By Maya Pottiger, Word In Black

One of the recurring education headlines over the last year has been America’s unprecedented teacher shortage — especially as Black teachers quit at previously unseen rates.

Plenty of experts have ideas about how to end the mass exodus of educators from the classroom, but Eric Duncan, the assistant director of P-12 policy at The Education Trust, says there’s a solution we need to talk about more: If we had better recruitment success bringing and keeping Black educators in the classroom, the same shortage issues wouldn’t exist.

“If we want to address teacher shortages, teacher diversity is not only a key lever,” Duncan says, “it could be the key lever to addressing some of the long-term chronic shortages that affect some of our most vulnerable schools and student population.”

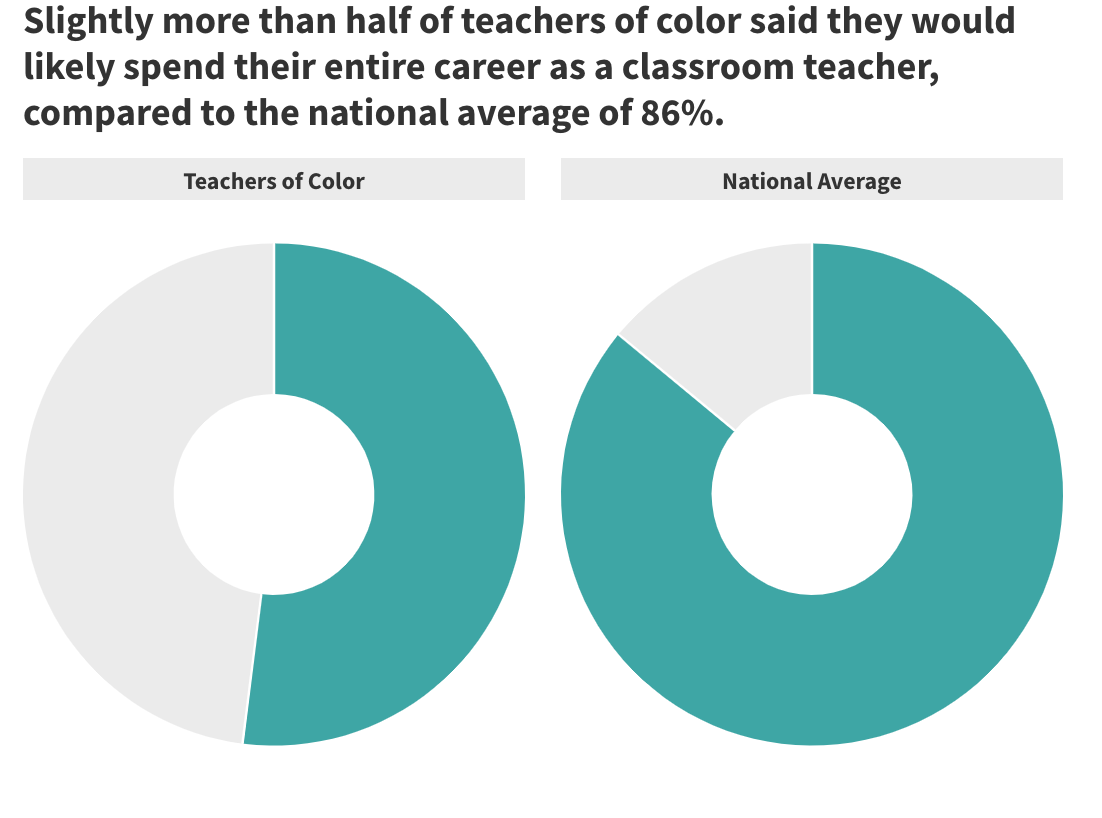

In the Education Trust and Educators for Excellence joint 2022 Voices from the Classroom report, results showed that 86% of teachers nationally said they would spend their entire career as a classroom teacher, but that number dropped to 52% when looking only at responses from teachers of color.

Unlike their white colleagues, Black educators don’t get to take for granted that they belong in the classroom. They don’t always have a peer, leader, or someone who will advocate for them or mentor them. Black educators also work in environments that aren’t necessarily welcoming, respectful, or culturally affirming.

“All those stresses contribute to their perception that this profession isn’t something that they can stay in and be successful,” Duncan says.

The Push for Nuanced Policy Solutions

Though boosting teacher diversity might seem like a new push, the idea’s been raised for the last 30-40 years, Duncan says. However, instead of simply saying that we need more teachers of color in the classroom, policy makers are now peeling back the layers to look at why the pipeline of new teachers isn’t sustainable.

“The conversation has become a little bit more nuanced,” Duncan says. “It’s been elevated as a priority.”

Research has proven that students of color who have teachers — and principals — who look like them achieve higher academic success, including higher reading and math scores. They also have higher high school graduation rates, and are more likely to enroll in college. But it’s not just students of color who benefit from having teachers of color — white students benefit socially, emotionally, and academically, too.

“If we grew our teachers at a faster rate, and teachers of color — specifically Black teachers, and even more specifically, Black male teachers — we would see a serious pivot in our American school system,” says Dr. Fedrick Ingram, secretary-treasurer of the American Federation of Teachers.

It’s Not as Easy as Raising Salaries

It’s no secret that teachers don’t get paid enough. But in most surveys of Black educators, earning a higher salary is not usually the top strategy for recruitment or retention.

However, the narrative shouldn’t be that Black educators don’t want to get paid more, Duncan says. Instead, it shows that Black educators face so many challenges at work, that when given an opportunity to share, higher pay doesn’t land at the top.

For many Black educators, going to work every day puts them in a situation where they’re not looked at in a positive light, they can’t be themselves, and they have to take on roles and responsibilities that their colleagues don’t.

“Of course, those are the things that I’m going to bring up as really important to change because they’re affecting my ability to even be a strong professional,” Duncan says. So instead of looking at it as Black educators don’t want to get paid, because they do, it’s more that “they have so many other challenges that are unique to being a Black educator— or the only Black educator in the classroom — that they are elevating those issues when they actually have an opportunity to share that.”

It also comes down to the reason that people go into teaching: They want to make a difference. And when they face obstacles like increased class sizes and secondhand books, they lose autonomy in the classroom. There needs to be less interference so there are more “lightbulb moments,” Ingram says, and more of the magic that happens between a teacher and a student.

“These are people who are marketable and who can do other things but want to be in our classrooms,” Ingram says. “So yes, they need the pay, but they also need the respect.”

Black Teachers Want Expanded Loan Forgivenes

In a 2022 study, RAND Corporation asked teachers of color about strategies to recruit and retain a more diverse K-12 workforce. The top practice Black teachers cited was expanding student loan forgiveness, with 67% prioritizing this strategy compared to 58% of all teachers of color.

Recruiters from school districts often make the mistake of assuming everyone is starting on an even playing field, El-Mekki says. When they graduate from college, Black teachers often owe twice as much in student loans than their white colleagues. This means that when early-career Black educators are hired by underfunded districts with lower salaries — which they often are — they’re put in the position of using money they don’t have to pay for critical things, like classroom supplies, out-of-pocket.

Though the Biden administration helped ease the loan burden, there is still more work that needs to be done to help Black teachers become debt free and financially stable.

“Student loan and debt forgiveness is one of the things that we have really got to do to not only recruit new teachers, but to retain the teachers that we already have,” Ingram says. “We’re looking for more relief as we move along in this political process.”

Teachers of Color Value Professional Development and Mentorship Opportunities

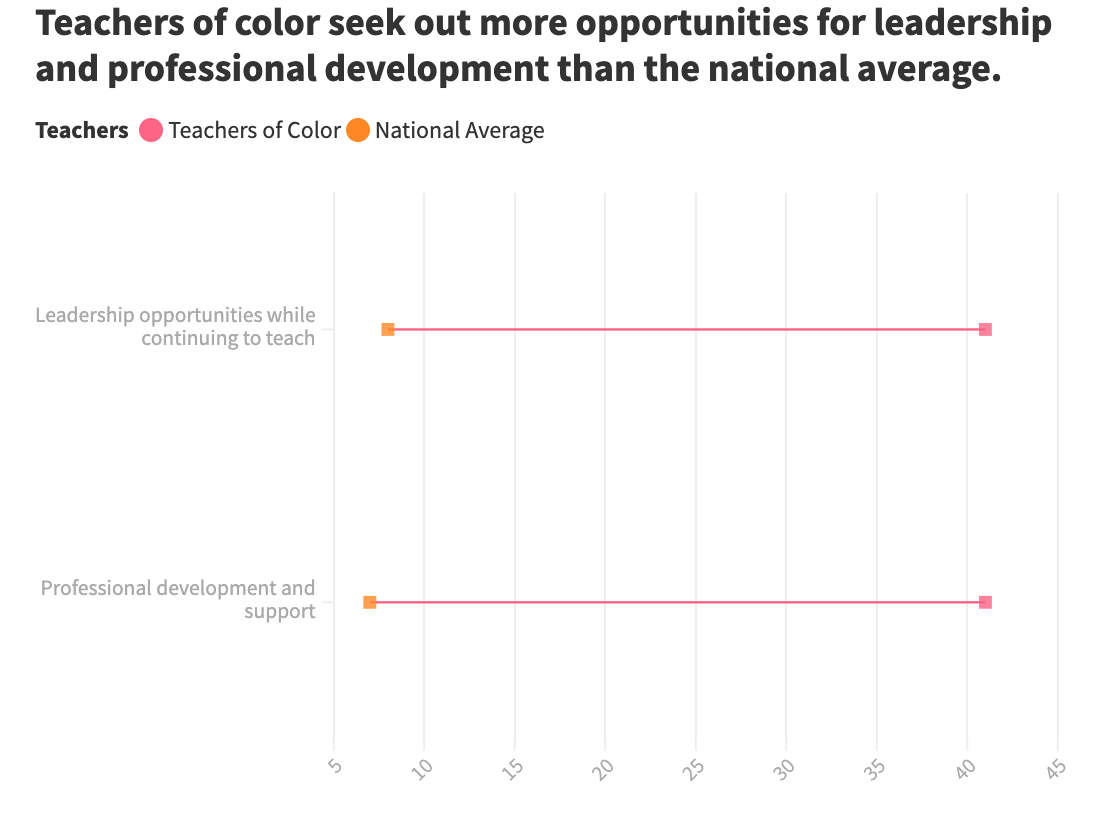

In terms of things that would keep them in the profession, two of the areas where teachers of color most differed from the national average of all teachers were when it came to ways to further their careers.

While only 7% of all teachers said they value more professional development and support, 41% of teachers of color highlighted this as a retention solution. Similarly, 8% of the national average sought leadership opportunities while continuing to teach compared to 41% of teachers of color.

Teachers often want more decision-making authority and influence in schools. White teachers are more likely to get those opportunities because they’re more easily funneled into the pipeline through other instructional opportunities they have in the building. Black teachers are more likely to be tapped for positions that look at discipline issues or cultural competence or equity, so when principal and superintendent positions open up, Black teachers aren’t in the running because they haven’t had instructional leadership roles.

“If you’re not provided the opportunity or seen as somebody who can bring intelligence in the traditional norm,” Duncan says, “you’re not necessarily tapped to be the next school leader or principal or whatever the sort of leadership position is.”

Among other popular strategies were a variety of mentorship and preparation initiatives.

For example, residency programs, where educators spend up to a year teaching in a high-need district and completing coursework, have been show to lead to more racially diverse graduates who stay in the profession for longer periods of time.

In Pennsylvania, El-Mekki’s group worked with the Pennsylvania Educator Diversity Consortium to create a retention toolkit, and one of the more popular methods is using a cohort model to ease some of the initial loneliness and isolation. They also recommend creating opportunities for teachers of color to convene and be able to positively impact the school policies, ecosystems, and curriculums.

Another idea was creating more mentoring opportunities for teachers of color, especially a peer-to-peer strategy that matches new educators with veterans. And, encouraging districts to partner with diverse teacher preparation programs to diversify the group of prospective teachers, was popular among 51% of Black teachers.

“Those have been more successful in recruiting and preparing Black educators because of those built-in supports,” Duncan says.

More Recruitment and Retention Strategies

There are a lot of different efforts around the country to recruit and retain Black educators, and they take various forms.

A popular strategy is grow-your-own programs, which are community-based efforts to support and encourage students through the process of becoming an educator. For example, the American Federation of Teachers runs a program in New York that creates a pipeline of students that are supported and nurtured throughout high school to get their education degrees from Montclair State University.

Not only are they surrounded by “master teachers,” Ingram says, but they’re given internships and proper resources to know what to expect when they go into the classroom.

“That’s a model that we are pushing across the country,” Ingram says.

And, of course, there’s providing more funding to the teacher preparation programs at HBCUs, which produce around half of the Black teachers who work in public schools.

“If we know that these students are there, then we need to cultivate that,” Ingram says. “We need to add resources to that, and we need to build these students up so that they are the next generation and wave of young people who teach that next generation behind them.”

The Education Trust and Educators for Excellence joint 2022 Voices from the Classroom report also highlighted that teachers of color cite housing support as a key way to both recruit and retain teachers, with 73% of teachers of color saying this compared to the 32% national average.

This is working in Connecticut, which has a teacher mortgage assistance program that’s targeted toward teachers of color. Though it’s still relatively new, there are signs that it’s working, Duncan says, by slowly driving up the diversity of the workforce.

El-Mekki, who works with early-career teachers, says programs like this are critical. He’s heard of teachers who are essentially reliving their college dorm experiences by having to have multiple roommates to afford rent in or close to the communities they teach in.

“That is deeply maddening,” El-Mekki says. “Teachers are committed to working in this community, but they can’t afford to live there.”

Overall with years of training needed to work in a constantly evolving profession, teaching is tough. But many organizations are investing in resources to grow talent and create pipelines into the classroom and ensure people have what they need to stay.

“There’s no panacea out there to fixing the diversity in our classrooms,” Ingram says. “Teaching is the noblest profession, but it is also the hardest profession to master and to craft, to educate our most precious commodity and those are our children.”