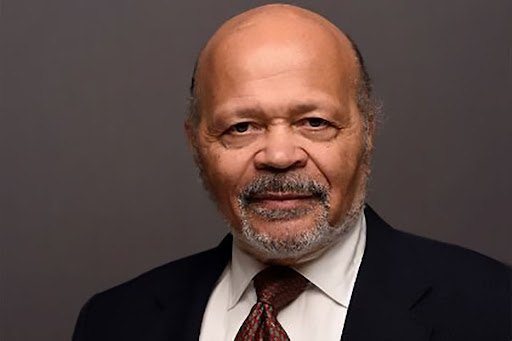

By Oscar H. Blayton

We need not forgive racial injustices in America’s past, and we must never forget them. But as a nation, we can reconcile.

It is undeniable that the flurry of recent activity to suppress this country’s knowledge of its shameful history is an attempt to make us all forget the injustices suffered by large segments of our society. It is also undeniable that forgetting those injustices invites their reoccurrence.

What is imagined to be at stake by those who struggle to bury truths and eviscerate facts is the disappearance of a way of life essential to their very existence. But this only gives testimony to the fact that their cherished way of life is predicated upon injustice.

The danger facing Americans can be demonstrated by looking at South Africa.

South Africa went through a truth and reconciliation process after that nation’s government was forced to end its practice of apartheid in 1994. It was an attempt to put to rest animosity, resentment and fears after centuries of mistreatment suffered by Africans and other people of color at the hands of white supremacist.

History books don’t tell the whole story

Many history books say that apartheid lasted in South Africa only from 1948 to 1994, but that does not tell the whole story. In 1948, the National Party came to power in South Africa and codified the racial segregation in existence there for centuries. Taking a step back in time, history tells us that in 1913, the South African government passed the Land Act soon after it became the Union of South Africa.

One of the provisions of the Land Act decreed that “natives” were not allowed to buy land from whites and vice versa. But more importantly, it was the legal vehicle by which Africans were dispossessed of their lands, much like the First Nations in America had their lands taken from them. This injustice was not solely the doing of South Africans. The Union of South Africa, under Great Britain, came into being when Britain passed the South Africa Act, granting the white minority dominion over Africans, South Asians and other “Coloured” and mixed-race peoples.

At risk of being too tedious with a walk back in time, it needs to be pointed out that South Africa has suffered under white supremacy since the Dutch arrived at the Cape in the 17th century. The Dutch arrived at what became Cape Town, numbering only 90 souls, in 1652. By 1795, they had pushed the Africans off enough land to accommodate 16,000 settlers.

In 2014, almost 400 years after Europeans arrived in South Africa, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) published a report, “The Impacts of Social and Economic Inequality on Economic Development in South Africa.” This dismal recounting of conditions in South Africa makes it clear that four centuries of abuse and injustice fostered by white supremacy have not been healed by 30 years of struggle to set things right. To begin, South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission was created only to investigate gross human rights violations, including abductions, killings and torture, that were perpetrated during the apartheid regime from 1960 to 1994. The period to be examined by the commission was so short that in 2024, as much time will have elapsed since the commission’s creation as the period to be examined itself.

One may ask, “What is the importance of this story to us?”

The answering is frightening. If we consider the painfully short period of time examined by South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the stalled progress to create a better quality of life for those who suffered under apartheid and centuries of abuse, we must realize that forgiving racial injustice can lead to continued inequality. The difference between forgiveness and reconciliation is that forgiveness requires nothing from the forgiven. They may not even have to realize that they are being forgiven. Reconciliation requires repentance from the offender, and the offender does not get to dictate the terms of reconciliation.

Offenders setting the terms of reconciliation

In South Africa, because of the relative strengths of the offenders and the offended, the offenders were able to negotiate – or one might say, “dictate” – the terms of the reconciliation. This should not be allowed to happen in America.

As in South Africa, the United States has for centuries maintained a social regime that allowed atrocious acts of violence and inequality against people with little power to protect themselves. Murder, rape, theft of land, labor and other resources was practiced in plain sight of the global community, with the perpetrators assured that no one would dare interfere to change the status quo.

On Oct. 23, 1947, the NAACP sent to the United Nations a document entitled “An Appeal to the World.” This document asked the U.N. to redress human rights violations being committed in the United States against African Americans.

Many white Americans opposed the petition, including then-former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who was a member of board of directors of the NAACP and a member of the American delegation to the United Nations. The Soviet Union, however, proposed that the NAACP’s charges be investigated. But on Dec. 4, 1947, the U.N. Commission on Human Rights rejected that proposal, and the United Nations took no action on the petition.

As we continue our struggle for justice, we must keep in mind that while we should not forgive, and forget our shared history with those who have benefited from the many injustices we have suffered, we should be prepared to seek to find a way towards a true reconciliation.

Oscar H. Blayton is a former Marine Corps combat pilot and human rights activist who practices law in Virginia.