By Farnoush Amiri, Associated Press

Nikiesha Thomas was on her way to work one day when she told her sister that she was thinking about getting involved with domestic violence prevention.

The idea gave Keeda Simpson pause. Her younger sister had never mentioned anything like that before, and she was bringing it up in a phone call just days after filing for a protective order against her ex-boyfriend.

It was their last conversation.

Less than an hour later, Thomas’ ex-boyfriend walked up to her parked car in a southeastern neighborhood of the nation’s capital and shot through her passenger window, killing the 33-year-old.

It’s cases like hers, where warning signs and legal paperwork weren’t enough to save a life, that lawmakers had in mind this summer when they crafted the first major bipartisan law on gun violence in decades.

The measure signed by President Joe Biden in June was part of a response to a harrowing string of shootings over the summer, including the slaying of 19 children at an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas.

The package included tougher background checks for the youngest gun buyers and help for states to put in place “red flag” laws that make it easier for authorities to take weapons from people adjudged dangerous.

Also tucked into the bill was a proposal that will make it more difficult for a convicted domestic abuser to obtain firearms even when the abuser is not married to or doesn’t have a child with the victim.

Nearly a decade in the making, lawmakers’ move to close the “boyfriend loophole” received far less attention than other aspects of the legislation. But advocates and lawmakers are hopeful this provision will save lives and become a major part of the law’s legacy.

“We have so many women killed — one every 14 hours, from domestic partners with guns in this country,” Sen. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn., a longtime advocate for the proposal, said before passage of the bill in June. “Sadly, half of those involve dating partners, people who aren’t married to someone, but they are in a romantic relationship with them in some way.”

Federal law has long barred people convicted of domestic violence or subject to a domestic violence restraining order from being able to buy a gun. But that restriction had only applied to an individual who is married to the victim, lived with the victim or had a child with the victim. As a result, it missed a whole group of perpetrators — current and former boyfriends or intimate partners — sometimes with fatal consequences.

At least 19 states and the District of Columbia have taken action on this issue, according to data compiled by Everytown for Gun Safety. Klobuchar and domestic violence advocates have worked for years to do the same on the federal level, with little success.

The struggle over defining a boyfriend in the law remained difficult to the end. Negotiations in Congress nearly broke down over the provision. The same thing happened in March when a similar bipartisan effort to reauthorize a 1990s-era law that extended protections to victims of domestic and sexual violence passed only after Democratic lawmakers took out the loophole provision to ensure Republican support.

“That was the toughest issue in our negotiations,” Sen. Chris Murphy, D-Conn., a lead negotiator of the gun package, said of the loophole proposal. “The biggest discussion that took us a long time at the end was around the question of how you would get your rights back after you had been prohibited.”

Murphy and other Democratic negotiators were able to persuade Republicans by including a narrow path to restoring access to firearms for first-time offenders after five years, only if they are not convicted of another misdemeanor for violent crime. For married couples, and those who have had a child together, the firearm ban is permanent.

To some advocates, more change is still needed. The legislation only partially closes the loophole because dating partners subject to a domestic violence restraining order, as in Thomas’ case, are still able to buy and maintain access to firearms.

“It will for sure save lives. But also to be clear, this is a partial closure of what’s known as the boyfriend loophole. There’s still a lot of work to be done,” Jennifer Becker, the legal director and senior attorney for Legal Momentum, a legal defense and education fund for women, told The Associated Press.

Federal crime data for 2020 showed that out of all murder victims among intimate partners — including divorced and gay couples — girlfriends accounted for 37%, while wives accounted for 34%. Only 13% of the victims were boyfriends, and 7% were husbands.

In 2018, a group of researchers who looked at intimate partner homicides in 45 states from 1980 to 2013 found that when firearm prohibitions linked to domestic restraining orders included people who were dating, deaths dropped by 13%.

“It suggests that when you cast that wider net, by covering boyfriends, you are able to cover people who are more dangerous and potentially save more lives,” April Zeoli, a researcher at the University of Michigan who was part of that study, told the AP.

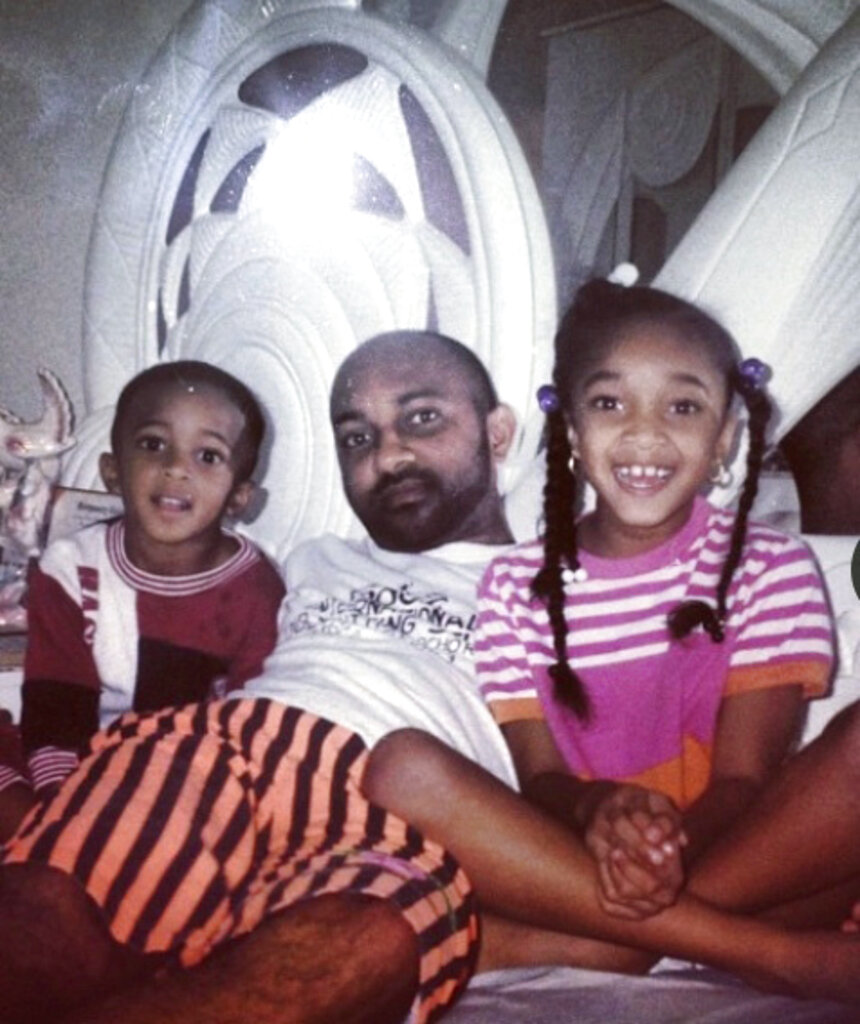

Thomas’ family hopes the changes in the law will save lives and ensure their daughter’s death wasn’t in vain. They say Thomas was doing everything she could to protect herself when she left her yearslong relationship with 36-year-old Antoine Oliver in late September 2021.

It was only after her death in October that her family members found out that the protective order Thomas had filed three days earlier, detailing how her former partner had access to firearms and she felt unsafe, was never served. Sheriff’s deputies in Prince George’s County, Maryland, where Oliver lived, had been trying to reach him by phone.

When law enforcement finally reached Oliver, he told them he would come to accept service of the judicial order the following day. Instead, authorities said, he killed Thomas that day before fatally shooting himself.

“Some days I just sit and review the paper she had filed with the court just a few days prior and just think, what else could she have done to protect herself?” said Nadine Thomas, her mother. Gilbert Thomas, her father, said his daughter did everything she was supposed to do, but it was the system that failed her.

“She feared for her life and what did the police do? They called him and made arrangements for him to come to pick up the order,” he said. “There was no urgency placed on it.”

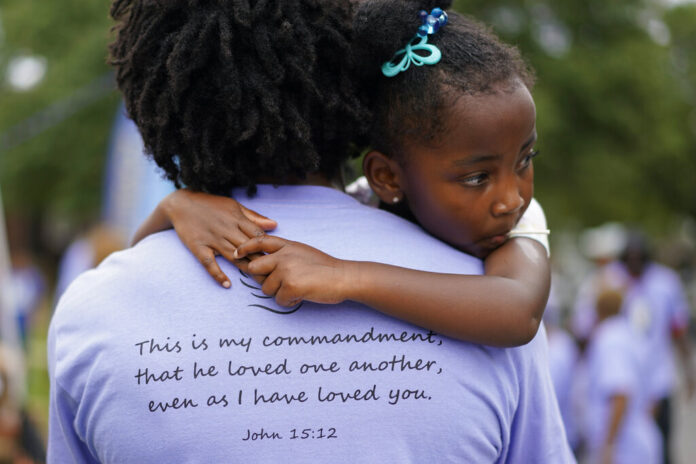

But now the family is bracing for the anniversary of Thomas’ killing. The weight of grief is heavy, particularly for her 11-year-old daughter, Kylei, whom Thomas had from a relationship before she met Oliver.

In the months before her death, Thomas had been making plans to buy a home for her and her daughter. She was saving up from her job with the D.C. Office of the State Superintendent of Education, where she was assigned to an intervention program to help some of the district’s most challenged students.

“We really were starting to map out some things and it just got taken away,” her sister, Keeda Simpson, said. “One of the last things we talked about was her wanting to evoke change for other women.”

“I’m going to do whatever it takes — even if it’s a small thing — to help someone else that’s in her situation, not to lose their life,” she added.

___

Associated Press writer Susan Haigh in Hartford, Connecticut, contributed to this report.