As tensions grow in Ukraine, Sudan is another important target for expanded Russian influence.

By Joseph Hammond, Zenger News

Brewing war clouds along Russia’s border with Ukraine suggest Moscow is considering a more assertive role in Eastern Europe. Yet, quietly and with little media attention, Russia has also begun reasserting itself in an entirely different corner of the world: Sudan.

It has not lined up troops and tanks on the northeast African country’s borders with Egypt or along the Red Sea across from Saudi Arabia, but Moscow has reportedly amassed an army of social media accounts and the personnel to support them.

“Given changing political realities in Sudan and elsewhere, I expect the government will seek a more balanced approach between Russia and the United States,” says Yasir Zaidan, a lecturer at the National University of Sudan whose research focuses on political transitions in the Red Sea region and Middle Eastern influence in the Horn of Africa.

Port Sudan sits just a few hundred miles north of the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, through which about 9 percent of the world’s crude oil passes. It also lies to the north of Djibouti, the small African state home to military bases from France, the United States, Japan, China, Saudi Arabia and other countries.

In 2020, Russia signed an agreement with Sudan’s government to develop a naval base at Port Sudan. Given this context, Russia’s social media influence campaign has been aimed at ensuring support for its role in the region, discrediting its Western opponents and supporting factions seen working closely with Russia in Sudan, analysts say.

“We removed 83 Facebook accounts, 30 Pages, six Groups and 49 Instagram accounts operated by local nationals in Sudan on behalf of individuals in Russia,” Facebook announced last year. A similar batch of accounts was pulled offline by the social media giant in a bid to curb Russian influence in 2019.

Moscow has long had an interest in the Horn of Africa. In the late 19th century, a group of Russian Cossacks established a brief “New Moscow” in what is today Djibouti. During the Cold War, Russia built strong ties to a number of then communist nations, throwing its heft behind Yemen, Ethiopia and Somalia. Russia also developed an on-and-off-again relationship with Sudan’s leaders.

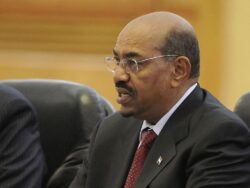

During the 30-year reign of Omar al-Bashir, no country in the region had a more pro-Russian outlook than Sudan. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute’s arms transfer database, weapons from Russia and former Soviet republics such as Belarus and Ukraine made up the vast majority — 77 percent — of Sudanese weapons purchases from 2007 to 2016. As the grip of Bashir’s regime began to relax, Russia’s influence blossomed, analysts say.

In 2017, Bashir asked Russia to protect the country from the United States. That same year, Russia’s ambassador to Sudan mysteriously died while swimming in his pool.

The Wagner Group, a Russian private military company, has reportedly been involved in operations in a number of African countries. Its first intervention came in 2017 under a contract with the Libyan Cement Company. It later helped train Sudanese forces.

Protests that would topple Bashir’s regime within four months began in December 2018. According to French and other Western governments, Russia’s social media campaign in Sudan started as it sought to ensure the survival of the regime.

“Instead of deploying conventional Russian soldiers, Moscow has turned to special operations forces, intelligence units and private military companies (PMCs) like the Wagner Group to do its bidding. Russia’s strategy is straightforward: to undermine U.S. power and increase Moscow’s influence using low-profile, deniable forces like PMCs that can do everything from providing foreign leaders with security to training, advising and assisting partner security forces,” the Center for Strategic and International Studies said in a September 2020 report.

“These campaigns were conducted in a very professional way,” said Mekki El-Megrebbi, a former spokesperson for the Sudanese Embassy in Washington. “There was a sort of public survey effort that went on ahead of the campaign … going out to individual Sudanese claiming to be posters. Some of that data was later collected and used in the campaigns that were launched by [the Russians]. Still despite this serious approach, you could tell that the content was being generated by Syrians or Palestinians sometimes when you read it. Sometimes it’s in the use Arabic and sometimes in the way the argument was presented.”

A former adviser to Sudan’s Ministry of Culture and Information said after the fall of Bashir, the country’s transitional government worked to counter disinformation efforts in the nation, with Russia being a primary concern. In June, it announced a crackdown on social media accounts and hate speech that was in part aimed at battling Russian influence.

A coup that began in October 2021 ended Sudan’s civilian-led transitional government. With little civilian oversight, some analysts worry the government could be turning a blind eye to Russian influence operations.

“It’s possible that such relationships are ongoing security institutions like the Rapid Support Forces have asked for Russian support on social media campaigns,” said Zaidan. “Social media is a difficult thing to control. It could prove a double-edged sword. Just because you’re promoting a narrative doesn’t mean it will emerge victorious. Let’s not forget social media played a role in the fall of the Bashir regime.”

In a June 2021 Middle East Institute report, Giorgio Cafiero, CEO and founder of Gulf State Analytics, a geopolitical risk consultancy, wrote: “What remains uncertain is how much success the U.S. will have convincing post-revolutionary Sudan to scale back its partnership with Russia.”

Edited by Richard Pretorius and Kristen Butler