CLEVELAND (AP) — Jim Brown was both extraordinary and extraordinarily complicated.

One man. Many versions.

His greatness on the football field is beyond reproach. For generations, Brown, who died Thursday night peacefully at his home in Los Angeles, has long been the standard of excellence for running backs, a freakish blend of brute power and blazing speed who in many ways changed the NFL forever.

Cleveland’s No. 32 is in a class by himself.

“He’s (No.) 1,” said Hall of Famer Emmitt Smith, the league’s career rushing leader. ”(Walter) Payton, two. I fall three.”

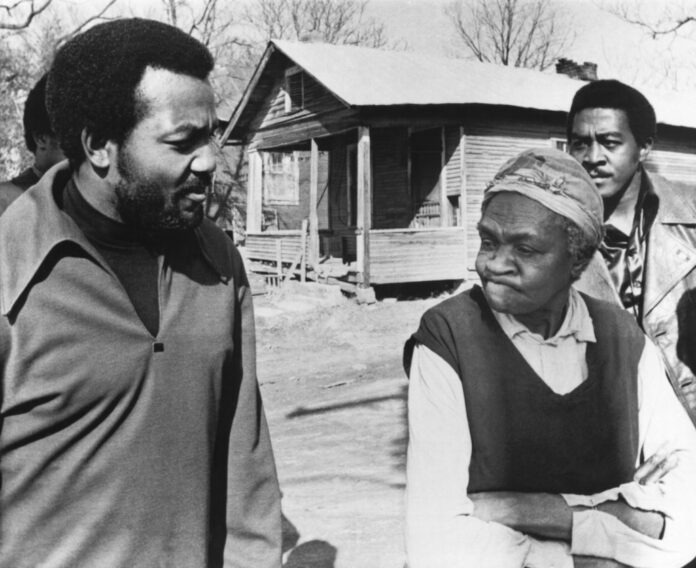

But there is so much more than broken tackles and shattered records to Brown, who walked away from the game at his physical peak to pursue a film career, helping break barriers in Hollywood for Black actors.

There’s the social activist and civil rights champion who used his platform to promote change during one of the most turbulent decades in U.S. history.

And there’s a much less flattering personal side to Brown, who was accused of domestic violence during a time when women’s cries for help were often completely ignored or muted.

Although he was arrested more than a half-dozen times, Brown was never convicted of a serious crime as many of his accusers refused to testify or he was cleared in court. Those transgressions, however, tarnished his image and made it tough for even the most loyal Browns fans to support him.

As a football player, he was nearly flawless.

An All-American at Syracuse, where he also starred in lacrosse, the 6-foot-2, 230-pound Brown, born in Georgia and raised on Long Island, was nothing like the NFL had ever seen when he burst on the scene in 1957.

Flattening tacklers with a deadly stiff arm, making them miss with a stutter step or simply outrunning them, he led the league in rushing as a rookie. He didn’t stop there.

Over the next eight seasons, Brown racked up 12,312 yards rushing, scored 126 touchdowns and averaged 5.2 yards per carry. Despite playing in just 118 games — he never missed one — he still ranks among career leaders in average (third), rushing TDs (sixth) and rushing yards (11th).

But perhaps more significantly, Brown, who ran for a career-high 1,863 yards in 1963, became a sports symbol of Black excellence.

“Jim Brown really represented achievement for the Black community and he was so good that it didn’t matter what color they were, they had to acknowledge him as the best in his field,” NBA superstar Kareem Abdul-Jabbar said. “And that meant a lot to Black Americans in the 60s when anything that any Black person achieved was questioned.

“There were no question marks about Jim Brown.”

Those would come later.

After he rushed for 1,544 yards, scored 17 TDs and won his third league MVP in 1965, Brown retired, informing the Browns while on the set of “The Dirty Dozen” in England. While his decision stunned the team and shocked sports world, it was vintage Brown.

He always did things his way.

During an era when athletes, especially Black athletes, were reluctant to speak their minds for fear of backlash or worse, Brown stepped forward.

While he was still playing, Brown founded the Negro Industrial and Economic Union, an organization focused on creating jobs and supporting Black entrepreneurs.

In 1967, Brown invited some of the nation’s top Black athletes, including Boston Celtics star Bill Russell and Lew Alcindor (later to be known as Abdul-Jabbar), to the Economic Union office in Cleveland to support Muhammad Ali, who had been stripped of his title for refusing to be drafted in protest of the Vietnam War.

It was that sense of power, fearlessness that drove Brown and empowered generations that followed.

“I hope every Black athlete takes the time to educate themselves about this incredible man and what he did to change all of our lives,” LeBron James posted shortly after Brown’s death. ”We all stand on your shoulders Jim Brown. If you grew up in Northeast Ohio and were Black, Jim Brown was a God.”

James has emulated Brown, perhaps more than any other star athlete in the past 60 years. Growing up in Northeast Ohio, he learned about Jim Brown the football player before recognizing there was so much more to him.

“I really just thought of him as the greatest Cleveland Brown to ever play,” James wrote on his Instagram page. “Then I started my own journey as a professional athlete and realized what he did socially was his true greatness. When I choose to speak out, I always think about Jim Brown. I can only speak because Jim broke down those walls for me.”

As he readied for the opening tip of Game 3 in the 2015 NBA Finals in Cleveland, James noticed Brown sitting in a courtside seat. He turned toward the football icon, placed his hands together and bowed in respect, only to have Brown nod in return.

One year later, the two legends stood side by side on a stage after the Cavaliers ended the city’s 52-year championship drought. Brown handed James the Larry O’Brien Trophy in a symbolic passing of the torch.

He had already given him everything else.