By Ann Levin, Associated Press

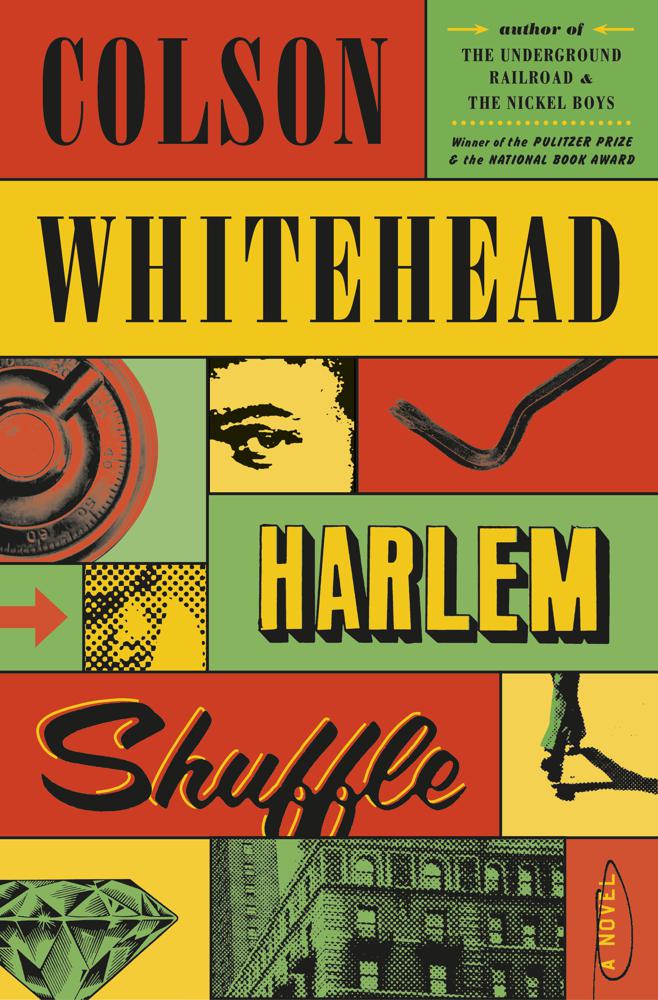

Ray Carney is the kind of outlaw you want to root for because he’s kind, generous, loves his wife and family, and is “only slightly bent when it came to being crooked.” He’s the hard-working, upwardly aspirational anti-hero of “Harlem Shuffle,” Colson Whitehead’s loving homage to noir fiction and nostalgic look at the city that never sleeps in the late 1950s and early ’60s. The book is among this year’s finalists for the Kirkus Prize.

Unlike his last two books, “The Underground Railroad” and “The Nickel Boys,” which dealt with the serious social justice themes of slavery and Florida’s segregated juvenile justice system, “Harlem Shuffle” is a wildly entertaining romp. But as you might expect with this two-time Pulitzer Prize winner and MacArthur genius, Whitehead also delivers a devastating, historically grounded indictment of the separate and unequal lives of Blacks and whites in mid-20th century New York.

Like a lot of heist novels, the plot is twisty, with a large, at times bewildering cast of characters and a few storylines that border on the ridiculous. What ties it all is the utterly believable, complicated character of Carney, a furniture store owner and small-time fence desperately trying to claw his way into the middle class.

The plot is set in motion when Carney’s hapless cousin Freddie gets involved in a brazen plot to rob the historic Hotel Theresa, introducing Ray to an unsavory but colorful cast of killers, conmen and assorted ne’er-do-wells. Carney gets in deeper and deeper, largely out of loyalty to Freddie, who was like a brother to him growing up.

But it’s not as simple as that. Carney also has his own demons, primarily a massive chip on his shoulder and overweening thirst for revenge. It might be because his hoodlum dad abandoned him and his mother. Or because his in-laws look down on him because his skin color is darker than their beloved daughter’s. Or because of the daily indignities he faces as a Black man in America — or all three.

Part of the suspense — and what sets this novel apart from so many others in the hard-boiled crime genre — comes from wondering whether Ray’s better angels will prevail. In one of countless beautifully written, erudite passages, Whitehead takes us inside Ray’s head as he considers the relationship between fathers and sons, and the question of whether genetics is destiny. “Carney’s father was crooked, but that didn’t make him so. It simply meant that he knew how things worked in that particular line.”