By Calvin Schermerhorn, Arizona State University

Twenty-two-year-old Sam Watts saw the Virginia coastline vanish while he was aboard a domestic slave ship in the fall of 1831. Andrew Jackson was president, and slave traders had bought Watts for US$450 (about $14,500 in 2022 dollars). They were ripping him from multiple generations of his loved ones for a voyage of no return.

After the ship docked at New Orleans three weeks later, Edmond J. Forstall, a banker and entrepreneur, purchased Watts for $950. His new owner put Watts to work making barrels in the new Louisiana Sugar Refinery – the world’s largest operation of its kind at the time.

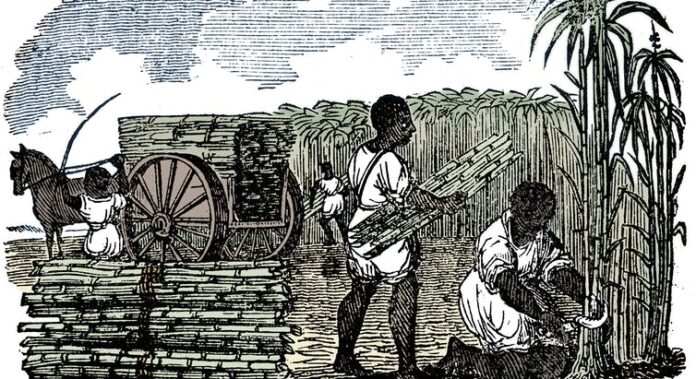

Watts labored under an overseer’s lash, but he may have felt less unfortunate than Louisiana’s 36,000 enslaved people forced to work on plantations producing the sugar that went into his barrels. Growing, cutting and processing domestic sugar cane took an even deadlier toll than producing cotton or tobacco.

Watts’ unpaid work fed a supply chain with tragic human costs. Most Americans today would surely like to think that consumers who knew their sugar was grown and processed by enslaved people living in the United States would refuse to buy it. But the historical record points to a greater opposing force: the rise of American capitalism, which before the Civil War was fueled by unpaid labor.

Government support for sugar started early on

Louisiana growers started producing molasses in the 18th century and granulated sugar by 1795. Output increased after the U.S. bought Louisiana from France in 1803. The federal government was already protecting domestic sugar with a tariff on imported sugar.

By the 1830s, strong demand and creative financing from international investors were also bolstering Louisiana’s sugar sector. The same year Sam Watts was bought and sold, Sen. Henry Clay wrote that “a repeal of the duty would compel the Louisiana planter to abandon the cultivation of the sugar cane.”

Sugar had by then been transformed from a luxury into a wildly popular ingredient that was integral to the American diet.

Molasses and cane sugar were as American as apple pie. They flavored everything from Boston baked beans to syllabub – a dessert of sweetened whipped cream mixed with cider or wine.

Unfortunately, the historical record indicates that most Americans who bought a quart of molasses or pound of refined sugar crystals either didn’t know or didn’t care very much about the struggles of Sam Watts and tens of thousands of other African Americans like him. Sugar was a prestige item, signaling wealth and refinement.

Luis Sinco/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

British abolitionists offered a model

Starting in the 1780s, British abolitionists had urged and organized consumer boycotts to end the transatlantic slave trade. Sugar was its engine, and activists like the poet Robert Southey condemned those who “sip the blood-sweeten’d beverage” with a clear conscience.

They published pamphlets and circulated petitions urging consumers, particularly women, to stop buying sugar made by enslaved people. Children got involved, too.

In 1791 in Manchester, England, some 300,000 people promised to boycott sugar sourced from the Caribbean. Sales dropped dramatically. Abolitionists flooded Parliament with petitions to end the transatlantic slave trade.

Britain made its subjects’ involvement in the trade illegal in 1807. Yet sugar producers in the Caribbean, including in Jamaica and Cuba, continued to force hundreds of thousands of enslaved people to make sugar.

Elizabeth Heyrick, a Birmingham philanthropist, led an even more successful English boycott of West Indian sugar in the 1820s.

British boycotts made at least a symbolic difference, because abolitionists got consumers to empathize with enslaved workers at a time when national interests were turning away from the sugar industry because of shifting international alliances.

The limits of consumer pressure

Although the U.S. banned the landing of foreign captives destined for enslavement in 1808, it let the domestic slave trade flourish for another five decades.

U.S. growers were competing mainly with the Cuban sugar producers who could still import African captives. Newly enslaved people often arrived on American-owned vessels.

Free African American and white Quaker abolitionists sought to underscore the connection between unrequited toil and the abundance it produced. Before supply chain management existed as a systematic process, those who worked to abolish slavery pointed out that the dollars spent on sugar fed the forced labor and degradation of Black people who made and processed sugar and other commodities.

To that end, Quakers formed the Free Produce Society of Pennsylvania in 1827 to combat slavery in supply chains furnishing consumer goods.

In 1830, African American abolitionists established their own similar organization, the Colored Free Produce Society of Pennsylvania. Its 500 members used their collective power to demand cotton, sugar and tobacco be made by free workers. Judith James and Laetitia Rowley, two Black Philadelphians, co-founded another group, the Colored Female Free Produce Society soon after.

That organization’s members were connected with Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, Philadelphia’s hub of abolitionist and community organizing. It urged consumers to use their buying power to free enslaved people.

In 1834, Philadelphia’s most successful Black businessperson, William Whipper, opened a free labor store next to Mother Bethel church. In New York, African American abolitionist David Ruggles sold only free sugar and encouraged others to follow suit.

By 1838, the Free Produce Movement, as it was called, had coalesced as the American Free Produce Society.

But those scattered individual acts of conscience failed to force the sugar industry to stop relying on forced Black labor. U.S. abolitionists’ efforts to inform the public and organize boycotts also failed to stop growing demand, because sugar prices fell until the Civil War disrupted the popular commodity’s production.

Victor De Schwanberg/Science Photo Library via Getty Images

Sugar demand climbed

Rather than cut back, Americans consumed more and more sugar.

When Watts went to work in the Louisiana Sugar Refinery, the average U.S. resident ate 13 pounds of it per year. By 1850 the total had surged to 30 pounds.

In many places, emancipation didn’t stop coercive labor practices. The relationship between emancipated workers and the sugar barons and other planters who employed them still approximated slavery.

Sugar workers in Thibodaux, Louisiana, for instance, lived in many of the same quarters as they had before the Civil War. When they unionized and tried to strike for better wages in 1887, white townspeople massacred the farmworkers and their relatives, killing 60.

In Texas, sugar plantation owners used convict laborers to grow and process their sugar cane. Many prisoners forced to make sugar were teens convicted of minor offenses, often by Jim Crow courts.

The 2019 discovery of 95 grave sites of African American sugar workers buried on a prison farm in Texas offered a glimpse of the toll sugar work took on Black workers, many of them children.

The Free Produce Movement may have failed to curb the human rights atrocities occurring in the 19th-century sugar supply chain. But many activists are still drawn to the connection U.S. and British slavery abolitionists made between consumer purchasing power and the possibility of improving labor conditions.

This article is part of a series examining sugar’s effects on human health and culture. Read the series at theconversation.com.

Calvin Schermerhorn, Professor of History, Arizona State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.