By Stacy M. Brown (NNPA Newswire Contributor)

Pete Taney knew this day would come.

“I’ve been looking over my shoulders all of my life, so this is no surprise,” said Taney, the lead vocalist, banjo, fiddle and harmonica player for the popular Stroudsburg band, “The Juggernaut String Band.”

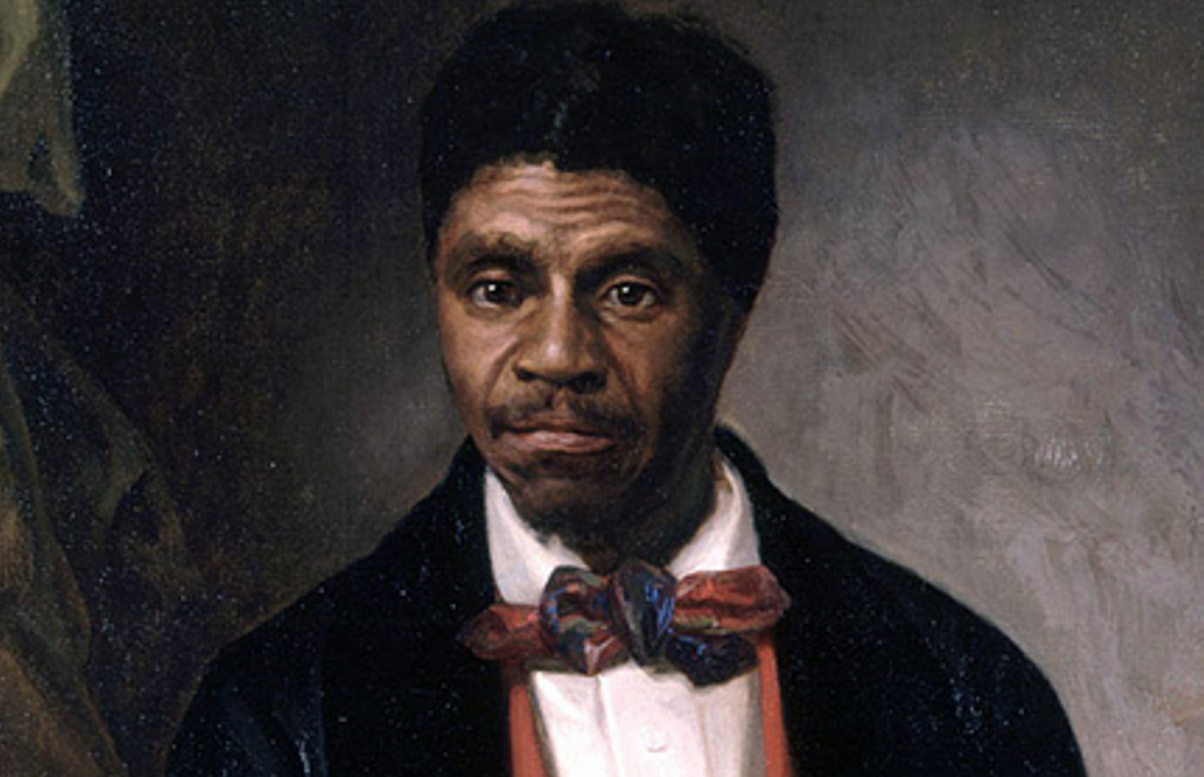

Taney is talking about a published report out of the nation’s capital that detailed recent meetings between his family members, descendants of one-time slave owners, and descendants of Dred Scott, a slave who in 1857 unsuccessfully filed a suit arguing that he and his family should be given their freedom, because they had lived in Illinois and other places where slavery was considered illegal.

Charlie Taney, Pete’s brother, was outside the Maryland State House this week and read some of the words that his great-great-grand uncle, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, wrote in the U.S. Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision 160 years ago:

“Black people cannot be U.S. citizens and have no rights except the ones that White people give them. Whites are superior to Blacks. Slavery is legal.”

Charlie Taney told the reporters that, “You can’t hide from the words that [Roger B.] Taney wrote,” as he stood a few feet from a statue of his ancestor. Roger B. Taney lived in Maryland and was the chief justice of the nation’s highest court from 1836 until his death in 1864. “You can’t run, you can’t hide, you can’t look away,” Charlie Taney said. “You have to face them.”

For Pete Taney, his brother’s words resonated—and it brought back so many memories.

“It wasn’t something that we didn’t talk about,” Pete Taney said on Tuesday. “It was discussed at family dinners all of the time, our history. I’m just so proud of my brother and my niece to be able to stand up [publicly] and do this and take responsibility. I completely agree with them.”

During the event in Maryland earlier this week, Charlie Taney turned to Lynne M. Jackson, the great-great granddaughter of Scott, and apologized—on behalf of his family, to the Scott family and to all African-Americans, for the “terrible injustice of the Dred Scott decision.”

Jackson accepted the apology from her family and “all African-Americans who have the love of God in their heart so that healing can begin.”

Taney asked for a hug, and the two embraced.

Pete Taney said he had been there when the groundwork was first set for such a meeting.

There was a workshop for a one-act play and a taping for a National Public Radio appearance.

“I got to meet Dred Scott’s descendants and it was very emotional, but very wonderful,” Pete Taney said.

Their appearance this week in Annapolis was part of an ongoing reconciliation process, and a push by the descendants of both families to add a statue of Scott near the statue of the late Justice Taney, which activists have sought to remove for years.

While Charlie Taney said the meeting and the statue presents opportunities to learn and a chance to come together and chance to heal a nation—and not to bury the past, Pete Taney said he wholly supports a statue of Scott.

“I believe adding a statue of Dred Scott would create the kind of dialogue that needs to be discussed openly in this country,” Pete Taney said. “Much of the stain on my family’s history needs to be discussed.”

Jackson, a former law firm manager from Missouri and the founder of the Dred Scott Heritage Foundation, told reporters at the gathering that her family also believes that having the statue of the pro-slavery chief justice, along with one of Scott and historical information about the court decision, would be a “learning experience and an educational opportunity.”

“Add to it, don’t take from it,” Jackson said.

Reportedly, a proposal in the Maryland legislature to remove the Taney statue died in committee last year, however. There is no similar bill this year, and some of the activists who in the past have called for the statue’s removal now appear to agree with the Taney and Scott descendants that placing the statue in a more complete historical context would be preferable.

Charlie Taney, an advertising executive who lives in Connecticut, called his great-great-grand-uncle a “complicated man,” but also readily acknowledged that he was a “stone racist.”

It was Charles Taney’s daughter, Kate Billingsley, who wrote “A Man of His Time,” a one-act fictional play about a Taney descendant meeting a Scott descendant. The play, produced in New York last year, brought real descendants of each family together for the first time.

“A Taney bringing an apology to a Scott is like ‘bringing a band aid to an amputation,’” Charlie Taney quoted his daughter as saying on Monday, underscoring what the family says is need for additional dialogue and continued healing.

“An apology is not enough,” he said. “But it is necessary.”

Pete Taney agreed.

“We’ve got to do outreach. This country and its leaders are not doing it but we can,” Pete Taney said. “I’m so proud of my brother and my niece. Our family needs to keep having these important discussions.”