Descendants of African slaves along the southeast U.S. coast battle climate change, gentrification and cultural assimilation.

By Kevin Michael Briscoe

ST. AUGUSTINE, Fla. — Among the more than 100 Sea Islands that stretch from Georgetown County, S.C., to Amelia Island, Fla., and about 30 miles inland, is the home of the Gullah Geechee people.

As climate change continues to ravage these coastal areas — and gentrification infringes upon their ancestral birthplace — these descendants of African slaves are fighting to maintain the traditions and cultural heritage that are in danger of being forgotten.

At the forefront of this fight are two St. Helena Island, S.C.-born women, and another from north Florida, who are each working locally and internationally to avoid the “museumization” of their Gullah ancestry.

Isolation builds a creole culture

“The Gullah people came about after our ancestors were stolen from the rice-growing regions of Central and West Africa. They were highly sought after because the colonists wanted to grow rice here in a specific area now known as the Gullah Geechee Corridor,” said Victoria Smalls, a U.S. National Park Service ranger and historian for the Reconstruction Era National Historical Park in Beaufort, S.C. “So, they went to the Windward Coast to get the ‘experts,’ the people who knew how to grow, cultivate and harvest rice, and knew the engineering behind hydrology.”

The experiences of these slaves, typically transported from places such as Angola, Sierra Leone, Madagascar and Mozambique, were different from those of their counterparts in other parts of the colonies. While those slaves had more interaction with whites and British-American culture, the Sea Island and Lowcountry slaves of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida were largely left isolated as their slave masters fled the rice fields for months at a time out of fear of malaria and yellow fever.

“The nature of their enslavement really isolated them on these Sea Islands and coastal areas,” said Smalls. “Some of these islands, to this day, still don’t have bridges to connect them to the mainland, resulting in little interaction with their enslavers or people outside of the community. So, they were able to retain a lot. That isolation served as an incubator to protect their cultural ways.”

This isolation created a creole culture — an amalgam of Baga, Fula, Kpelle, Limba, Mandinka, Mende, Susu and other ethnic groups — that established a common language, now known as Geechee. Today, Gullah and Geechee are used interchangeably to describe both the people and their language.

“They melded English with more than 4,000 West African words to make up the Gullah language,” said Smalls, who counts Gullah as her first language. “They also incorporated Central and West African foodways, spirituality and religion, music and crafts into their life in the New World.”

One of 14 siblings, Smalls grew up in the first biracial family on St. Helena Island. Her father, a widowed black man with six black kids, and her mother, a widowed white woman with four white kids from Petoskey, Mich., met at the island’s famed Penn School, and together had four more children, including Smalls.

“Ghana, Nigeria, Benin, Guinea-Bissau, Sierra Leone, Mali — all of them are my ancestral countries,” she said. “I also have Cherokee blood and, of course, my European background. I’m actually more European than African — 52 percent. I love my mother, but the person I am today is unapologetic about who I feel that I am in my African ancestry.”

Promote globally, preserve locally

Smalls is also a former commissioner of the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor, a 15-member non-profit organization based on Johns Island, S.C., that says it’s mission is to “preserve, share and interpret the history, traditional cultural practices, heritage sites and natural resources associated with Gullah Geechee people of coastal North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia and Florida.”

The commission, which manages the corridor through the Park Service’s National Heritage Areas program, provides educational programs for public, technical assistance to academics and historians, and partnerships with public and private entities to protect the Gullah Geechee culture.

“The Corridor commission is largely people who are academics; they’re not necessarily native Gullah Geechee people,” said Marquetta L. Goodwine, also known as Queen Quet, chieftess of the Gullah Geechee Nation. “So, if you want to hear the people’s voice, you go to the people. The [Gullah Geechee] people elected me, and we have a Wisdom Circle Council of Elders and an Assembly of Representatives that are native Gullah Geechee that the Gullah Geechee people put in place.”

Goodwine founded the Gullah/Geechee Sea Island Coalition in 1996 to advocate for the preservation of Gullah Geechee cultural traditions. On April 1, 1999, she became the first Gullah to speak before the United Nations’ Committee on Human Rights in Switzerland on the struggles of her people. Based on her lifelong commitment to the culture, including a stint as a commissioner on the inaugural Corridor commission, Goodwine said she was elected to her position after a year-long petition drive among the nation that was supervised by U.S. and U.N. election observers.

To Westerners, she said the process of her ascension is confusing because it does not resemble the elements of a typical political campaign.

“In my case, we used an African traditional methodology,” said Goodwine. “Elders from across the Carolinas, Georgia and Florida had been watching the work that I’d been doing for four decades. Folks were really starting to pay attention because of the continuous onslaught of disturbances to our land and the displacement of our people. The petition was taken to various events, community centers, and also put online. On July 2, 2000, the confirmation of the results took place on Sullivan’s Island, S.C.”

Goodwine likened the Wisdom Circle Council to a presidential cabinet, and described the Assembly of Representatives as “Congress, just better behaved.”

“We are not necessarily intended to be a mimicry of Western structure and hierarchy,” said Glenda Simmons Jenkins, an Assembly of Representatives member based on Amelia Island in north Florida. “It’s more of a communal understanding of how we interact with each other. Naturally, we’re influenced by the actions of governments around us, so when local governments do things and have policies that impact our sustainability or survival, we have to respond to it.”

“We have our own constitution, our own set of laws that governs us, but we are also dual citizens of the United States,” Goodwine said. “By declaring internal human rights, we were able to stand on self-determination, and maintain our status as U.S. citizens and our own nation citizenship as well.”

Climate change and gated communities are a real threat

Within weeks of his 1864 scorched earth “March to the Sea” from Atlanta to Savannah that broke the spirit of the Confederate Army, Union Army Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman issued Field Order No. 15, which divided 400,000 acres into 40-acre allotments for use by the “settlement of the negroes now made free by acts of war and the proclamation of the President of the United States.” The order also made it illegal for whites to set foot on this property along the Sea Islands. The latter is especially significant, as the Ku Klux Klan has never invaded the property set aside for freed slaves, thus further insulating them from much of the racism that gripped the American South.

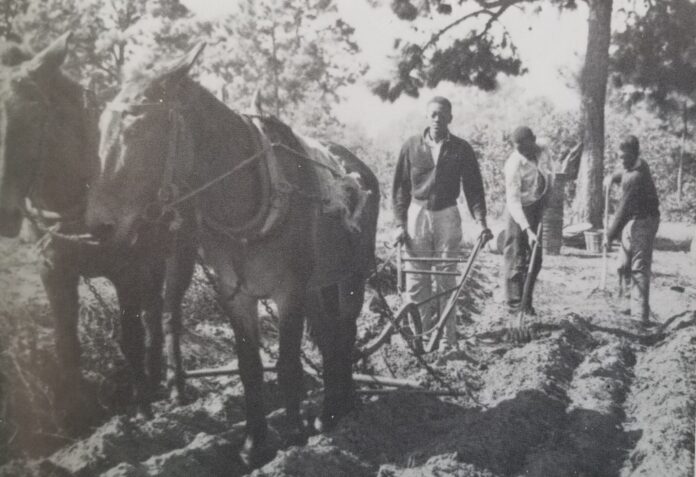

Although President Andrew Johnson later rescinded the order, the Gullah people of the period purchased much of the land at auctions, creating a self-sufficient agrarian and fishing-based local economy. Smalls’ second-great-grandparents, Adam and Betsy Smalls, in fact, purchased 59 acres of land to establish a Sea Island cotton farm on St. Helena Island in the 1860s.

“But if you didn’t have a good crop, or there was a flood or hurricane, or the boll weevil devastated your crop, you couldn’t pay the taxes on that land,” Victoria Smalls said. “So, Adam and Betsy had all 59 acres taken away by the [local] cotton gin. They got it all back, then lost it again, then got it all back.”

Today, Smalls and eight other siblings own about 20 acres of what she called her “heirs’ property,” providing food to local elders and selling their wares at area co-ops.

“I want to build a house on St. Helena for my children,” said Smalls, who lives in nearby Beaufort. “But, I’m worried about sea level rise and climate change and, in 50 to 75 years, will that land still be there?”

Also having a negative impact on the Sea Islands is a proliferation of wealthy gated communities and beach resorts from Jacksonville, N.C., to Jacksonville. Fla.

“A lot of my time these days is with climate actors, people who are activists in the arena of climate change dynamics, and trying to ensure that cultural heritage is a part of the resiliency and sustainability plans that many local governments are working on,” Goodwine said.

The evolution of the Gullah Geechee Corridor is the “continuation of a holocaust” that has its origins in the immediate post-Civil War era, according to Goodwine.

“It lends itself to the cultural harm that happens when people build resorts and gated communities right into the culture, which drives up taxes and pushes people off their land because they can’t economically afford to hold onto it. A lot of Gullah Geechee people are land rich and cash poor,” she said.

In addition, toxic run-off from golf courses and resort properties leads to ocean acidification, which disrupts the delicate ecosystem that Gullah fishermen rely on: healthy bacteria to break down dead plant life, which feeds the algae that attracts snails, clams, oysters and crabs.

“What’s being built on these coasts is causing massive negative impacts on the environment, and that lends itself back to the economic impact because counties have to increase taxes on the natives, when we have nothing to do [with creating the problem in the first place]. They are more accommodating to the ‘come-heres’ than the ‘been-heres,’” said Goodwine.

Enlightening the next generation

In addition to battling the effects of gentrification and climate change, the Gullah Geechee community is grappling to stay relevant, balancing the continuation of rich traditions and values with ongoing cultural assimilation.

“God has a way. What we’re seeing is that there are a lot of young people who would’ve never paid attention to Gullah Geechee lifestyle and customs had it not been for the pandemic,” said Jenkins. “They are forced to pay attention to what we are doing to maintain our culture and systems, and our focus on the agrarian lifestyle. My 22-year-old daughter has been observing Gullah Geechee traditions … since she was 4 years old. But, now it’s up close and personal. When she came home from college, she said, ‘Mom, we need to plant a garden.’ If we lose indigenous cultures, like the Gullah Geechee, we lose the knowledge that the earth is not something you fight, it’s something you fight for.”

“I would argue that, with any culture that’s been here in America, every generation becomes more Americanized, and you might lose a bit of your culture,” said Smalls. “It’s no different for the Gullah Geechee people; if our ancestors don’t continue to pass things down, some things could be forgotten.

“But we have it so deep in our DNA, it’s going to come out in some way.”

(Edited by Stan Chrapowicki and Matthew B. Hall)