Courtesy of Drum Beats La

On Dec. 26, millions throughout the world’s African community will start weeklong celebrations of Kwanzaa. There will be daily ceremonies with food, decorations, and other cultural objects, such as the kinara, which holds seven candles. At many Kwanzaa ceremonies, there is also African drumming and dancing.

It is a time for communal self-affirmation—where famous Black heroes and heroines, as well as late family members—are celebrated.

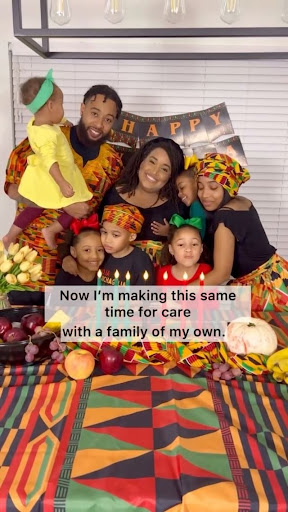

The Saunders family of Baton Rouge continues a tradition of celebrating Kwanzaa and helping others understand the importance of this holiday.

History of Kwanzaa

Maulana Karenga, a noted Black American scholar, and activist created Kwanzaa in 1966. Its name is derived from the phrase “matunda ya kwanza” which means “first fruits” in Swahili, the most widely spoken African language. However, Kwanzaa, the holiday, did not exist in Africa.

Each day of Kwanzaa is devoted to celebrating the seven basic values of African culture or the “Nguzo Saba” which in Swahili means “seven principles”. Translated, these are: unity, self-determination, collective work and responsibility, cooperative economics (building Black businesses), purpose, creativity and faith. A candle is lit on each day to celebrate each one of these principles. On the last day, a black candle is lit and gifts are shared.

Today, Kwanzaa is quite popular. It is celebrated widely on college campuses, the U.S. Postal Service issues Kwanzaa stamps, there is at least one municipal park named for it, and there are special Kwanzaa greeting cards.

Kwanzaa is not just any “Black holiday.” It is the recognition that knowledge of Black history is worthwhile.

For the first time, a large Kwanzaa kinara stands in downtown Detroit’s Campus Martius Park, joining the 65-foot Christmas tree and the 26-foot-tall Hanukkah Menorah that have marked the holiday season in the Motor City for years. Erected this week, the 30-foot tall kinara monument is believed to be the largest in the world, and it now stands in one of the largest Black-majority cities in the U.S.

Kwanzaa’s meaning for Black community

Kwanzaa was created by Karenga out of the turbulent times of the 1960s in Los Angeles, following the 1965 Watts riots, when a young African-American man was pulled over on suspicion of drunk driving and beaten by six police officers, resulting in an outbreak of violence.

Subsequently, Karenga founded an organization called Us – meaning, Black people – which promoted Black culture. The organization’s purpose was to provide a platform that would help rebuild the Watts neighborhood through a strong organization rooted in African culture.

Karenga called its creation an act of cultural discovery, which simply meant that he wished to point Black Americans to greater knowledge of their African heritage and past.

Rooted in the struggles and the gains of the civil rights and Black power movements of the 1950s and 1960s, it was a way of defining a uniquely Black American identity. As Keith A. Mayes, a scholar of African-American history, notes in his book,

“For Black power activists, Kwanzaa was just as important as the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Kwanzaa was their answer to what they understood as the ubiquity of white cultural practices that oppressed them as thoroughly as had Jim Crow laws.”

Today, the holiday has come to occupy a central role, not only in the U.S. but also in the global African diaspora.

A 2008 documentary, “The Black Candle” that filmed Kwanzaa observances in the United States and Europe, shows children not only in the United States but as far away as France, reciting the principles of the Nguzo Saba.

It brings together the Black community, not on the basis of their religious faith, but a shared cultural heritage. Explaining the importance of the holiday for African-Americans today, writer Amiri Baraka, says during an interview in the documentary,

“We looked at Kwanzaa as part of the struggle to overturn white definitions for our lives.”

Indeed, since the early years of the holiday, until today, Kwanzaa has provided many Black families with tools for instructing their children about their African heritage.

Kwanzaa is centered around seven principles and each day of the seven day observation is dedicated to one of “The Seven Principles of Kwanzaa.”

There are seven symbols of Kwanzaa: mazao (crops), mkeka (mat), kinara (candleholder), muhindi (corn), kikombe cha umoja (unity cup), zawadi (gifts), and mishumaa saba (seven candles) which are arranged on a table. Three of the seven candles are red, representing the struggle; three are green, representing the land and hope for the future; and one is Black, representing people of African descent.

Kwanzaa celebrants commit to incorporating seven principles into their daily lives:

- Umoja: To maintain unity in the family and community.

- Kujichagulia: Self-determination – to be responsible and speak for oneself.

- Ujima: Collective work and responsibility – to build and maintain a community.

- Ujamaa: Economic cooperation – to help and profit one another.

- Nia: Purpose – to build and develop the community for the benefit of the people.

- Kuumba: Creativity, to do everything possible to leave the community more beautiful and beneficial for future generations.

- Imani: Faith – to believe in parents, teachers, and leaders.

Families host a communal feast called a Karamu, exchange homemade gifts, and recommit to these principles from December 26 through January 1.

“Each of us who understand what’s happening to our collective communities can and must do something. The seven principles of Kwanzaa, if applied year-round, can change the negative paradigm in which we find ourselves. It appears that Black people must band together and help each other survive the tyranny of those who endeavor to oppress us….still,” writes The Louisiana Weekly.