. 1, 1871, issue of Wood’s Household Magazine, offered a cautionary tale for disobedient wives. Refusing to believe that some children were too naughty to visit, Mrs. Claus trades places with Santa on Christmas Eve. But when she attempts to climb down chimneys to deliver gifts, she is attacked by “hateful imps” that embody children’s “naughty words and deeds.” Depicting Mrs. Claus’ advocacy for children as unrealistic and naive, Dickinson echoes anti-suffrage arguments that emphasized the dangers awaiting women who abandoned the home.

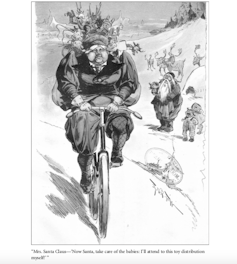

Judge

M.B. Horton’s “A New Departure” took its title from the National Woman Suffrage Association’s failed strategy to register women voters. The 1879 story – published, like the anti-suffrage petition, in Godey’s Lady’s Book – discredits women’s rights activists through its negative portrayal of Mrs. Claus, called “Mrs. St. Nicholas” in this telling.

Jealous of Santa’s fame, Mrs. St. Nick tries to deliver gifts in his place, but her plot to usurp Santa’s role as gift-giver fails when Santa tricks her into delivering a sack of worthless, embarrassing goods.

Mrs. Claus seems an unlikely target of anti-suffrage propaganda, but her association with the ultimate domestic holiday made the idea of an independent Mrs. Claus especially shocking.

‘Goody Santa Claus’ takes the reins

Nineteenth-century writing about Mrs. Claus focused primarily on her work ethic and whether that work would ever allow her a share of Santa’s Christmas limelight.

But scholar and suffragist Katharine Lee Bates, best known as the author of “America the Beautiful,” took a different tack: She gave Mrs. Claus a voice and personality of her own.

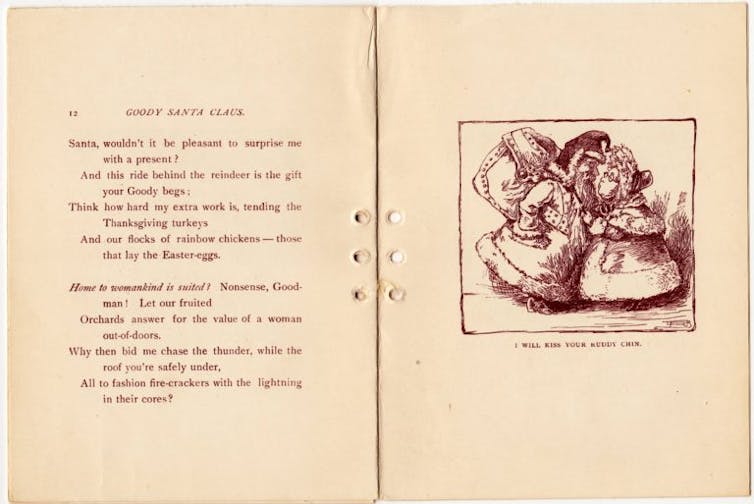

Drawing upon elements of previous Mrs. Claus literature, Bates’ “Goody Santa Claus on A Sleigh Ride” creates an outspoken Mrs. Claus who loves her work and her husband – and is not about to be left behind when Santa makes his deliveries.

Like Burke’s despondent Mrs. Claus, Bates’ Claus – whose title, Goody, stands in for “Mrs.” – begins her monologue with a question: Why does Santa get “all the glory” while she has “nothing but work”?

“Goody Santa Claus on a Sleigh-Ride” first appeared in the children’s periodical Wide Awake. While the illustrations cast Mrs. Claus as affectionate, grandmotherly and nonthreatening, Bates’ text reveals the powerhouse behind Goody’s meek exterior.

Most Mrs. Claus literature highlights her domesticity, but Bates’ Goody is equally adept at housework and outdoor chores. As Santa snacks on Christmas treats and relaxes by the fire, Goody tends Christmas trees, an orchard and toy-growing plants; she also raises livestock and takes on the risky-sounding task of chasing thunder to “fashion fire-crackers with the lightning.”

Although Santa allows Goody to ride beside him, her North Pole work resume isn’t enough to convince him that she has enough “brain” to fill a stocking, and he fears that seeing her climb a chimney would “give his nerves a shock.” Left alone on the rooftop while Santa does his work, Mrs. Claus is on the outside looking in as she peers through the skylight.

But the holes in a poor child’s Christmas stocking stop Santa in his tracks: Sewing was Mrs. Claus’ department. Seizing her chance to shine, Goody mends the sock, proving the value of women’s work and breaking Santa’s rules about chimney-climbing and stocking-filling in the process.

The themes and plots of 19th-century Mrs. Claus writing – including stealth sleigh rides – reappear in Mrs. Claus narratives to this day, and for good reason. Katharine Bates’ thunder-chasing, bonnet-wearing, sweet-talking Goody – and the many Mrs. Clauses who came before her – still speak to every woman who has ever dreamed of a little rest, a little recognition and a seat in the sleigh.

Maura Ives, Professor of English, Texas A&M University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.