By Hazel Trice Edney, Trice Edney

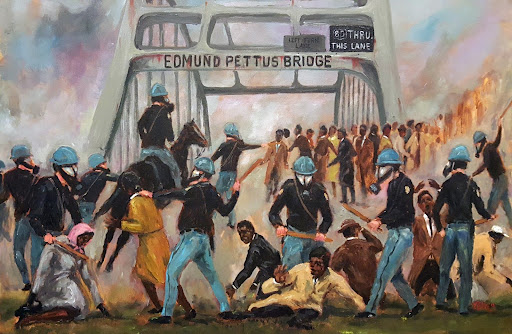

Thousands of Black people protested and many died at the hands of police, White supremacists and racists as they engaged in non-violent campaigns to win the right to vote. Still, America did not fully sit up and hear their cries until “Bloody Sunday”, March 7, 1965. On that day TV cameras showed protestors being brutally attacked and beaten by the Alabama State Police as they marched peacefully from Selma to Montgomery across the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

It was only then that the United States government took decisive action.

President Lyndon B. Johnson, a week after “Bloody Sunday”, adopted the words of the civil rights leaders and declared before the nation in a televised speech to Congress, “We shall overcome.” Within a few months, the United States Congress adopted the Voting Rights Act (VRA) of 1965 and it was signed into law by President Johnson on August 6 that year. In a nutshell, the VRA prohibited any activities by anyone to abridge the right to vote.

More than 58 years later, Black doctors on the front lines against racism in medicine across the U. S. had hoped that the revelation of racially disparate suffering and death amidst the Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) would become the “Bloody Sunday” for revealing the truth about health disparities in America and escalate the long struggle to end them. But that has apparently not happened.

Dr. Sullivan is among leading Black physicians and HBCU administrators who agree that health disparities in the Black community – and the racism at the root of it – has been revealed to be far worse than anyone thinks. They say the disparities still must be dealt with through racial and cultural coalitions, increase in Black medical professionals and strengthening of public policies.

“When an additional stressor like COVID-19 or the Coronavirus presents itself, we already have a subscript in American life where whatever is bad happens worse to African-Americans,” says Dr. Rahn Bailey, chief of the Psychiatry Department at Louisiana State University. We have less health care access; we have fewer hospitals in our communities; we have less access to providers or specialists; very often we get less optimal medication or management. We have data to support that.”

The data indicates racial disparities across the board:

- Exact numbers on COVID 19 infections, hospitalizations and deaths are fuzzy, largely because states initially did not track the pandemic by race. But, the Kaiser Family Foundation reported last year that though racial disparities narrowed as the pandemic subsided, during the surge associated with the Omicron variant in winter last year, disparities in cases once again widened with people of color, including African-Americans at 2,937 per 100,000 people, compared to cases among White people at 2,693 per 100,000.

- This number is astronomical given that America is approximately 12 percent African-American and 59 percent White. The New York Times reported that “during the height of the Omicron variant, COVID killed Black people in rural areas at a rate roughly 34 percent higher than it did white people.”

Despite the COVID 19 disparities that drew a new focus to the issue of racial health disparities, ending the racial gaps in deaths is still a struggle, says Yolanda Lawson, MD; an obstetrician and gynecologist. She pointed out that after the videotaped killing of George Floyd by now imprisoned Derek Chauvin, “everybody got onto the equity bandwagon. Yet, here we are still talking and we know that there’s still this wide gap.”

In addition to racism, pure and simple, researchers have often laid health disparities at the feet of what is called “social determinants;” which, in a nutshell, means common lifestyles of particular groups of people that often stem from systemic racism. Likewise, economic and social circumstances such as poverty and food deserts often lead to illnesses like heart disease, diabetes and cancer.

“And even when there are solutions such as the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which assured that approximately 20-35 million adults, who previously had been uninsured, received coverage by Medicaid, there would still be cracks in the system,” says, Dr. Randall Morgan, an orthopedic surgeon who is president/CEO of the Cobb Health Institute, the research arm of the National Medical Association.

Despite the glaring disparities, advocates on the front lines have often run into brick walls when trying to call attention to them and trying to raise funds to end them.

For example, Bill Thomas Jr., an advocate for proton therapy treatment at the Hampton University Proton Therapy Cancer Institute, has been leading a near-futile battle for more money to end cancer disparities as the HBCU’s associate vice president for governmental relations.

In an interview, Thomas pointed to observations made by former Virginia Gov. L. Douglas Wilder, concerning the Commonwealth’s underfunding of HBCUs – both public and private. In a recent op-ed editorial, Wilder quoted a Goldman Sachs report in the Richmond Times-Dispatch titled, “Historically Black, Historically Underfunded.”

Wilder’s op-ed stated that “public HBCUs have 54% less in assets per student” than public predominantly White universities while “private HBCUs have 79% less than private” predominantly White universities. Like Wilder, Thomas asks the question, “‘why the legislature and the current administration cannot redress the wrongs of legal discrimination?'”

Support to undergird the programs of HBCUs could indeed be one of the key answers to the problem of health disparities, Lawson says. With an increase in Black doctors, more hospitals in Black neighborhoods and more medical programs at HBCUs, health disparities could begin to close, she said.

An NMA program called Project Impact 2.0 has two goals, Lawson says – first, to increase the number of African-American researchers and to increase the numbers of Blacks included in research studies. But, just like with the civil rights successes, Lawson adds, the battle will take people of all races and walks of life working together.