By Aryka Randall, Voice and Viewpoint

1951 was the year Alwin Holman became a Fireman in San Diego and unbeknownst to him, it would be the beginning of a legacy as one of the first Black Battalion Fire Chiefs in California.

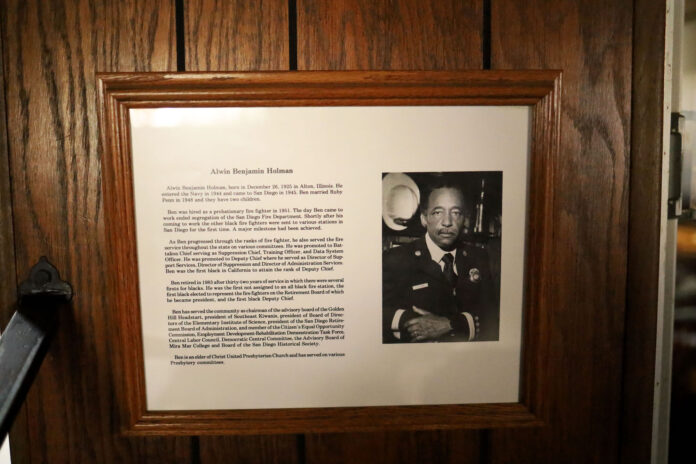

Born to Addy and Samuel Alwin Holman in 1925 in Alton Illinois, Alwin, also known as “Ben”, lived with his parents and siblings until he ventured out for work on his own at the age of 18. His journey was cut short when he was drafted to the Navy for World War 2 and his life was put on hold for two years while serving the country.

Upon completion of service, he joined USPS to work as a mail carrier which would later be where he stumbled upon the idea of becoming a Firefighter.

“There was a guy I used to work with who knew someone in the Fire Department and he kept telling me how good his job was and how we should try it out because he could get us a recommendation from his friend. The Postal Service was changing and we didn’t like some of the new working conditions so we decided to give it a shot.”

Alwin and his coworker wasted no time leaving the Postal Service and trying their hand at becoming firemen.

25 years old and full of tenacity, Alwin took the entry exam to become a Fireman and passed with flying colors on his second attempt. From there he would be placed on a mandatory 90 day probationary period where his superiors would decide whether he was a good fit for the station or not.

There was still one obstacle in his way though. Every Black Firemen in San Diego was segregated and placed at Station 19 off of Oceanview. For whatever reason, they decided Alwin would be the first to train at station 14 which was a non Black station. Naturally this ruffled the feathers of a few who were already placed at Station 14.

“One day the Chief pulled me aside and told me they wanted me to train at Station 14 on 32nd and Lincoln. The Chief told me that I was going to be his Jackie Robinson of the Fire Department and that I would be one of the first Black Firemen to serve outside of Station 19.”

Alwin had to have four separate meetings with the Chief to solidify his spot after receiving backlash from one of the Firemen doing intake. Eventually, the Chief told the man hesitant to work with Alwin that if he didn’t like it, he could turn in his badge and leave. There were no more issues after that.

Once he was part of the department, he wasted no time climbing up the ranks as a Firemen. After one year he was promoted to a third class Firemen and a few years after that he was promoted to Engineer and was given permission to drive the Firetruck.

“I loved driving the truck. Sometimes I would hit a turn and the ladder would go flying and they would fuss at me to slow it down around turns” he recalls with a mischievous smirk.

Five years later, Alwin successfully worked his way up the ranks at Station 14 to become the Captain, and eventually he would go on to become the second Black Battalion Fire Chief in the state of California.

Alwin served for a total of 32 years as one of the only Black Firemen at his station which indirectly opened doors for others.

“Part of their efforts to integrate stations with me was because they wanted more Black Firemen in San Diego and they knew they couldn’t put them all at Station 19. They were actively looking for Black Firemen to join but not many wanted to because of the job being so dangerous. Usually when a house is burning, everyone is running out, not it. But we did have a few join later down the line.”

While there were only a few of them, the Black Firemen who did exist stayed tight knit by way of the International Association of Black Professional Firefighters, and the Black Firefighters Association which has subgroups nationwide. To this day the Firemen who came after Alwin call him “Chief” and talk about the ways watching him go up the ranks inspired them to be fearless, and do the same.

Presently, only 8.4% of the Firemen in the U.S. are Black and their presence lacks visibility in the public eye at times, making it hard for little Black boys to see themselves as Firemen. Black Firemen do exist though, and hopefully stories like this that share their long history of being a part of the Fire Department will help them see that.

For more information on the Black Firemen’s Association and IABPFF visit the links below: