By Helen Kapstein, John Jay College of Criminal Justice

“Beloved.” “The Hate U Give.” “Maus.” “Burger’s Daughter.”

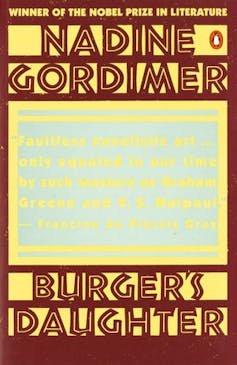

Each of these books has been banned at some point in time, but one stands out. Instead of being banned in 21st-century America, Nadine Gordimer’s “Burger’s Daughter” was banned in 20th century South Africa during apartheid, that country’s period of official white supremacist rule.

So why include it in this list? Despite the decades and distance between bans on this book and the others, the rise in attempts to ban and censor books in America in 2022 looks an awful lot like what South African censors did during apartheid. I make this observation as a scholar who specializes in studying literature to better understand the intersections of race, oppression and resistance.

When apartheid censors – who operated under the Directorate of Publications – sought to crack down on what they found offensive, they used terms like “sedition,” “blasphemy” and “obscenity” to justify their acts. In the 2020s in the U.S., people who’d like to censor books use labels like “objectionable,” “pornographic” or “dangerous.” Then as now, the criteria used to censor books are so broad and subjective that almost any book could be challenged on practically any grounds.

To my eye, it’s almost as though would-be American censors have taken a page directly from the South African censors’ playbook. And it’s not just that they look similar in their rationale. Rather, in my view, it’s that they set out to squash political dissent and silence social debate. Here are the similarities I see:

1. Manufactured outrage

Outrage about the content of books is often disingenuous, misplaced or manufactured.

In 1972, South African author Alex La Guma, who was officially categorized as “coloured” under the country’s racist regime, had already been forced into exile. As a person banned by the South African government, his writing already couldn’t legally be distributed inside the country. Yet, his novel “In the Fog of the Seasons’ End” was still banned for threatening state security and good order. This bureaucratic overkill speaks to the urge to censor even when it’s absurd – the authorities were banning a book that by their own rules no one could read.

La Guma’s book depicted the death and torture in detention of an anti-apartheid resistance fighter, causing the censors to complain about the book’s “wild writing against the police.” But another of his novels, “The Stone Country,” was banned even though the censors themselves acknowledged that there was nothing in the plot that merited it. This shows their willingness to manufacture a threat where none exists.

In the United States in 2022, there are reports of parents shouting at school board meetings or storming town halls, upset about material their children are exposed to and demanding it be removed from school library shelves and classrooms. Are these headline-grabbing moments spontaneous, grassroots and earnest efforts to protect innocent young minds? Or are they highly orchestrated, heavily funded and deliberately manufactured schemes to advance an ultra-conservative agenda at the expense of free speech and expression? It can be hard to tell.

While we cannot know anyone’s intent for certain, we do know that when people act to limit a society’s access to literature and libraries, and therefore to other worlds and possibilities, it makes it easier to limit its political imagination.

2. White discomfort

South African censors objected that “Burger’s Daughter” brought Afrikaners – that is, South Africans of Dutch descent – into “ridicule and contempt,” fundamentally misunderstanding how the whites in the novel are depicted. The censors’ unimaginative defensiveness is much like the language of white “discomfort” we hear bandied about in current politics.

At the same time as South Dakota tried to pass a bill that forbade discussion of any history that causes white discomfort, Florida, in spring 2022, passed the “Individual Freedom” law, which states that “an individual should not be made to feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress on account of his or her race.” State Senator Shevrin Jones said, regarding the bill, “This was directed to make whites not feel bad about what happened years ago.”

3. Euphemism

The South African Publications Act may sound supportive of publishing but in fact was intended to censor and control it.

Likewise, the various acts and bills being passed in America today often slide through legislatures with deceptively bland names. For instance, Florida’s “K-12 Education” law requires all school materials be posted and searchable.

Proponents of the law said it was meant to help parents make decisions regarding their children’s education. But in reality, as pointed out by the National Coalition Against Censorship, the mechanism could discourage teachers and librarians from taking risks with teaching material that might lead to complaints from parents.

New legislation also sneaks through in euphemistic disguise, such as the wave of so-called “transparency bills” which use the language of transparency to embolden public scrutiny. Moreover, the bills themselves are not at all transparent.

One bill prohibits the discussion of “any controversial subject matter”, and another mixed up two historical figures. Vague wording, undefined terms, contradictory language and factual errors all make them more “sweeping” and “draconian,” as PEN America describes them.

4. Proxy wars

Hand-wringing over what’s “age-appropriate” is often a proxy today for suppressing other, potentially controversial conversations about subjects like sexuality.

In South Africa under apartheid, such a conversation was the mixing of races. “Burger’s Daughter,” for instance, was called “indecent” partly because a Black child and a white child play together in it.

Here in the U.S., books are also called “objectionable” by lawmakers and parents for reasons other than the real ones. Toni Morrison’s “Beloved,” for example, gets an “NSC … not suitable material or conduct for minors per existing statute” rating for sections mentioning the “n word,” among other objections, from the Florida Citizen’s Alliance 2021 Porn in Schools report.

Ironically, the report labels itself as “contain[ing] objectionable and potentially offensive material.”

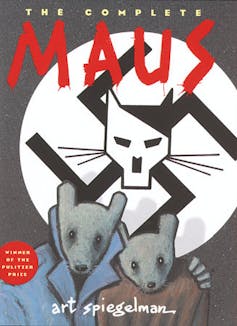

In January, a school board in Tennessee removed “Maus” from the curriculum in the name of “inappropriate words” and “objectionable language,” including profanity. However, some people, including the graphic novel’s author, Art Spiegelman, believe the real reason it was removed was disinterest in or discomfort with Holocaust education on the part of Tennessee lawmakers.

5. Unbanning and other doublespeak

“Burger’s Daughter” was first banned under the 1974 Publications Act and then unbanned. Gordimer, however, saw the lifting of the ban as a charade to make the apartheid regime look more fairminded.

A Virginia court ruling also exposes the murky area between banning and unbanning. In May 2022, a Virginia Beach judge declared two books “obscene for unrestricted viewing by minors.” Even though schools and bookstores might now be prohibited from distributing the books to young readers without parental consent, the attorney who won the case insists that, “It doesn’t mean the books are banned. It doesn’t mean we’re burning books or infringing on free speech.”

These rulings, in my view, are largely political theater. If proponents of censorship in the U.S. today are thumbing through the South African playbook, they might learn that it’s savvy to sound tolerant, if only for show.

After all, South African censors were devious enough to figure that banned books were of more use to the anti-apartheid movement because they they’d get notoriety. If the book were no longer banned, then they’d lose much of their appeal. They knew the threat of banning can actually backfire and generate more interest in the books.

Our modern American censors may be cribbing from South Africa’s notes, but they should read to the end of the history book. Despite its repressive tactics, that white minority government could not stay in power, and it was apartheid itself that wound up banned. There’s a lesson for the books.![]()

______