(CNN) — The genesis of photographer Joy Gregory’s latest project, “Shining Lights,” began 40 years ago, at a Valentine’s Day party in London. It was here that Joy, who was the first Black woman to study an MA in Photography at the Royal College of Art in London, first met activist and writer Araba Mercer. After the party and as they became friends, Mercer suggested the pair collaborate on a book about women’s photography.

“I knew lots of photographers who were emerging at that time,” Gregory recalled over tea in a cafe near her studio in south London. “So I persuaded all of the people I knew to submit work.” They presented their plan for the book — comprising the photographs gathered by Gregory, and text by Mercer — to Sheba, a feminist publishing collective focused on Black women’s storytelling that Mercer was a key member of. Sheba was enthusiastic, but the cost of printing all the submitted photographs ultimately proved prohibitive.

The idea then, for a book surveying the work of Black women’s photography in Britain in the 1980s and 1990s, lay dormant for several decades. But a 2019 talk Gregory gave at Autograph gallery in London about photographer Maxine Walker’s work sparked renewed interest in the contribution of women of color to photographic art during this period.

The result is “Shining Lights: Black Women Photographers in 1980s–90s Britain,” a new photography book edited by Gregory and co-published by Autograph and Mack. Divided into thematic chapters exploring community and activism, kinship and family ties, travel and landscape photography and more, “Shining Lights” features 57 photographers, capturing the rich breadth of work from this overlooked period and community.

Telliing the stories no-one else was

The book includes work by well-known artists such as Walker, whose photographic practice centres on representations of Black womanhood, surrealist artist Mona Hatoum, and Turner Prize nominee Ingrid Pollard, whose images in the book use portraiture to examine gender and sexuality.

As well as casting the work of these artists in a new light, the project also introduces readers to photographers working during that time who are perhaps not as well known. Examples include Jacqueline Moran Daubercies, whose vibrant photographic practice focused on Latin American women and children, and Maria Pedro, whose poised self-portraits in the book reimagine herself as historical Black female royalty.

“What’s really interesting about history, and the way that history is recorded, is there’s always heroes, but actually, it was a collective,” Gregory told CNN in an interview. “And I think a lot of the collective has been written out of the history.”

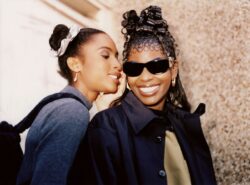

Mandatory Credit: Courtesy the artist/MACK // CNN

“Shining Lights” then is Gregory’s considered effort to write in that missing history. Reconnecting with old networks and contacts to gather the material for the book was a meticulous task, with Gregory posting callouts in her own Facebook group as well as others and spreading the word around different creative networks.

She says that while some of the book’s contributors are now recognizable photographers, others have moved on entirely from photography since that era. Some had forgotten or not revisited their work during the interim decades, or had even lost large portions of their work. Gregory recalls one contributor arriving at her studio with three big bags of undeveloped negatives, consisting of close to 10,000 images. “That’s basically an entire book there, but again, that’s one of the people that’s completely disappeared from view.”

“That was the problem with going back and looking at the magazines and publications that were produced in the 1980s to try and find a trace of the women that are in this book,” said Gregory. “That wasn’t there because they weren’t picked up at that time, and nobody was telling their story.”

For some of the book’s contributors, Gregory says, revisiting that time and the poor treatment they received from the industry was painful. “It was reliving those disappointments…people were traumatized by the experience, and that wasn’t surprising, but it was shocking, in a way.”

An inaccessible medium

This era for Gregory, who was awarded the prestigious Freelands Award in 2023, was foundational. “I think I wouldn’t really have a practice without that period, obviously,” she said. Her own photographic series, “Autoportrait,” features in the book; originally made in 1990, it consists of a series of nine self-portraits of Gregory posed at various angles, looking both directly into and turned away from the camera.

She recalls how those among her network were often shut out of inaccessible arts institutions and forced to work at the margins. “Now, everybody has access to photography with their mobile phone; then it was a much more technically inaccessible medium,” she said.

Often faced with disappointment and rejection, these photographers rallied together. “There was a move to actually educate and help each other, and there was a lot of sharing of materials and knowledge,” she said, adding that community centres played an important role in offering space for learning. Gregory gives one example of photographer and curator Mumtaz Karimjee teaching herself how to do cibachrome color printing, and then teaching others in the network the same skill.

“The way in which people supported each other was really important — well, essential — because the other networks were not open to us,” said Gregory. “I think as women, it wasn’t open, and I think being of color, it definitely wasn’t open.”

In the book, Black “refers to the whole gamut of color, which was really about difference,” says Gregory. “Anybody who was different and seen as outside was included under that title Black, and it was more of a political identity, more than anything else.”

A 1987 essay written by Karimjee and included in the book explains this definition and feeling in more detail. It’s one of several contextual essays and conversations in “Shining Lights,” both from the present day and from the 1980s and 1990s, on themes including the abuse of power in photography, identity in British arts and cultural production, and change and continuity for new generations.

On this note, Gregory feels that in some ways, the landscape today remains similarly inaccessible, meaning that the enterprising, do-it-yourself attitudes of the 1980s and 1990s are still present among new and emerging artists. One example featured in the book is photographer and filmmaker Ronan Mckenzie, who established her own independent exhibition space, HOME, in London in 2020.

“I feel that a lot of the issues that we were dealing with in the 1980s haven’t gone away, and I think to include those essays actually highlights that,” said Gregory, adding that she hopes it will be encouraging for younger artists to see the work, perspectives and leadership of those who have preceded them.

While Gregory played a vital role in the book’s creation with support from associate editor Taous Dahmani, she emphasizes that it’s more about the dozens of photographers whose work is finally receiving overdue recognition

“The book is women in their own voices,” said Gregory. “That’s what I wanted to bring. So in a way, I feel that this is not my book. This is their book.”

The-CNN-Wire