by

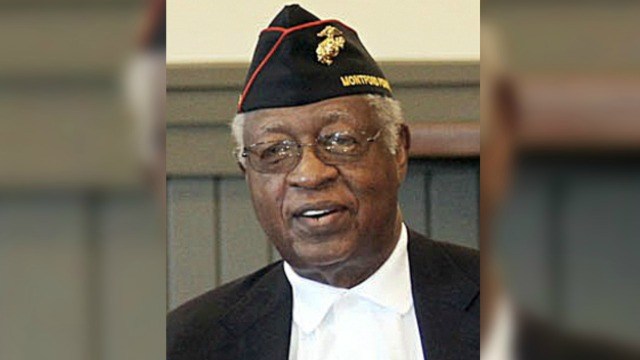

A Georgia man who served among the first black U.S. Marines during World War II died Tuesday just a few years after Congress honored him and fellow Montford Point Marines for their pioneering role in a segregated military.

Angus Hardie Jamerson, known as Jay to his family and friends, died peacefully in his sleep at age 89, said his daughter, Wendy Jamerson. He lived in Villa Rica, 35 miles west of Atlanta, and would have celebrated his 90th birthday later this month.

Jamerson was a student at Morehouse College in Atlanta when he was drafted in 1945 and sent to Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. That’s where Montford Point, a segregated training facility, had been established in 1942 after President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered the Marine Corps to begin accepting black recruits.

Jamerson would recall stepping off a bus into a mosquito-infested camp where trainees lived in crude wooden huts and were often subjected to cruder behavior, his wife, Doris Jamerson, said. On their first day, she said, Jamerson and fellow black recruits were slapped across the face by a white instructor. Throughout their service, the black Marines were barred from setting foot onto neighboring Camp Lejeune without a white escort.

Jamerson’s service lasted about 18 months, most of it spent performing postal duties. After leaving the Marines in 1946, he graduated from Morehouse and later earned a law degree while living in California. He returned to the Atlanta area in 1979 after starting a cosmetics company.

“He started out wanting to serve and ended up making a historical difference,” his wife said. “But he had no idea of the significance of it at all.”

Neither did most Americans. Unlike the Tuskegee Airmen during World War II and the Army’s Buffalo Soldiers formed after the Civil War, blacks who served in the Montford Point Marines received scant recognition for decades. It’s estimated 20,000 of them trained from 1942 until 1949, when the Marine Corps was ordered to desegregate.

Fred Codes said he had served in the Marines for a decade before he first heard of Montford Point in the 1980s. Now Codes serves as Southern regional vice president for the National Montford Point Marine Association.

“They actually fought for the right to fight,” said Codes, who counted Jamerson among the members of the group’s Atlanta chapter. “The history was really, really buried.”

That changed somewhat in 2011 when U.S. lawmakers voted to award the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest civilian honor given by Congress, to the surviving Montford Point Marines. Codes said his group estimates only about 300 of them are still living, and their numbers are rapidly declining.

Jamerson was among 15 Montford Point veterans in the association’s Atlanta chapter to accept the medal at a banquet four years ago, Codes said. After Jamerson’s death, only nine remain.

Wendy Jamerson said her father didn’t know about the congressional award until he read about it in the newspaper. She said he appeared nonchalant, telling her: “Well, you know, they’re going to give me a medal.”

But Jamerson’s pride was unmistakable.

“He did sleep with it for a couple of nights,” his wife said. “We couldn’t get it off him.”