By

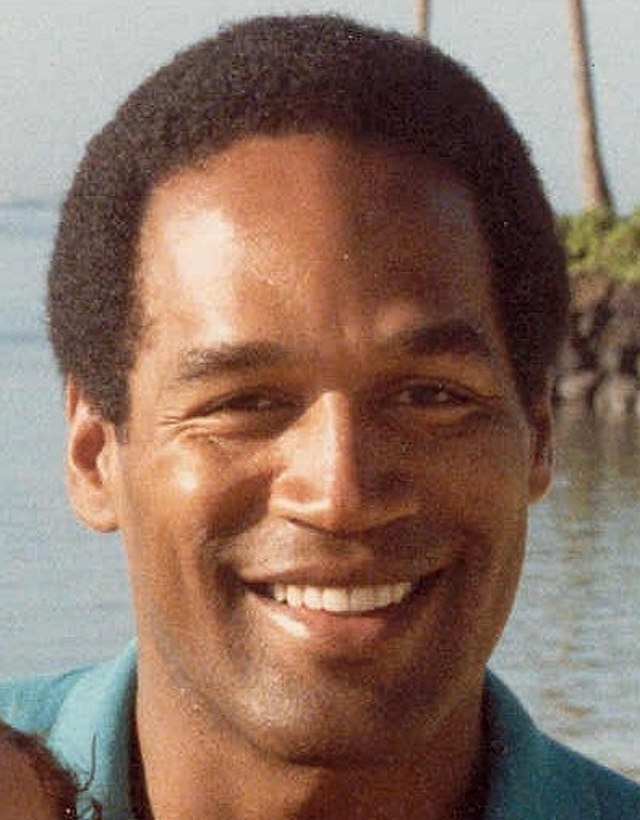

O.J. Simpson, who parlayed a legendary, record-setting pro football career into pop culture superstardom — then saw it all crumble when he stood accused of brutally murdering his ex-wife in a riveting trial that reflected America’s deep racial divide — died of cancer Thursday.

Simpson, 76, announced he had been diagnosed with prostate cancer two months ago, according to the National Football League Hall of Fame. It is not known where Simpson died.

By turns a football hero, sportscaster, rental-car pitchman, and star of the cult-classic “Naked Gun” comedy movies, Simpson had a classic American rags-to-riches success story, rising from poverty to the NFL Football Hall of Fame. But his achievements will be forever overshadowed by the first-degree murder charges he faced for the grisly 1994 killings of Nicole Brown Simpson and her friend, Ronald Goldman, in Los Angeles’ posh Brentwood neighborhood.

A jury ultimately acquitted Simpson in a trial that underscored the nation’s racial divisions — a Black sports icon was cleared of killing his young blonde ex-wife in a murder that had the hallmarks of a crime of passion. But it was the biggest bombshell in a series of headline-grabbing incidents that destroyed Simpson’s all-American image and forever tarnished his football legacy.

Coming just two years after the Rodney King beating and uprisings, what some called the Trial of the Century transformed Simpson from a global celebrity into a Rorschach test of Americans’ opinions about a two-tiered justice system that typically favors the wealthy, white, and powerful.

Broadcast live for days on end, the trial elevated key players — Johnnie Cochran, Robert Kardashian, Marcia Clark, Christopher Darden, and Kato Kalen — into household names. And the verdict, which outraged white people but spurred cheers in Black neighborhoods, forced whites to acknowledge problems in the justice system that Black people always knew were there.

A year after his 1996 acquittal, the victims’ families sued Simpson for the killings in civil court, winning $33.5 million in damages.

A decade later, however, Simpson sold a book manuscript, “If I Did It,” and a prospective TV interview, describing — hypothetically — how the murders he denied committing could have been carried out. Overwhelming backlash, led by the murder victims’ families, scuttled the project, but the Goldman family bought the book rights and rewrote it to suggest Simpson had gotten away with murder.

Then, in 2007, Simpson was arrested and charged with the gunpoint robbery of a sports memorabilia dealer in a Las Vegas hotel room. Simpson denied being armed and said he just wanted to retrieve some of his personal artifacts that had been stolen, but a jury disagreed. Simpson was sentenced to 9 to 33 years in prison but was granted parole after serving minimum time.

After his release, Simpson moved to Florida and kept a low profile, but his meteoric rise and Shakespearean downfall inspired dozens of tell-all books, documentaries, and TV series. At the same time, a mostly-Black jury’s acquittal of a Black sports hero accused of killing a white woman also triggered thorny questions about what justice means in America.

Difficult Early Life

Born Orenthal James Simpson on July 9, 1947, O.J. grew up poor in the hardscrabble majority-Black housing projects of San Francisco’s Potrero Hill, a now-gentrified enclave that was rife with crime and gangs in the 1940s and 50s. Afflicted with rickets, a bone disease caused by vitamin D deficiency, Simpson wore home-made leg braces as a child, but he overcame the disease, developing into a talented athlete.

With an absent father and a mother working hard to put food on the table, Simpson wasn’t able to overcome the influence of his surroundings, joining the Persian Warriors street gang and developing a reputation as a neighborhood tough. He was repeatedly suspended from school for troublemaking, and was no stranger to violence.

“I was in a lot of street fights,” he recalled later. “Maybe because I usually won.”

Unable to win a football scholarship coming out of high school, Simpson enrolled in City College of San Francisco, where he smashed several records and had a late growth spurt, sprouting to 6 feet 1 inch. His raw combination of power and speed won him a scholarship to the University of Southern California, then a college football juggernaut.

After establishing himself as a starter, Simpson thrilled the Trojan faithful with an electrifying, fluid ball-carrying style that broke NCAA records. He earned All-America honors and won the Heisman Trophy, the sport’s highest award, in 1968.

Drafted by the Buffalo Bills in the first round of the 1969 NFL draft, Simpson would go on to play in the league for 11 years, breaking the league’s single-season rushing record in 1973. Nicknamed “The Juice,” a play on his initials, Simpson was among the first league-wide superstars of the NFL’s modern era, and was selected to the Hall of Fame the first year he was eligible.

When his career ended in 1979, Simpson — handsome, telegenic, and coast-to-coast famous — seamlessly transitioned from the locker room to the broadcast booth and Hollywood soundstage. He was a pro football analyst for ABC and NBC, became the face of Hertz car rental in a series of memorable ads featuring him running through airports, and embarked on a marginally successful movie career.

Through it all, Simpson carefully cultivated an image of a nice, articulate, non-threatening Black American idol, a racially transcendent star who was trusted by and marketable to both Black and white audiences.

“I’m not Black, I’m O.J.,” he reportedly liked to tell friends.

But trouble roiled just under the surface of his undeniably successful life.

Tumultuous Marriages

Though they’d met in high school and married in 1967, Simpson and his first wife, Marguerite Whitley, had a marriage punctuated by several separations starting in 1970, the year after he entered the NFL. They parted for good in 1979, not long after their 23-month-old son, Aaren, drowned in the family swimming pool.

Around that time, Simpson met Nicole Brown, a young waitress with blonde, movie-star looks who worked at a nightclub near Simpson’s home; at the time, he was 30 and she was 18. After Simpson’s divorce from his first wife, Simpson and Brown began dating and were married in 1985. The couple had two children.

Their marriage, however, was marked by frequent reports of domestic violence; Los Angeles police logged multiple calls in which Brown Simpson dialed 911, seeking protection from her enraged husband. In January 1989, police arrived to find Brown Simpson — her face battered, wearing only sweatpants and a bra — hiding in bushes outside the couple’s home.

Officers did not arrest Simpson at the scene, but he was fined and placed on probation after pleading guilty to spousal battery. The couple divorced in 1992, but Simpson continued to confront his ex-wife, who kept calling police.

On June 12, 1994, Brown Simpson, 35, and Goldman, 25, were attacked outside her condominium in Brentwood, not far from her ex-husband’s estate. Police said Brown Simpson was nearly decapitated, and Goldman had been hacked to death.

Police zeroed in on the former football hero and arranged for him to surrender five days after Brown Simpson’s funeral. But Simpson fled instead, leading a squadron of officers and news helicopters on the infamous, low-speed, 60-mile chase along the Interstate 5 freeway in Southern California. His friend and former teammate, Al Cowling, was at the wheel of the white Ford Bronco.

Simpson, distraught and reportedly suicidal, was arrested when he returned home after the chase and booked for first-degree murder.

Sports Hero On Trial

The trial was a 9-week spectacle that unfolded before a 12-person jury — 10 of whom were Black. Though they had substantial evidence, including hair, fibers, and blood, police never found the murder weapon, and no eyewitnesses. Meanwhile, the defense, led by Cochran, insinuated to the jury that Simpson was the victim of a racist police department intent on taking down a powerful Black man. The jury agreed.

The highly-anticipated verdict, broadcast live around the nation, created a split-screen image of America: Black people — thrilled that a Black man finally beat the criminal justice system — cheered. Whites, convinced of his guilt, were stunned and outraged that Simpson walked free.

Ultimately, Simpson died a free man, but was not able to outrun his past.