By Jill Castellano, inewsource.org

The high death rate in San Diego County’s jail system has troubled attorneys, lawmakers and community activists for years. It has prompted audits, lawsuits and a new state law to enact jail reforms.

The same crisis is unfolding in another nearby jail system. In Riverside County, the jail death rate rose significantly in 2022, surpassing that of San Diego and most large California counties, according to an inewsource analysis.

Nineteen people died in Riverside County jails in 2022. They were primarily young Hispanic men awaiting trial. They ranged in age from 20 to 78 years old. They died from overdoses, suicides and other causes. Like in San Diego, their families want answers and accountability.

Pressure is building in Riverside. The California Attorney General’s Office opened an investigation into the jail system in February, and at least five lawsuits were filed in May by families of the deceased.

inewsource spoke with advocates and decision makers who have been directly involved in pushing for reforms in San Diego’s jails. They reflected on their successes, their failures and what people in Riverside County can learn from their efforts.

“It isn’t just a San Diego problem,” said California State Senate President pro Tempore Toni Atkins, a Democrat who represents San Diego in the Legislature.

“You’ve got numbers from LA County, Riverside — you’ve got a number of counties that are under consent decree,” said Atkins, referencing court-mandated reforms in the jails.

“This means that it is a culture issue and something that needs to be addressed statewide.”

Atkins’ jail reform bill, SB 519, grew out of conversations with activists and officials in San Diego County over the past few years as the death toll in detention centers climbed. It was signed into law by the governor on Oct. 4.

The new law gives the public access to reports of in-custody deaths — records the San Diego County Sheriff’s Department has fought against disclosing in an ongoing court case. It also establishes a new governor-appointed official to review death investigations with the help of medical and mental health professionals.

While Atkins called the law “a step forward, absolutely,” she also acknowledged her work isn’t done.

Earlier versions of the bill called for more oversight power of county jails, but the text went through rounds of revisions that removed some of its teeth. In an early draft, the in-custody death reviewer could have taken over jail operations from a problematic sheriff’s department. Now, that reviewer can only make recommendations.

“I had to negotiate, and I had to compromise,” Atkins said.

The path toward jail reform in San Diego has frustrated activists who have faced numerous obstacles.

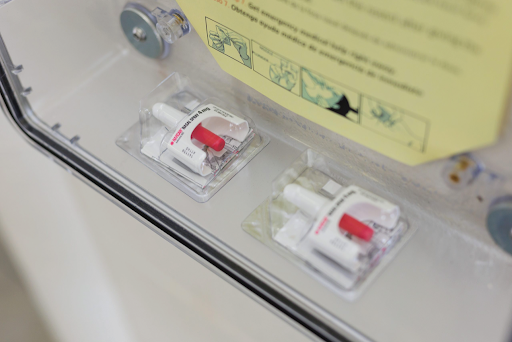

Gretchen Burns Bergman, the founder of the addiction recovery program A New PATH, said the sheriff’s department hasn’t always been cooperative with her team. When her nonprofit donated hundreds of kits of naloxone — an overdose reversal drug — to the jails during the COVID-19 pandemic, correctional officers did not use them because of resistance from union leadership. The kits eventually expired.

“To think about the months and how many people lost their lives because this wasn’t implemented when they said it would,” Burns Bergman said. “It was heartbreaking.”

San Diego County Sheriff Kelly Martinez made a commitment to improving jail conditions when she began her term last January. But advocates pointed to several ongoing points of tension.

Despite promising to make in-custody death reports public, the sheriff’s department has only posted summaries online. And while drug screening has ramped up for incarcerated people when they enter the jails, Martinez has resisted calls to screen the correctional officers.

Burns Bergman acknowledged that well-intentioned reforms can get weighed down in bureaucracy. She encouraged community members in Riverside and elsewhere to keep reminding county leaders of the changes they wish to see.

“It’s all about the people on the ground,” Burns Bergman said. “Like we are just constantly bugging the criminal justice system for these reforms.”

In an email, San Diego County Sheriff’s Department spokesperson David Ladieu said the office is working collaboratively with other jail systems facing the same challenges, namely, “aging facilities, industry wide staffing challenges, and a population that is diverse and requires high levels of care.”

In November, Martinez announced a nearly $500 million plan to modernize the county’s aging jails over the next decade. Officials are expected to report back to county supervisors in June on how they plan to fund the improvements.

“Providing a safe and secure facility for incarcerated individuals and our staff is a priority for Sheriff Martinez,” Ladieu said. “She is earnest in having a coordinated approach to medical and mental healthcare, as well as reentry programs in our jails to address the underlying issues of rehabilitation and reintegration.”

Paul Parker, executive officer of the county’s Citizens Law Enforcement Review Board (CLERB), said the sheriff’s department is committed to improving jail conditions.

CLERB’s mandate includes reviewing in-custody deaths. Not long after the sheriff began her term in December 2022, Parker said he was given permission to visit the scene of every death that occurs in county jails and incorporate that information into his reports.

Still, CLERB only serves an advisory role to San Diego’s elected sheriff, who has a lot of autonomy.

Oversight in Riverside County is even less robust. There is no independent review board, and the county supervisors have little authority over the department beyond approving its annual budget.