By AMY FORLITI, STEVE KARNOWSKI and TAMMY WEBBER, Associated Press

A jury that appears to be all-white began deliberating Wednesday at the federal trial of three fired Minneapolis police officers charged with violating George Floyd’s civil rights when he was pinned to the ground for 9 1/2 minutes as fellow Officer Derek Chauvin pressed his knee into his neck.

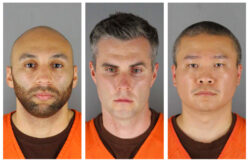

J. Alexander Kueng, Thomas Lane and Tou Thao are charged with depriving Floyd of his right to medical care. Kueng and Thao are also charged with failing to intervene to stop Chauvin during the May 25, 2020, killing that was captured on bystander video that triggered protests worldwide and a reexamination of racism and policing.

Prosecutors told jurors during closing arguments that the three officers “chose to do nothing” as Chauvin squeezed the life out of the 46-year-old Black man. Defense attorneys countered that the officers were too inexperienced, weren’t trained properly and did not willfully violate Floyd’s rights.

All 12 members of the jury — eight women and four men — appear to be white, although the court has not released demographics such as race or age. A woman who appeared to be of Asian descent was excused Tuesday from the panel without explanation; a man who appears to be of Asian descent remains as an alternate if one of the current 12 cannot continue.

Lane is white, Kueng is Black and Thao is Hmong American.

That is a sharp contrast to the jury that deliberated the state murder case against Chauvin. That jury was half white and half nonwhite, according to demographic information provided by the Hennepin County court.

The federal jury pool was selected from throughout the state, which includes areas much more conservative and less diverse than the Minneapolis area from which the jury for Chauvin’s trial was drawn. Chauvin was convicted of murder and manslaughter, and later pleaded guilty to a federal civil rights charge.

In this case, four jurors are from Hennepin and Ramsey counties, where Minneapolis and St. Paul are located, and three are from mostly suburban counties. Five are from counties in southern Minnesota, including a woman from Jackson County, along the Iowa border.

They have diverse educational backgrounds and life experiences, including a project captain at an architectural firm, a man with a degree in French and education, a computer programmer, a retired hospital chef and a woman who home-schools her children.

Alan Tuerkheimer, a Chicago-based jury consultant, said potential jurors with obvious extreme views about the case likely were weeded out during jury selection. But the geographic makeup of the final 12 could matter.

“The more suburban, the more rural, the less-populated place, the more deferential attitude there is to police,” said Tuerkheimer, who lived in Minnesota for several years. “I think that’s something the defendants had going in: When you broaden the pool outside the metro area, you do tend to get people who are a little more sympathetic (to police).”

Prosecutors sought to show during the monthlong trial that the officers violated their training, including when they failed to roll Floyd onto his side or give him CPR. They argued that Floyd’s condition was so serious that even bystanders without basic medical training could see he needed help.

But the defense said the Minneapolis Police Department’s training was inadequate and that the officers deferred to Chauvin as the senior officer at the scene.

Chauvin and Thao went to the scene to help rookies Kueng and Lane after they responded to a call that Floyd used a counterfeit $20 bill at a corner store. Floyd struggled with officers as they tried to put him in a police SUV.

Thao watched bystanders and traffic as the other officers held down Floyd. Kueng knelt on Floyd’s back and Lane held his legs. All three officers, who are out on bail, testified in their own defense.

Thao’s attorney said his client thought the officers were doing what they believed was best for Floyd — holding him until paramedics arrived. Kueng’s attorney said police weren’t adequately trained on the duty to intervene. And Lane’s attorney said his client suggested rolling Floyd onto his side so he could breathe, but was rebuffed twice by Chauvin.

U.S. District Judge Paul Magnuson went through the counts Wednesday, telling jurors what they must consider. For example, he defined reasonable force and said if the jury finds that Chauvin used unreasonable force — and that Thao and Kueng had a realistic opportunity to intervene to stop it — then they must find that they deprived Floyd of his right to be free from unreasonable force under the Constitution.

He also reminded jurors that they need to consider the evidence against each man separately and return a separate verdict for each count.

The jurors are not sequestered — isolated from outside influences that could sway their opinion — which is sometimes done by having them stay in hotels during deliberations.

About an hour after the jurors got the case, attorneys wheeled a cart with exhibits out of the courtroom. The jurors are allowed to watch videos from the scene and view other evidence as much as they want during their deliberations.

Federal civil rights violations that result in death are punishable by up to life in prison or even death, but those sentences are extremely rare, and federal sentencing guidelines suggest the officers would get much less if convicted.

Lane, Kueng and Thao also face a separate trial in June on state charges alleging that they aided and abetted murder and manslaughter.

___________________________________________

Webber reported from Fenton, Michigan. Associated Press writer Doug Glass contributed from Minneapolis.

___________________________________________

Find AP’s full coverage of the killing of George Floyd at: https://apnews.com/hub/death-of-george-floyd