(CNN) — Adrienne Keeler remembers struggling to stay awake in church on New Year’s Eve as a child while her family praised God for carrying them through another year.

Back then, Keeler said she couldn’t wait to get to the part of the church service where everyone said, “Happy New Year!”

“I just remember, thinking, ‘Man, I am tired,’” Keeler told CNN, adding that midnight was long past her childhood bedtime.

But now, the 35-year-old, who’s a member of Mount Zion Baptist Church in Triangle, Virginia, said she looks forward to attending “watch night” each year.

The Black American tradition of spending New Year’s Eve in prayer and fellowship dates all the way back to the Civil War. It’s deeply rooted in the long-awaited dawn of freedom for enslaved Africans and their hopes for the future.

“There is just so much that we’ve been going through over the past year. I have family members that aren’t making it into 2024,” Keeler said. “It’s just the remembrance of that and remembering in a positive way around positive people.”

Countdown to freedom

After Union troops halted the advance of the Confederacy in the Battle of Antietam, the bloodiest single day of the Civil War and in American history, President Abraham Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862. It declared that all enslaved people living in states in rebellion against the Union would be set free on January 1, 1863, the day Lincoln would sign the final document.

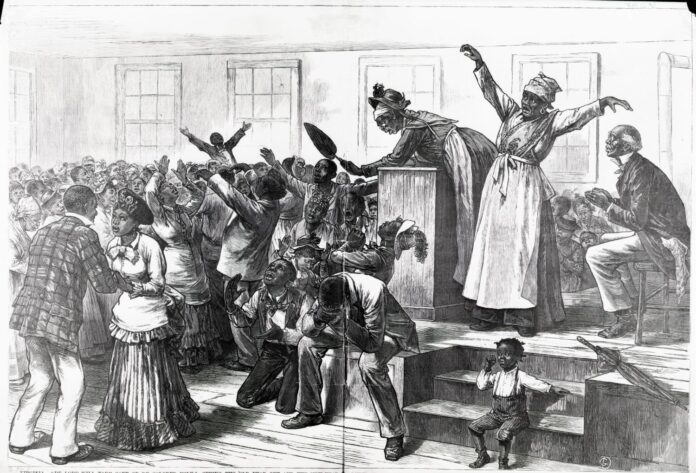

“People knew on December 31, 1862, that it was the coming of a new day,” Kate Masur, professor of history at Northwestern University, said. “So, the watch night tradition took on a new meaning and Black Americans in many places, in the free states, in the slave states, assembled for watch night meetings, celebrating the coming of freedom.”

Abolitionist Frederick Douglass was among those who gathered that watch night, or “Freedom’s Eve,” to anxiously await the New Year. Douglass, who legally gained his freedom in 1846, attended a watch night meeting at Tremont Temple in Boston, waiting for news that the Emancipation Proclamation had been officially signed, said Emily Blanck, associate professor of history and American studies at Rowan University.

“‘We were waiting and listening as for a bolt from the sky, which should rend the fetters of four millions of slaves’,” Blanck said, quoting from Douglass’ autobiography.

A formerly enslaved woman named Aunt Phoebe Bias attended a watch night meeting in Washington, DC, shortly before her death. Bias’ account of the service was retold in the 1942 book, “They Knew Lincoln,” by John E. Washington. The book was republished in 2018 with a new foreword by Masur.

According to Washington, Bias, who had been enslaved in Virginia, heard of a “big watch-meeting” on Dec. 31, 1862, at her church “where important White and colored men would speak about President Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation.”

Bias told Washington she decided to attend the service, which began around 10:00 pm with a sermon. Then, a copy of the Emancipation Proclamation was read out loud, according to her account.

As the church clock ticked closer to midnight, attendees cried and prayed for God to lead them from bondage, according to Bias’ account. They also prayed for Lincoln.

“They had prayed for freedom. That night it came,” Washington wrote, recounting Bias. “When the city bells rang in the New Year – the year of their freedom, men and women jumped to their feet, yelled for joy, hugged and kissed each other and cried for joy.”

Though true freedom would not be granted until the 13th Amendment was ratified on December 6, 1865, and slavery was abolished, the 1862 watch night services provided a glimmer hope for those who had been held in bondage for centuries.

The legacy of watch night

Today, Black Americans still gather in churches nationwide on New Year’s Eve, giving testimonies about situations they overcame and praying for blessings in the new year.

Tracy Oliver-Gary said she also remembers attending watch night service with her family as a child in Little Rock, Arkansas.

“We come from a history where most African Americans did not know how to read and write so things were passed down orally, passed down through tradition,” she said.

Oliver-Gary attends Mount Jezreel Baptist Church, which was established between 1865 and 1873 and is thought to be one of the oldest Black Baptist churches in the Washington, DC, area, according to church history.

She said she strives to attend a watch night service each year to do her small part to keep the tradition alive.

“You have the spiritual aspect about reflecting about God but there’s also the cultural historical aspect of preservation of African American culture … The Black church is, to me, the hallmark place of preservation of Black history of Black culture,” she said.

Over the years, watch night service traditions have evolved. Some congregations now begin and end services earlier in the evening. Since the pandemic, others have moved to a virtual format so that more congregants can attend from the safety of home.

But both Oliver-Gary and Keeler said the historical significance still remains. They also believe that watch night service, like other traditions in Black culture, should continue to be passed down.

“This concept of faith and this belief that although things may not be what you want them to be, that a better day is coming, that has been a thread throughout the lives of Black people in America,” Oliver-Gary said.

Keeler agreed and said Watch Night remains a powerful symbol and tradition for Black Americans because it underscores the power of hope.

“African American traditions, some of them are kind of dying just because some people don’t understand what they mean or culture about us,” she said. “This is our form of culture. We gotta keep it going.”