By Shawn Smith-Hill, Contributing Writer

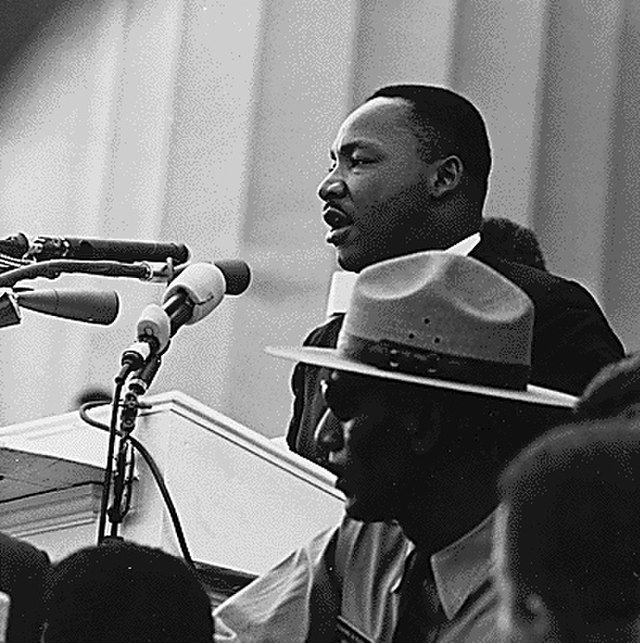

In a landmark speech delivered at Riverside Church in New York City on April 4, 1967, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. took a bold step, intertwining his personal opposition to the Vietnam War with the ongoing struggle for civil rights in the United States. The fusion of two distinct public issues sparked intense reactions with critics arguing that it risked doing a disservice to both causes.

The reactions were swift and varied. Some 168 major publications at the time, including The New York Times, criticized the speech with a harsh verdict. During a time when the U.S. was already under scrutiny for its actions in the war, King’s call to stop aggressions was seen as anti-patriotic by many. The Washington Post went as far as declaring, “He has diminished his usefulness to his cause, to his country and to his people.” The Johnson White House distanced itself from King, leading to a strained relationship.

Critics argued that the moral issues in Vietnam were less clear cut than Dr. King suggested, and they questioned the political strategy of uniting the peace movement and the civil rights movement. A 1967 New York Times editorial entitled “Dr. King’s Error,” expressed similar concerns.

King’s disapproval of the methods used by U.S. forces during the war outlined a growing sense of despair and lack of morals as the media continued to broadcast the war. Dr. King’s assertion that the Vietnam War hindered social progress in the United States and obstructed the path to equality for African Americans remains a controversial stance. The speech drew a connection between the futility of the war and the barriers to achieving justice and equality for minority communities in America.

As the world grapples with ongoing wars and conflicts, Dr. King’s speech holds contemporary relevance. The intersection of war and social justice remains a pressing concern globally. In today’s climate, where conflicts persist and calls for justice reverberate, Dr. King’s legacy extends beyond his iconic civil rights activism and “I Have a Dream” message.

The reactions to Dr. King’s Vietnam speech highlight the challenges of addressing both domestic civil rights issues and international conflicts. As we reflect on this pivotal moment in history, the speech prompts us to consider the complexities of activism, the consequences of merging disparate causes, and the enduring impact of Dr. King’s legacy on social justice movements worldwide.

___

“Over the past two years, as I have moved to break the betrayal of my own silences and to speak from the burning of my own heart, as I have called for radical departures from the destruction of Vietnam, many persons have questioned me about the wisdom of my path. At the heart of their concerns this query has often loomed large and loud: “Why are you speaking about the war, Dr. King?” “Why are you joining the voices of dissent?” “Peace and civil rights don’t mix,” they say. “Aren’t you hurting the cause of your people,” they ask? And when I hear them, though I often understand the source of their concern, I am nevertheless greatly saddened, for such questions mean that the inquirers have not really known me, my commitment or my calling. Indeed, their questions suggest that they do not know the world in which they live.

In the light of such tragic misunderstanding, I deem it of signal importance to try to state clearly, and I trust concisely, why I believe that the path from Dexter Avenue Baptist Church — the church in Montgomery, Alabama, where I began my pastorate — leads clearly to this sanctuary tonight.

I come to this platform tonight to make a passionate plea to my beloved nation. This speech is not addressed to Hanoi or to the National Liberation Front. It is not addressed to China or to Russia. Nor is it an attempt to overlook the ambiguity of the total situation and the need for a collective solution to the tragedy of Vietnam. Neither is it an attempt to make North Vietnam or the National Liberation Front paragons of virtue, nor to overlook the role they must play in the successful resolution of the problem. While they both may have justifiable reasons to be suspicious of the good faith of the United States, life and history give eloquent testimony to the fact that conflicts are never resolved without trustful give and take on both sides.”

___

“I am convinced that if we are to get on the right side of the world revolution, we as a nation must undergo a radical revolution of values. We must rapidly begin the shift from a ‘thing-oriented’ society to a ‘person-oriented’ society. When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, materialism, and militarism are incapable of being conquered.”

“A true revolution of values will soon cause us to question the fairness and justice of many of our past and present policies. On the one hand, we are called to play the Good Samaritan on life’s roadside, but that will be only an initial act. One day we must come to see that the whole Jericho Road must be transformed so that men and women will not be constantly beaten and robbed as they make their journey on life’s highway. True compassion is more than flinging a coin to a beggar. It comes to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring.”

SOURCE: Martin Luther King, Jr. Beyond Vietnam — A Time to Break Silence, delivered 4 April 1967, Riverside Church, New York City, American Rhetoric Online Speech Bank.