by Foluké Tuakli

No one called Laolu Senbanjo black until he was in his 30s.

A native of Nigeria, which Senbanjo noted has more than 300 tribes, the artist identifies as Yoruba, one of the country’s largest ethnic groups. But when Senbanjo first immigrated to New York in 2013, becoming black was part of his welcome.

“New York for me when I was growing up on TV was like,’ Oh wow, I should just go to New York,'” he said. “And you get here and you have a rude shock of like, ‘Wow, it’s crazy’ … And I just, nobody has ever called me black before. That was something that was immediate, you know? I felt it.”

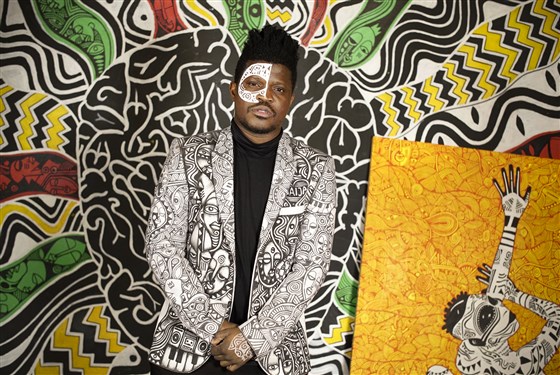

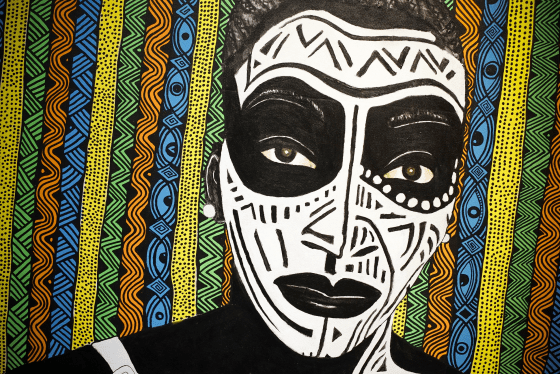

Senbanjo’s work features strong figures, lines, and symbols illustrated on everything from shoes and jackets to canvas and the skin of models. He also conducts an experimental art process he calls “The Sacred Art of Ori,” which involves one-on-one body painting and draws on Yoruba mythology and figures.

He has worked with brands including Nike, Equinox, and Kenneth Cole as well as celebrities including Alicia Keys, Taraji P. Henson, and Beyoncé.

His newest gallery show, which opened in New York in February, features illustrations on various items, including a “Black Panther” mask that sits in the center of the space. At the opening of his show, Senbanjo also chanted, “Wakanda forever,” a reference to the fictional homeland of the Black Panther.

“Art is a conversation starter,” he said. “It’s something that helps you see the artist and see how he sees the world.”

Sebanjo wants his art to start conversations around politics, religion, philosophy, and culture and hopes it provides an avenue for African Americans to feel connected to and proud of their heritage. But while Senbajo’s work showcases black resilience and is targeted toward Pan-African pride, he at first resisted the identity.

Growing up in Nigeria, Senbanjo felt pressure to suppress his creative ambitions and pursue career paths in law, medicine or engineering. He worked as a human rights attorney for the Nigerian National Human Rights Commission for a time, but he moved to New York in 2013 to create art.

“For every African that comes here, you’re first like, ‘No, I’m not Black … I’m Nigerian. I’m Yoruba. I’m from Lagos,'” he said.

But arriving in the U.S. in 2013 amid heightening conversations surrounding police brutality, Senbanjo said he felt devastated by the black death and white power that governed national conversations and compelled to address racial tensions and injustice through art.

His work began to include racial undertones and capture the emotions he felt when faced with the double standards he observed in the United States.

“The artist in me just started making art,” he said.

“A bullet doesn’t ask questions what race you are or what country you’re from,” he added. “These are my brothers and sisters.”

With films such as “Black Panther” celebrating the diversity of the continent, Sebanjo noted that more people could be interested in learning about the various cultures that lie in Africa. He said he wants to use his platform to prove that it’s “more than just history.”

But, he added that he didn’t want to be been seen as a representative of the entire continent.

“Honestly Africa is different to everybody,” he said. “Don’t just label on me like this African, African artist. I’m an artist.”