“Before this website, it was impossible to search the web and find an accurate scope of the history of American lynching. The names have always been kept safe but distant, in old archives and scholarly books and dissertations. This site leaves the record open for all Americans, especially high school students who want to learn more than what their textbook has to say,” the site’s authors wrote.

By Stacy M. Brown, NNPA Newswire Senior Correspondent

In the century following the Civil War, as many as 5,000 people of color were murdered by mobs who believed in the cause of white supremacy.

On average, mobs killed nine people per month during the 1890s. Over the next 20 years, seven people each month were victims of lynch mobs.

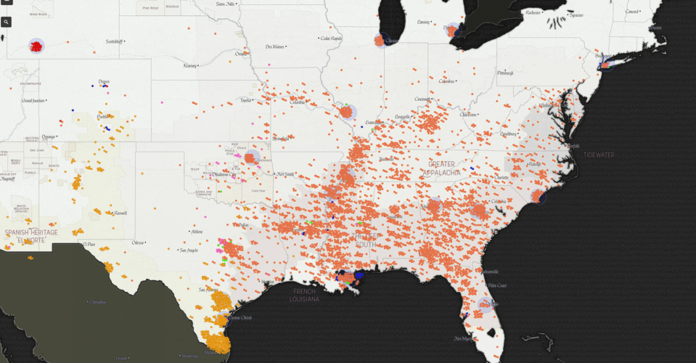

The figures are all according to an interactive map project that tracks the history of lynching in America – state-by-state.

The map is called “Monroe Work Today.”

It is named after a black sociologist, who put together much of the information that details lynchings from 1835 to 1964, the period covered in the map’s data set.

Information found on the map reveals that black men were the most lynched group of people among the documented victims, usually due to mob violence after criminal accusations.

The map, which users can view based on region, also reveals the lynchings of Latinx people, Asians, Italians and Native Americans.

Monroe Nathan Work lived from 1866 to 1945, and the interactive map is called a rebirth of one aspect of his work.

Work was compelled to document every known lynching that was happening in the United States.

“You might already be familiar with what lynching is, and this website will examine it more,” the website’s authors write. “Of course, it starts with an act of injustice: by sentencing someone outside the law with no process or trial. Even worse, at the turn of the century, the methods of lynching had become commonplace, fueled by hatred — and unspeakably cruel. It was Mr. Work’s meticulous recordkeeping that preserves the names that are now an important part of our history.”

Work was known to love sociology for its search for the facts.

According to his biography on the website, sociology enabled Work to demonstrate how African Americans actually lived, in comparison to racist stereotypes.

For example, his work, “A Half Century of Progress,” compares the years 1866 to 1922. Despite enduring slavery and violence prior to 1866, by 1922 black people had increased literacy rates by 70 percent and vastly improved economically. The number of homes owned by black people grew from 12,000 in 1866 to 650,000 in 1922, just 62 years later. In aggregate, black people’s wealth grew by 750 percent, increasing from $20 million to $1.5 billion.

“Before this website, it was impossible to search the web and find an accurate scope of the history of American lynching. The names have always been kept safe but distant, in old archives and scholarly books and dissertations. This site leaves the record open for all Americans, especially high school students who want to learn more than what their textbook has to say,” the site’s authors wrote.

The website provides an education on the definition of lynching.

It doesn’t always mean hanged from a tree.

“There were many ways that a mob could take the life of a victim they were after. Yes, many people died by hanging, but others were killed from a hail of gunshots, dragged to death behind a vehicle, and some were burned alive. Sometimes, the mob would do all of these things to a single person,” the authors wrote.

A victim usually was accused of something. Thus, lynching wasn’t a random attack. Many times, it was utterly trivial and not a crime at all, like talking back to a white person or daring to file a lawsuit.

Some lynchings that were rationalized as defending a women’s honor — a white woman — were actually covering up what were at the time, forbidden relationships. Newspaper articles from the period reveal the flimsy reason was a black man found “hiding under the bed.”

Whatever the charge, it was never allowed to take its course in court. An angry group broke into the jail, pulled the person out, and executed him or her outside the law. Sometimes victims were tortured for a crowd’s amusement.

Some lynchings went far beyond mere murder. They included dark and brutal tortures to a person’s eyes, fingernails, genitals, orifices. People were set afire, or bones were crushed, bodies mutilated, and sometimes cut into pieces. The person died in agony. This kind of cruelty served as a lesson of terror to everyone else who might challenge the status quo.

Further, onlookers showed no signs of guilt for participating.

Many lynchings gathered a large crowd of spectators, like a carnival, and the lynching might be prolonged until more spectators could arrive. For example, the lynching of Sam Hose in 1899 in Georgia caused the railroad to run extra trains to let more people come right after Sunday church. Many photographs exist today because they were taken as proud souvenirs and postcards.

Lynching began as a form of self-appointed justice in local communities in the 1800s, when townspeople made grave accusations first but never bothered to gather the proof. Then as the 1870s turned into the ’80s and onward, lynching became adopted as a terrorist tactic by white supremacists. When slavery was abolished, and as settlers continued to arrive on the West coast, there were very real crusades to change the United States to a place only for whites.

In the South, a mythology arose that lynching was the only way to protect their “gentle women” against a crime wave of rapes. Similarly, in 1933, the Governor of California publicly praised the lynching of one kidnapper by people on the street. He promised to pardon anyone who might be prosecuted for participating in the mob, according to the website authors.

“God made the white into a man and implanted within his breast that determination to always be supreme among races of men,” read an October 29, 1920 article in the Okaloosa News-Journal in Florida. “This is why the white man of the South, standing out boldly tells civilization: ‘I am a white man! I will rule!’ Were he to do otherwise, he would be a renegade to his race.”

To view the map, click here.