Mary McLeod Bethune called him “the tallest tree in our forest,” and he was arguably the most famous African American man in the world during the early 20th century. Actor, singer, scholar, athlete, and human rights activist Paul Robeson is the subject of the La Jolla Playhouse’s upcoming production, “The Tallest Tree in the Forest,” which opens Thursday, October 10. It is a deep and penetrating look at this complex 20th century Renaissance man, whose unparalleled artistry allowed him to enjoy wealth and worldwide fame, while his outspoken political views on race and class also made him a lightning rod, eventually leading to his being hounded by the FBI and CIA and blacklisted, a series of medical problems including a stroke, and, tragically, his eventual exit from public life.

Daniel Beaty wrote and stars in this world premiere one-man-show with musical accompaniment that features excerpts from some of Robeson’s signature songs, including “Ol’ Man River” and “Steal Away.” On a recent visit to San Diego, the award-winning playwright/actor/director/ took time to reflect on his personal journey to bring Robeson’s story to the stage. For Beaty, the artist’s journey to understanding the man and his legacy today comes from a place much deeper than simply a performance endeavor. He explains, “Robeson had the stroke that many said ended his life on December 28, 1975, the same day that I was born. That has an emotional and poetic resonance for me.” Add to that Beaty’s own core view, like Robeson’s, of the artist as an agent of change, and a vision of storytelling as a tool to empower individuals and communities and you begin to understand the passion that fuels through this project.

“One of the big questions I’m asking is what about the character caused him to sacrifice literally everything for what he believed in,” says Beaty. “And with a life as mammoth as his, the challenge is how to tell the story, not just as a series of events, but to delve into the mind, heart, and soul of a human being and to try to understand the man inside of these events.”

One of the framing devices of the play, says Beaty, is seeing Robeson at the end of his life sitting in the living room of his sister’s home on the day that he had the stroke, fighting for his own memories and questioning if he will be remembered in history or if he will he be erased. As the metaphor of the tallest tree looms, he asks, ‘how deep are my roots in this American soil? Will I be remembered or will history uproot me?’

Beaty is no stranger to the artist’s journey. A graduate of Yale University and the American Conservatory Theatre, and adjunct faculty at Columbia University, he has had numerous plays produced nationally and has authored several children’s books. “For me, Paul Robeson epitomizes the artist/activist in the vital and unique role he plays in social discourse,” Beaty explains. “That is my belief and part of my purpose as an artist.” He speaks openly about his own life and background, because, he says, “it has influenced why I create what I create.” Beaty grew up in a troubled household where his father and older brother battled drug addictiuon, his father spending the majority of Beaty’s youth in prison, “A large part of how I saw myself and my possibilities was influenced by models of black men in my home.” A spark was ignited in him, however, in third grade when his teacher played a video of Dr. King’s “I Have A Dream” speech. “Seeing a man who didn’t look so different from my own father or my brother,” he recalls, “who was using words to inspire masses of people” inspired the young student. He told his teacher, “I want to do that,” and it wasn’t long before the young Beaty was traveling to Kiwanis, Rotary, and NAACP conventions throughout the country delivering his own inspired speeches. As he grew and was exposed to other worlds and environments, he saw that the problems that existed in his own milieu existed in urban centers across the country. “I began to understand the legacy of slavery, race and class in this country and how that has impacted family structures.” Thus began his own journey to create works exploring how to speak boldly about such barriers and how to tear them down; and even more, he adds, “putting into the world new models of possibility who had deep understandings of race and class and found ways to heal and to do extraordinary things. Paul Robeson was a real example of that. Whether he was speaking on behalf of Welsh minors or the African colonial freedom movement or the labor movement in the United States, or race relations in post Jim Crow America he was always up to that same project.”

The conundrum remains, however, that for such a prominent figure of the 20th century, why is Robeson so dimly remembered and why has he been so marginalized. In what portends to be a compelling and eloquent exploration, Beaty’s “The Tallest Tree in the Forest” promises to shed new light.

“Daniel Beaty is a powerhouse of a performer and a supremely talented playwright, and his new piece sits squarely at the center of the Playhouse’s mission to serve as a home for artists to develop new work,” says Christopher Ashley, the theatre’s artistic director. “In Paul Robeson, an iconic figure who was as galvanizing as he was polarizing, Daniel has found the perfect subject to inhabit in this probing piece about the power and responsibility of a great artist.” Directed by Moisés Kaufman, the show runs from October 10 – November 3. For ticket information, call (858) 550-1010 or visit www.lajollaplayhouse.org

Story by Barbara Smith

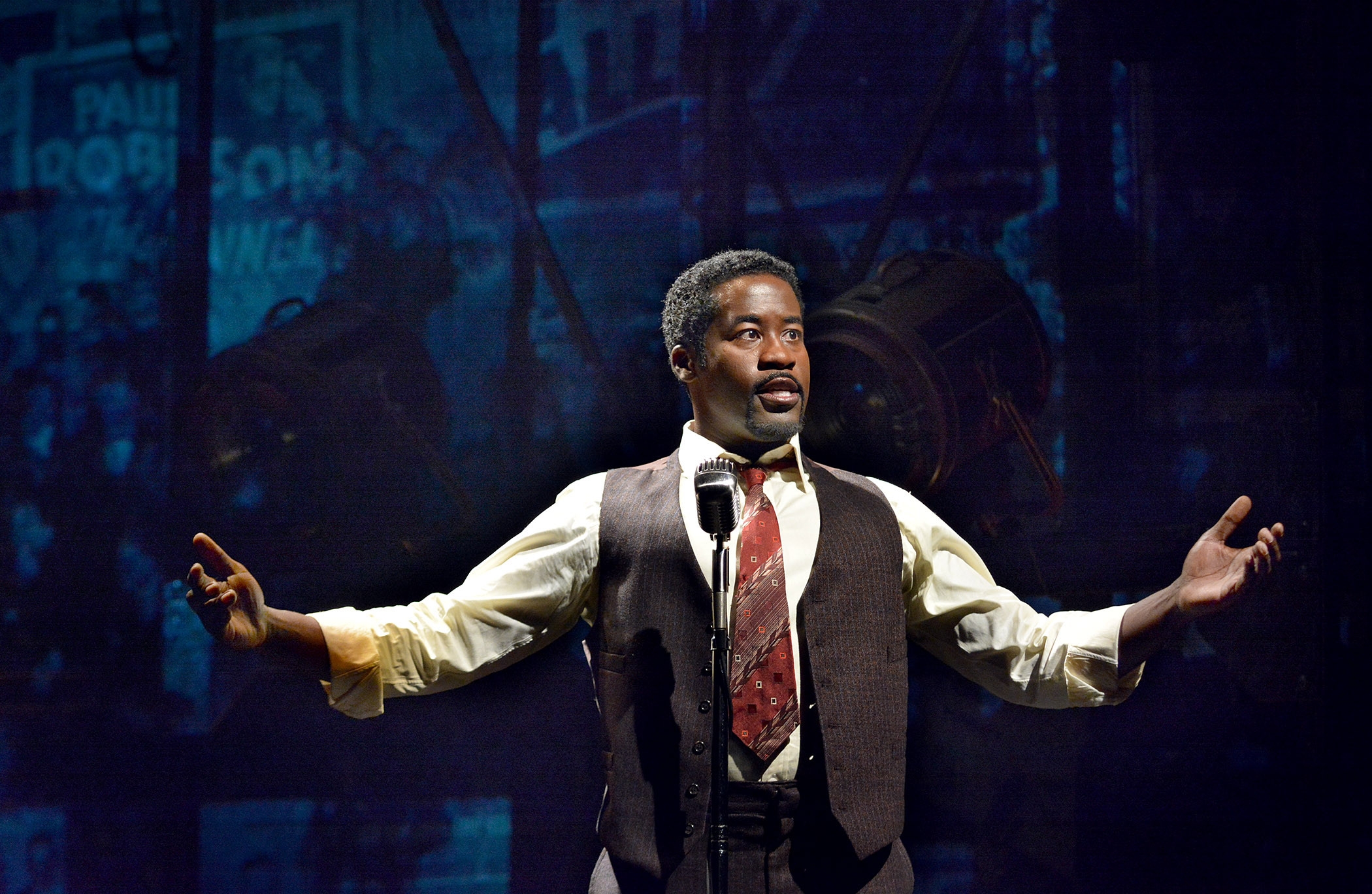

Photos Caption: Daniel Beaty, writer and performer of La Jolla Playhouse’s world-premiere production of THE TALLEST TREE IN THE FOREST, directed by Moisés Kaufman, running in the Sheila and Hughes Potiker Theatre October 10 – November 3; photo by Don Ipock, courtesy of Kansas City Rep.