By Alisha Gaines, Florida State University

A peculiar desire seems to still haunt some white people: “I wish I knew what it was like to be Black.”

This wish is different from wanting to cosplay the coolness of Blackness – mimicking style, aping music and parroting vernacular.

This is a presumptive, racially imaginative desire, one that covets not just the rhythm of Black life, but also its blues.

While he doesn’t want to admit it, Canadian-American journalist Sam Forster is one of those white people.

Three years after hearing George Floyd cry “Mama” so desperately that it brought a country out of quarantine, Forster donned a synthetic Afro wig and brown contacts, tinted his eyebrows and smeared his face with CVS-bought Maybelline liquid foundation in the shade of “Mocha.” Though Forster did not achieve a “movie-grade” transformation, he became, in his words, “Believably Black.”

He went on to attempt a racial experiment no one asked for, one that he wrote about in his recently published memoir, “Seven Shoulders: Taxonomizing Racism in Modern America.”

For two weeks in September 2023, Forster pretended to hitchhike on the shoulder of a highway in seven different U.S. cities: Nashville, Tennessee; Atlanta; Birmingham, Alabama; Los Angeles; Las Vegas; Chicago and Detroit. On the first day in town, he would stand on the side of the road as his white self, seeing who, if anyone, would stop and offer him a ride. On the second day, he stuck out his thumb on the same shoulder, but this time in what I’d describe as “mochaface.”

Since September is hot, he set a two-hour limit for his experiments. During his seven white days, he was offered, but did not take, seven rides. On seven subsequent Black days, he was offered, but did not take, one ride. He speculated that day was a fluke.

Forster is not the first white person to center themselves in the discussion of American racism by pretending to be Black.

His wish mirrors that of the white people featured in my 2017 book, “Black for a Day: White Fantasies of Race and Empathy.” The book tells the history of what I call “empathetic racial impersonation,” in which white people indulge in their fantasies of being Black under the guise of empathizing with the Black experience.

To me, these endeavors are futile. They end up reinforcing stereotypes and failing to address systemic racism, while conferring a false sense of racial authority.

Going undercover in the South

The genealogy begins in the late 1940s with Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Ray Sprigle.

Sprigle, a white reporter at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, decided he wanted to experience postwar racism by

“becoming” a Black man. After unsuccessfully trying to darken his skin beyond a tan, Sprigle shaved his head, put on giant glasses and traded his signature, 10-gallon hat for an unassuming cap. For four weeks beginning in May 1948, Sprigle navigated the Jim Crow South as a light-skinned Black man named James Rayel Crawford.

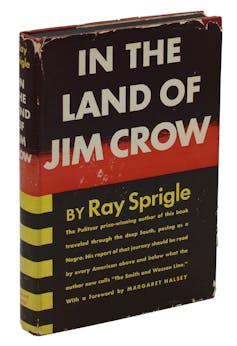

Sprigle documented dilapidated sharecropper’s cabins, segregated schools and women widowed by lynching. What he witnessed – but did not experience – informed his 21-part series of front page articles for the Post-Gazette. He followed up the series by publishing a widely panned 1949 memoir, “In the Land of Jim Crow.”

Sprigle never won that second Pulitzer.

Cosplaying as Black

Sprigle’s more famous successor, John Howard Griffin, published his memoir, “Black Like Me,” in 1961.

Like Sprigle, Griffin explored the South as a temporary Black man, darkening his skin with pills intended to treat vitiligo, a skin disease that causes splotchy losses of pigmentation. He also used stains to even his skin tone and spent time under a tanning lamp.

During his weeks as “Joseph Franklin,” Griffin encountered racism on a number of occasions: White thugs chased him, bus drivers refused to let him disembark to pee, store managers denied him work, closeted, gay white men aggressively hit on him, and otherwise nice-seeming white people grilled him with what Griffin called the “hate stare.” Once Griffin resumed being white and news broke about his racial experiment, his white neighbors from his hometown in Mansfield, Texas, hanged him in effigy.

For his work, Griffin was lauded as an icon in empathy. Since, unlike Sprigle, he experienced racist incidents himself, Griffin showed skeptical white readers what they refused to believe: Racism was real. The book became a bestseller and a movie, and is still included in school curricula – at the expense, I might add, of African-American literature.

Griffin’s importance to this genealogy extends beyond middle-schoolers reading “Black Like Me,” to his successor and mentee, Grace Halsell.

Halsell, a freelance journalist and former staff writer for Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration, decided to “become” a Black woman – first in Harlem in New York City, and then in Mississippi.

Without consulting any Black woman before baking herself caramel in tropical suns and using Griffin’s doctors to administer vitiligo-corrective medication, Halsell initially planned to “be” Black for a year. But after alleging someone attempted to sexually assault her while she was working as a Black domestic worker, Halsell ended her stint as a Black woman early.

Although her experiment only lasted six months, she still claimed to be someone who could authentically represent her “darker sisters” in her 1969 memoir, “Soul Sister.”

Turn-of-the-century ‘race switching’

Forster writes that his 2024 memoir is the “fourth act” – after Sprigle, Griffin and Halsell – of what he calls “journalistic blackface.”

However, he is not, as he claims, “the first person to earnestly cross the color barrier in over half a century.”

In a 174-page book self-described as “gonzo” with only 17 citations, Forster failed to finish his homework.

In 1994, Joshua Solomon, a white college student, medically dyed his skin to “become” a Black man after reading “Black Like Me.” His originally planned, monthlong experiment in Georgia only lasted a few days. But he nonetheless detailed his experiences in an article for The Washington Post and netted an appearance on “The Oprah Winfrey Show.”

Then, in 2006, FX released, “Black. White.,” a six-part reality television series advertised as the “ultimate racial experiment.”

Two families – one white, the other Black – “switched” their races to perform versions of each-otherness while living together in Los Angeles. While the makeup team won a Primetime Emmy Award, the families said goodbye seething with resentment instead of understanding.

A masterclass of white arrogance

Believing it would distract from the findings of his experiment, Forster refuses to show readers his mochaface.

Even after confronting evidence forcing him to question his project’s appropriateness, like the multiple articles condemning “wearing makeup to imitate the appearance of a Black person,” he insists his insights into American racism justify his methods and are different from the harmful legacies of blackface. As he stands on the side of the road, sun and sweat compromising whatever care he took to paint his face, Forster concludes that racism can be divided into two broad taxonomies: institutional and interpersonal.

The former, he believes, “is effectively dead,” and the latter is most often experienced as “shoulder,” like the subtle refusal to pick up a mocha-faced hitchhiker.

Forster’s Amazon book description touts “Seven Shoulders” as “the most important book on American race relations that has ever been written.”

Indeed, it is a masterclass – but one on the arrogance of white assumptions about Blackness.

To believe that the richness of Black identity can be understood through a temporary costume trivializes the lifelong trauma of racism. It turns the complexity of Black life into a stunt.

Whether it’s Forster’s premise that Black people are ill-equipped to testify about their own experiences, his sketchy citations, the hubris of his caricature or the venom with which he speaks about the Black Lives Matter movement, Forster offers an important reminder that liberation can’t be bought at the drugstore.![]()

Alisha Gaines, Associate Professor of English, Florida State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.