LOS ANGELES (AP) — Filmmaker Allen Hughes thought participating in any Tupac Shakur project was a farfetched idea especially after surviving a brutal altercation involving him and the rap legend three decades ago.

For years, Hughes firmly held a grudge even after a public apology from Shakur — who along with nearly a dozen gang members in 1993 physically attacked the filmmaker for firing the rapper from the cult classic “Menace II Society.” He along with his brother Albert Hughes had previously directed Shakur’s “Brenda’s Got a Baby” music video in 1990s. After the dispute, Shakur was convicted and served about two weeks in jail.

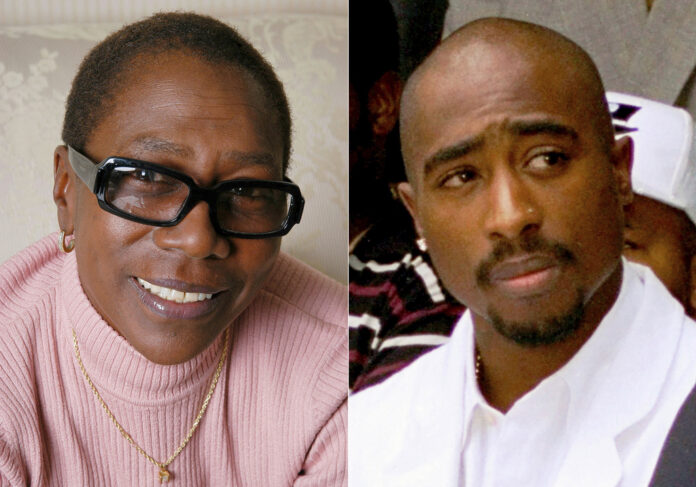

It took Hughes some time, but he finally stopped holding onto his deep-seated resentment a few years ago when Shakur’s estate approached him to direct a documentary called “Dear Mama,” which premieres Friday on FX and will stream the following the day on Hulu. The five-part docuseries explores how the mother-son duo of Tupac and Afeni Shakur shaped American history.

With never-before-seen footage, “Dear Mama” delves into Afeni’s past as a female leader in the Black Panther Party, while exploring Tupac’s journey as a political visionary and becoming one of the greatest rap artists of all time.

In an interview with The Associated Press, Hughes talks about the reason he took part in “Dear Mama” despite the previous beef, revelations the project gave him about the rapper and how the outspoken Tupac would fit into today’s world.

Remarks have been edited for clarity and brevity.

___

AP: Given your turbulent past with Tupac, did you have any hesitation about doing this project?

HUGHES: I wasn’t sure if I wanted to do it because of obvious personal reasons. It takes a lot out of you doing documentaries too — especially if you do it over the course of a few years, like we did this one. But once I realized that there wasn’t enough about Tupac that I didn’t realize, it might be better to explore him through his mother and make it a dual narrative. The estate and family were down with that.

AP: How did you get over that altercation?

HUGHES: It took a few years for me to get over it. First of all, I saw the apology in real time. I wish I was man enough to have connected with him at the time. I’ve since seen all the audio visuals with him saying he was remorseful about it, which I never knew existed. But we were kids. We were all 19 when that happened. No, you should never take it to the level of violence, whatever the misunderstanding is. But I’ve been in fist fights with my brother and recovered. Tupac loved hard. When he got angry, it was hard. I think maybe with the trauma from being completely obliterated by 10-15 guys, it just took a lot.

AP: What was your clinching factor to do this project?

HUGHES: I was standing on Malibu Beach and I’m walking. That’s when it happened.

In the meeting, when I went back to accept the assignment, one of the people from the estate slid an address in a piece of paper over to me. I’m like, “What is this?” And they go, “Your address is yards away from where we put Tupac’s ashes.” That’s when I got goosebumps. That’s when I definitely knew I made the right decision.

AP: What new did you learn about Afeni while filming the project?

HUGHES: I knew she was a Black Panther. I knew she had an addiction difficulties and challenges that she overcame. That’s all I knew. Anything in the film about her in the Panther 21 case trial that they were going to be sent way for 360 years for allegedly plotting to bomb all these places in and around New York City and her defending herself. Her closing statement to the court. I didn’t know any of that stuff. And why she struggled with addiction post with that whole thing happening with the Panthers and then being dismantled by the FBI.

AP: What about Tupac?

HUGHES: I didn’t know about his poverty. I come from welfare in the worst parts of Detroit being just poor. But my poorness pales in comparison to Tupac’s poverty and not knowing where your next meal is going to come from throughout your adolescence. I didn’t know there was an expectation for him to pick the Black Panther movement up and become the new leader.

AP: Was the title “Dear Mama” an easy choice?

HUGHES: People were very reluctant. It wasn’t called “Dear Mama.” It was called “Outlaw” for a long time. Then I was like, “Wait a minute, duh.” I had to get approval from the estate. It took a while. You know, it wasn’t easy.

AP: In the docuseries, how did societal issues impact both Afeni and Tupac?

HUGHES: As he said in that 17-year-old high school interview, Tupac really moved me when he says “We’re poor because our ideals always got in the way.” Principles don’t pay. There’s not big bucks in morals. But to see that woman so ahead of her time. Her main focus was equipping this young Black boy to protect himself here first with his mind, with the knowledge of self. When you hear in the first episode why she named him Tupac, it’s because she wanted to make sure he knew Black people weren’t the only people that were made to suffer like this in the world. This is a global. This is a human condition. He was named after a famous South American martyr. That tells you how worldwide she was and curious. I think that’s inspiring to anyone from our generation: white, Black and Asian, whatever.

AP: If Tupac was still alive, what mark would he make in society today?

HUGHES: His friend said in the movie towards the end, ‘He couldn’t live in this world today.’ He couldn’t accept what you and I accept. He would be an (expletive). If the thing was like, “Hey, let’s go catch butterflies.” He would mobilize a million people with butterfly nets. He can move the crowd. If he was here, I doubt that we would have had to have a Black Lives Matter movement because that’s how strong he was in his spirit. He was meant to be a civil rights leader. He was meant to be an activist. That’s what was expected of him. And then this little thing called hip-hop derailed that plan. He had that very thing the FBI was trying to bring down. The next Black Messiah. He had that quality. It would be a lot different.