By Sylvie Corbet and Jonathan Paye-Layleh, Associated Press

A former Liberian rebel went on trial Monday in Paris on charges of crimes against humanity, torture and acts of barbarism during the West African country’s civil war in the 1990s.

Kunti Kamara, 47, is accused of “complicity in massive and systematic torture and inhumane acts” against civilians in Liberia’s Lofa county in 1993-1994, as one of the leaders of the Ulimo armed group. He was then less than 20 years old.

Kamara, who faces life in prison, denied committing such acts.

“I’m innocent,” Kamara told the court Monday, adding that he doesn’t know any of the witnesses accusing him.

Kamara was arrested near Paris in 2018, following a complaint filed by Swiss-based group Civitas Maxima, specialized in helping victims of crimes against humanity.

During the investigation, he acknowledged having been a battlefield commander, leading about 80 soldiers during the civil war — a choice he said he made to defend himself against Charles Taylor’s rival faction.

According to court documents, he is being accused of having hit a man and then opened his chest with an ax in order to extract and eat his heart. He is also accused of having allowed and abetted, in his position of authority, rapes and sexual torture, and of having compelled people into forced labor under inhumane conditions.

The trial by the Paris criminal court has been made possible under a French law that recognizes universal jurisdiction for crimes against humanity and acts of torture.

Kamara said he left Liberia after the end of the first civil war in 1997 and later went to the Netherlands, then Belgium before coming to France about two years before he was arrested.

Rights groups hailed the trial as an important step to bring justice to victims.

It is “a victory for Liberian victims and a warning to perpetrators that no matter where they are, we’re going to make sure they’re held accountable for the crimes they committed in Liberia,” Hassan Bility, head of the Global Justice and Research Project, told The Associated Press. Bility’s nongovernmental organization is dedicated to the documentation of wartime atrocities in Liberia and to assisting victims in their pursuit of justice.

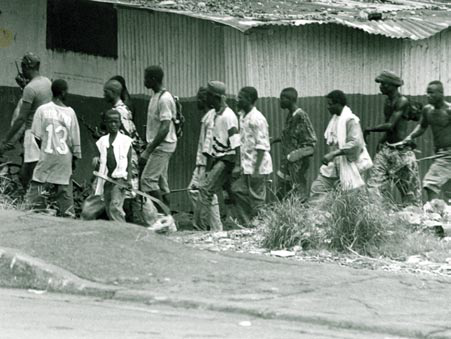

Human Rights Watch and the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) stressed that Liberia’s first civil war was especially marked by “violence against civilians, as warring factions massacred and raped civilians, pillaged, and forced children to kill and fight.”

Elise Keppler, associate international justice director at Human Rights Watch, said the trial is especially important due to “the failure of Liberian authorities to hold to account those responsible for serious crimes during the civil wars.”

“France’s trial for atrocities in Liberia reinforces the importance of the principle of universal jurisdiction to ensure that the worst crimes do not go unpunished,” said Clémence Bectarte, a lawyer who coordinates FIDH’s Litigation Action Group.

Liberia’s back-to-back civil wars killed an estimated 250,000 people between 1989 and 2003.

The country’s post-war truth and reconciliation commission in 2009 recommended prosecution for dozens of ex-warlords and their commanders bearing greatest responsibilities for the war. But successive governments have largely ignored the recommendations, much to the disappointment and frustration of war victims.

Political analysts say this is largely because some key players in the war have occupied influential positions in government, including in the legislature, since the end of the war nearly 30 years ago.

The current president, George Weah, spoke against impunity for war crimes when he was in opposition, but has shown reluctance to respond to citizens’ calls for the establishment of a war crimes court.

During her visit to Liberia last week, the U.S. ambassador on war crimes, Dr. Beth Van Schaack, promised her government would “100%” support Liberia if the country decided to establish a court to look into its past.

Expressing disappointment that Liberia is still lagging behind in fostering transitional justice, she assured Liberians she will recommend “that if something starts to move, that we should be a partner in that effort.”

The Paris trial, scheduled to last four weeks, is the fifth dealing with crimes against humanity and torture in France. Previous cases concerned crimes related to the 1994 genocide in Rwanda.

___