By Stacy M. Brown, Senior National Correspondent, NNPA Newswire

When Dr. Benjamin F. Chavis Jr. arrived in Warren County 40 years ago, the Oxford native had no intention of going to jail again.

Chavis, a member of the political prisoner group, The Wilmington 10, had served nearly a decade after false allegations against him and fellow activists.

Now, the Martin Luther King Jr. disciple knew the people of Warren County needed a voice.

The government had determined the predominate Black area as the best place for Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs), a toxin that increases the rates of various cancers.

Police quickly detained those protesting the state’s decision to allow the toxins in the area. Over six weeks, more than 500 people suffered arrests for protesting the PCBs.

Police grabbed Chavis on the way to the protest.

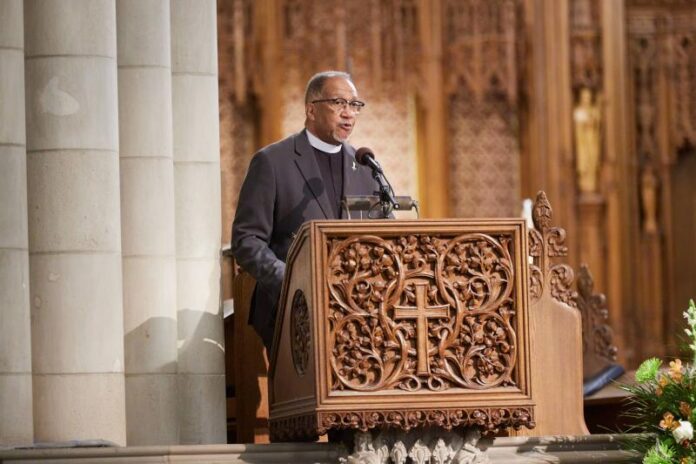

“I think I’m the only person to go to jail for driving too slow,” Chavis told a large and lively gathering at Duke University during the observance of the 40th anniversary of the protests that sparked the birth of the environmental justice movement.

“But there I was, back in a jail cell for protesting with the others,” he stated.

Chavis, the former NAACP President and current President and CEO of the National Newspaper Publishers Association, then coined the term “environmental racism,” which resonates 40 years later.

“The thought that the state would pick this county of all the 100 counties in North Carolina as a dumping site was unthinkable,” stated Chavis, whose start in civil rights began under the tutelage of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

“What started in my favorite county 40 years ago, with the beginning of the environmental justice movement, has grown to a global movement,” Chavis said.

“The demands of millions of people are not only being heard but there are changes.”

For nine months, organizers had remained busy planning commemorative events, which included the NAACP Warren County Branch, Coley Springs Missionary Baptist Church, Warren County Environmental Action Team, Warren County Community Center, and the United Church of Christ, who 40 years ago asked Chavis to go to Warren County.

The slate included the virtual program, “Casting Your Ballot for Environmental Justice,” a webinar discussion with Chavis, former protestor Dollie Burwell, and the Rev. Bill Kearney.

Known as the “Mother of the Environmental Justice Movement,” Burwell said her faith spurred her integral involvement in the protests.

“My faith played a great role in my decision to organize my community, protest, and engage in civil disobedience,” Burwell said.

“Growing up, my parents often recited Micah 6:8. I believe God had given me the tools I needed to organize my community,” she said.

“I learned to speak and organize and developed leadership skills. Prayer sustained me not only through the six weeks of protest but also to lead the Working Group through the detoxification of the landfill.”

Chavis and Burwell also joined a large group at Duke University’s Penn Pavilion Garden Room for a discussion titled “Recalling Warren County Protest.”

“I’m optimistic about the future,” Chavis said later during a discussion at Duke Chapel with Catherine Coleman Flowers titled “Environmental Justice: Past, President, and Future.”

“We now have a vibrant movement all over the world. The strongest movement for change is a movement that is diverse, inclusive, and respectful of our diversity,” Chavis proclaimed. “People see the connection between health, the environment, and health and public policy.”

“We now have a vibrant movement all over the world. The strongest movement for change is a movement that is diverse, inclusive, and respectful of our diversity,” Chavis proclaimed. “People see the connection between health, the environment, and health and public policy.”

For Chavis, the protests were only one part of the movement.

He took the position of executive director of the United Church of Christ’s Commission on Racial Justice (CRJ).

With Chavis at the helm, the CRJ released its landmark 1987 study, “Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States.”

Chavis convened the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit in 1991.

He said those early years of effort endure today as “an effective national and global movement for justice, for environmental justice.”

During the observance of the protest anniversary, Chavis and a contingent of protestors from 1982 and the present day held a commemoration ceremony and march to the landfill site.

“We are victors, not victims,” Warren County Environmental Action Team coordinator Bill Kearney said.

“I believe that what man meant for harm, God can turn to good,” Kearney added while noting that those protests are credited with the birth of the environmental justice movement.