By BILL BARROW, Associated Press

ATLANTA (AP) — Raphael Warnock is the first Black U.S. senator from Georgia, having broken the color barrier for one of the original 13 states with a special election victory in January 2021, almost 245 years after the nation’s founding.

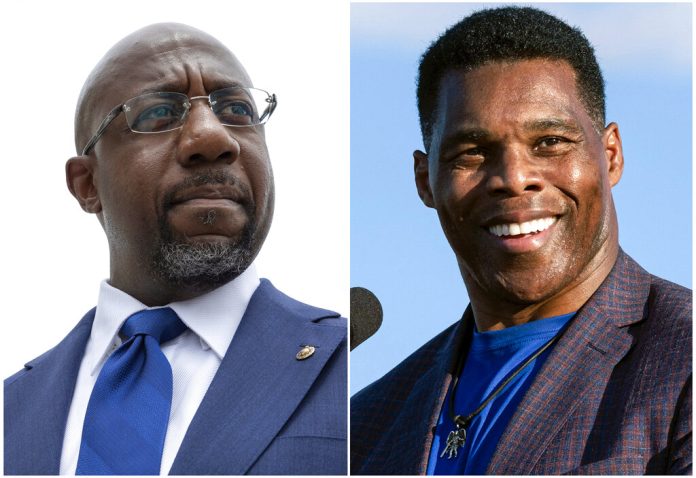

Now he hopes to add another distinction by winning a full six-year term in a Tuesday runoff. Standing in the way is another Black man, Republican challenger Herschel Walker.

Both men have common upbringings in the Deep South in the wake of the civil rights movement and would make history as the first Black person elected from Georgia to a full Senate term. Yet Warnock and Walker have cut different paths and offer clearly opposing visions for the country, including on race and racism.

Black voters say the choice is stark: Warnock, the senior minister of Martin Luther King’s Atlanta church, echoes traditional liberal notions of the Black experience; and Walker, a University of Georgia football icon, speaks the language of white cultural conservatism and mocks Warnock’s interpretations of King, among other matters.

“Republicans seem to have thought they could put up Herschel Walker and confuse Black folks,” said Bryce Berry, president of Georgia’s Young Democrats chapter and a senior at Morehouse College, a historically Black campus where both King and Warnock graduated.

Standing beneath a campus statue of King, Berry continued: “We are not confused.”

Other Black voters raised questions about Walker’s past — his false claims about his business and professional accomplishments, instances of violence against his ex-wife — and the way he stumbles over some public policy discussions as a candidate. Some said they believe GOP leaders are taking advantage of Walker’s fame as a beloved Heisman Trophy winner and national champion running back for the Georgia Bulldogs.

“How can you let yourself be used that way as a Black person?” asked Angela Heard, a state employee from Jonesboro. “I think you should be better in touch with your people instead of being a crony for someone.”

Even some Black conservatives who back Walker lament his candidacy as a missed opportunity to expand Republicans’ reach to a key part of the electorate that remains overwhelmingly Democratic.

“I don’t think Herschel Walker has enough relatable life experience to the average Black American for them to identify with him,” said Avion Abreu, a 34-year-old realtor who lives in Marietta and has supported Walker since the GOP primary campaign.

Warnock led Walker by about 37,000 votes out of almost 4 million cast in the November general election. AP VoteCast, a survey of more than 3,200 voters in the state, showed that Warnock won 90% of Black voters. Walker, meanwhile, won 68% of white voters.

VoteCast data in the 2021 runoff suggested that Black voters helped fuel Warnock’s victory over then-Sen. Kelly Loeffler, comprising almost a third of that electorate, slightly more than the Black share of the 2020 general electorate.

The senator’s campaign has said since then that he’d have to assemble a multiracial coalition, including many moderate white voters, to win reelection in a midterm election year. But they’ve not disputed that a strong Black turnout would be necessary regardless.

The Republican National Committee has answered with its own uptick in Black voter outreach, opening community centers in several heavily Black areas of the state. But the general election results raise questions about the effectiveness, at least for Walker.

Abreu said she believes Walker still can win the runoff but has to do it with the usual, overwhelmingly white GOP coalition moved by party loyalty and the 60-year-old candidate’s emphasis on cultural issues. His campaign, she said, “hasn’t told the full story of Herschel’s life and related that to people, with an explanation of how he is going to help them.”

Indeed, Walker and Warnock share their stories as Black men quite differently.

Warnock doesn’t often use phrases like “the Black church” or “the Black experience,” but infuses those institutions and ideas into his arguments.

The senator sometimes notes that others “like to introduce me and say I’m the first Black senator from Georgia.” He says Georgia voters “did an amazing thing” in 2021 but adds that it’s more about the policy results from a Democratic Senate. Born in 1969, he calls himself a “son of the civil rights movement.” He talks of King’s desire for “a beloved community,” an inclusive society Warnock says is anchored in the belief that “we all carry a spark of the divine.”

He touts his Senate work to combat maternal mortality, noting the issue is acute among Black women. He campaigns with Black fraternity and sorority alumni. And he tells of his octogenarian mother using her “hands that once picked somebody else’s cotton” to “cast a ballot for her youngest son to be a United States senator.”

“Only in America is my story possible,” he concludes.

Walker, alternately, is often more direct in identifying himself by race, usually with humor.

“You may have noticed I’m Black,” he tells audiences that are often nearly all-white. But that jovial aside is the precursor to his indictment of a society — and a political rival — he says are consumed by discussions of race and racism.

“My opponent say America ought to apologize for its whiteness,” Walker says in most campaign speeches, a claim based on some of Warnock’s sermons referencing institutional racism.

Walker invokes King — “a great man” — with a line from his 1963 “I Have a Dream Speech” and accuses Warnock and “trying to divide us” by race. “He’s in a church where a man talked about the content of your character, not the color of your skin,” Walker told supporters in Canton on Nov. 10, his first rally of the runoff campaign. In Forsyth County last week, he blasted schools he insisted teach “Critical Race Theory.”

“Don’t let anyone tell you you’re racist,” he said in August at a “Women for Herschel” event, which included Alveda King, the conservative evangelical niece of the slain civil rights leader.

He blasts Warnock as anti-law enforcement but without any context about police killings of Black citizens. “What I want to do is get behind our men and women in blue,” Walker said in Forsyth.

Walker touts his “minority-owned food services company.” Talking to reporters at one fall campaign stop, he recalled being a freshman at the University of Georgia just a decade after the football program integrated with its first Black scholarship players. But when telling voters of his athletics and professional successes, he doesn’t allude to race, instead talking in terms of faith.

“The Lord blessed me,” he says of each milestone.

It’s a contrast to Warnock’s framing of growing up in public housing in Savannah, choosing Morehouse because of King, and receiving a Pell Grant for tuition assistance. “I’m talking about good public policy,” the senator says.

Doyal Siddell, a 66-year-old Black retiree from Douglasville, said Walker’s pitch is disconnected from many Black voters. “Just because you’re from the community doesn’t mean you understand the community,” he said.

It’s a contrast not entirely explained by partisan identity of philosophy.

Sen. Tim Scott of South Carolina, the Senate’s lone Black Republican, talks openly of his his family’s struggles through Jim Crow segregation, including his grandfather, who never learned to read or write, and he highlights his status as the only Black American in history elected to both the House and Senate.

“Our family went from cotton to Congress in one lifetime,” Scott said as a featured speaker of the 2020 Republican National Convention.

At Morehouse, Berry said Walker could find some Black conservatives and nonpartisans. But he’d have to show up and acknowledge his surroundings.

“You see the senator in the suburbs, in Republican areas,” Berry said. “Herschel Walker has not even been to our campus. He’s not running a campaign that suggests he wants to represent all Georgians.”

___

Associated Press writer Jeff Amy contributed to this report.

___

Follow the AP’s coverage of the 2022 midterm elections at https://apnews.com/hub/2022-midterm-elections.