By Charlene Crowell, Trice Edney Newswire

In mid-June the Federal Reserve, nation’s central bank, raised interest rates in hopes of curbing rising inflation and deterring a full-blown recession. Chief among its responsibilities, the Fed’s duty is to develop “appropriate monetary policy”.

For much of Black America, many would welcome money itself – funds to provide stable day-to-day living, the ability to get rid of debt without worrying whether families will have enough money to last the month’s expenses, and even a bit more left over to face what the future may hold.

Student debt remains a stubborn obstacle that prevents Black Americans from securing financial stability in the short-term and financial wealth in the long-term. According to The Institute on Assets and Social Policy, after 20 years in repayment, the typical Black borrower still owes 95 percent of their cumulative borrowing total, while similarly situated white borrowers have reduced their debt by 94 percent —with nearly half of white borrowers holding no student debt at all.

After more than two years of the COVID-19 pandemic complicating family finances, the ability of many working Americans to maintain economic stability is nearing a breaking point. Further, due to historic racial wealth inequities, these and other impacts are felt hardest by Black America in general and Black women in particular.

New research from the Center for Responsible Lending (CRL) analyzes how women’s finances have changed over the past two years. The study, entitled Resilient But Deeper in Debt: Women of Color Faced Greater Hardships Through COVID-19, shows how these women’s lives dramatically changed as a result of the pandemic and deepening student debt.

The report states that Black women faced a “double whammy of increased debt and decreased savings.”

CRL analyzed publicly available data and additionally commissioned four focus groups of ethnically diverse women with varied educational levels who lost their job or were furloughed during the pandemic.

For context, it is relevant to note that:

- Between December 2019 and March 2022, 1.2 million women left the labor force;

- Between February 2020 and April 2020, almost 22 million jobs were lost; and

- In 2021, Black and Latina women were twice as likely as white men to report being behind on rent or mortgage payments.

Overall, findings indicate the widespread disruption in employment due to the pandemic has had a profound impact on women, their families, and their finances, states the report. “While a typical white male borrower pays off almost half of his balance within 12 years of starting college, the balance of a typical Black female borrower grows by 13 percent.”

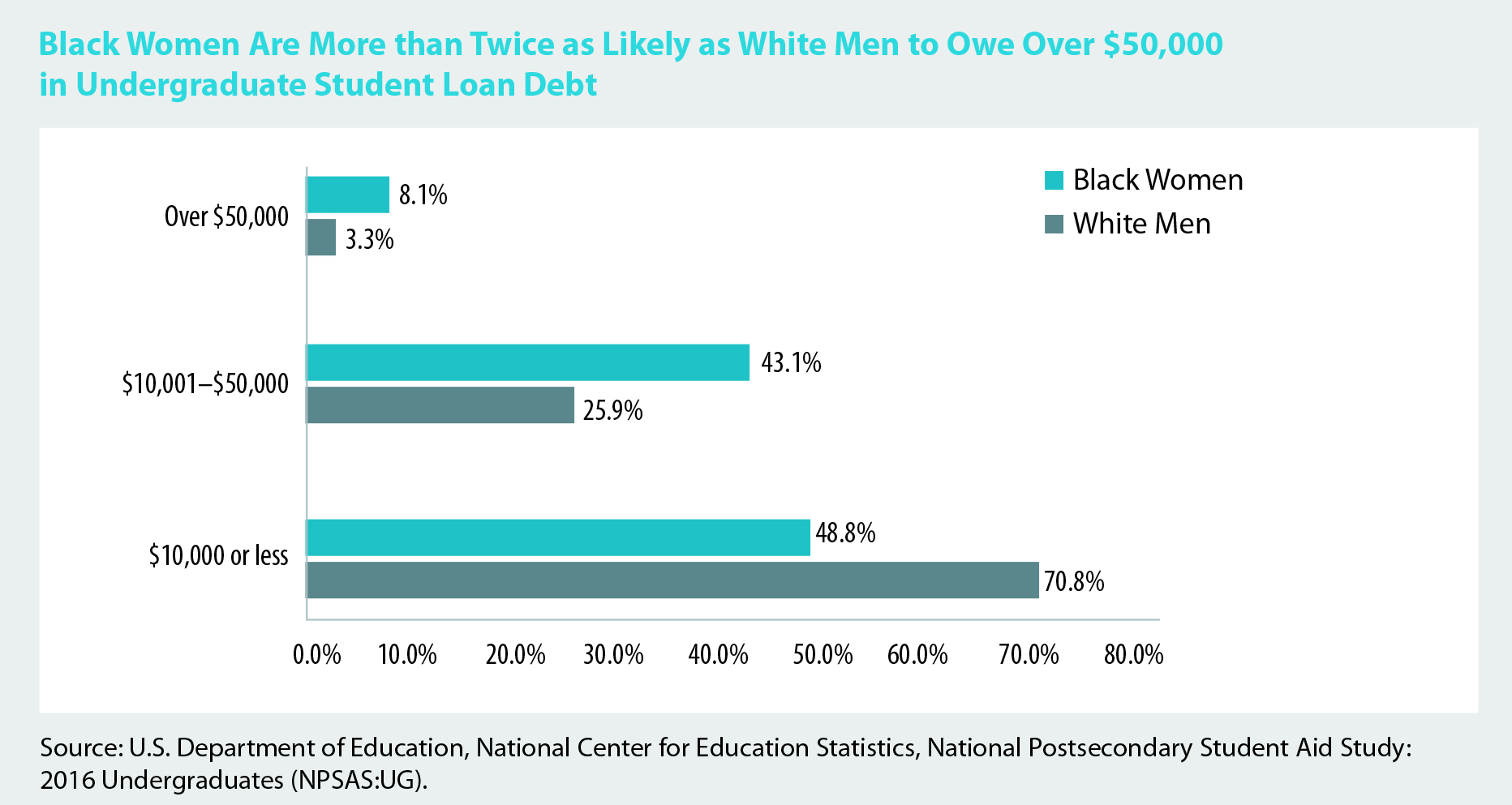

Further, about two-thirds of the $1.7 trillion federal student debt burden is borne by women. Black women are twice as likely to owe more than $50,000 in undergraduate student debt compared to white men. Both Black and Latina borrowers typically have higher loan balances than white women. Hence, student loan repayment challenges for women of color are higher and strain the ability to cover daily living expenses for their families, particularly due to rising costs of food and housing.

“Because of persisting pay disparities, and little or no generational wealth, women of color have fewer opportunities to pursue a debt-free education or to withstand an economic or personal crisis,” added Sunny Glottman, a CRL researcher.

Research found that 60 percent of Black women and 40 percent of Latina participants owed more than $50,000 in student debt. By comparison, only 29 percent of white participants owed more than $50,000 in student loan debt.

Although focus group participants found the current federal pause on payments and interest accrual helpful, few felt financially prepared to resume payments when the payment pause expires on August 31, and many foresaw worsening financial challenges.

CRL is among a growing number of consumer advocates calling for $50,000 of student debt forgiveness per borrower. Additionally, CRL also recommends greater higher education investments at both the federal and state levels to support public and private HBCUs.

For example, doubling the annual Pell Grant award that serves many students of color would keep better pace with the rising costs of college educations. Additional forms of support could provide research contracts and internships.

Implementing retroactively Income-Drive-Repayment (IDR) plans to remove lifetime debt repayments and offering improved access to the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program are additional federal actions that would relieve the nation’s unsustainable student debt.

Inaction on student debt relief must not be an option. Instead, policies must be implemented to relieve, as the report terms, “an albatross perpetuating a baseline of financial anxiety.”