By Erick Johnson, Courtesy of The Chicago Crusader

April 4, 1968 began as an ordinary day in America.

In Chicago, Mayor Richard J. Daley was prepping the city for the 1968 Democratic National Convention at the Conrad Hilton Hotel. With Blacks supporting Robert F. Kennedy.

In Memphis, King, a 39-year-old Baptist preacher was staying at the Lorraine Motel, a Black-owned, two-story structure operated by Walter Bailey.

King wasn’t supposed to be at the Lorraine or in Memphis. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover accused him of living large by staying at a Holiday Inn in Memphis, according to author Gerald Frank in his book, An American Death: The True Story of the Assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Greatest Manhunt of our Time.

After a peaceful demonstration on March 28 ended in violence, King was advised not to return to Memphis. Downtown shops were looted, and a 16-year-old was shot and killed by a policeman.

King wanted to return to Memphis to lead a march for the Black sanitation employees who were striking for better wages and working conditions after two workers were crushed to death by a malfunctioning garbage truck.

He was also facing heavy criticism for his stance against the Vietnam War and his plans to take his Poor People’s Campaign to Washington. But his plans to return to Memphis—a city with intense racial history—drew the most concern.

King decided to go to Memphis after having a heated argument with Marian Logan, a close friend and secretary of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Logan’s husband, Dr. Arthur Logan, was a physician and top fundraiser for the Black organization that King founded. The Logans were friends with King, but Marian was strongly against the march in Memphis and urged King to cancel the trip.

According to Frank’s book, in late March, King showed up at the Logan’s residence in New York. The couple and King argued through the night about taking the April trip to Memphis. The argument ended without a resolution. King had been on sleeping pills prescribed by his physician, but the drugs weren’t working.

King eventually got his way after a telephone call on April 3 where Marian told him, “If you don’t get yourself out of there, you’re going to get yourself killed.” King replied, “Marian, I’ve been trying to tell you darling, I’m ready to die,” according to Frank’s book.

Located at 450 Mulberry Street in Memphis, King would check into room 306 at the Lorraine Motel with his closest advisor Reverend Ralph Abernathy. Reverend Jesse Jackson would be next door in room 305.

In room 5B at a rooming house across the street was John Willard, a.k.a James Earl Ray, a young white ex-convict who used the alias to check into the rooming house.

Despite concerns about the Memphis march, King was reportedly in a good mood after successfully delivering his famous, “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech the night before at the Mason Temple.

That day, April 4, King spent the day working with local leaders on his plans to take his Poor People’s March to Washington later that month.

After being shot, King was rushed to St. Joseph Hospital, a Catholic institution that was just two miles from the Lorraine Motel. There, a dozen doctors worked on King. A tracheotomy was performed to give King an airway allowing him to breathe. Despite all the efforts, King died at 7:05 p.m.

Days later, ironically Loreen Bailey, the wife of the owner of the Lorraine Motel, died after suffering a stroke.

According to reports, Jackson called King’s wife, Coretta, in Atlanta and told her that her husband had been shot but did not say he died. Coretta learned the bad news from King’s longtime secretary, Dora McDonald.In Gary, Hatcher was with Democratic presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy the morning of April 4, 1968. Kennedy had been campaigning for the White House in Gary. He left the city at 3 p.m. for other Indiana cities, arriving at the Broadway Christian Center where he announced King’s death to a crowd of about 500 Blacks at 9 p.m.

Fearing a race riot, Indianapolis Mayor Richard Lugar told Kennedy’s staff that his police could not guarantee Kennedy’s safety at 17th and Broadway. Kennedy gave the news anyway.

That evening, two months before his own assassination in June 1968, Robert F. Kennedy delivered a speech that became one of the most inspiring in American history.

“What we need in the United States is not division; what we need in the United States is not hatred; what we need in the United States is not violence or lawlessness, but love and wisdom, and compassion toward one another, and a feeling of justice towards those who still suffer within our country whether they be white or whether they be Black,” Kennedy said.

For the next several weeks, Black America and the nation would go into a period of deep mourning.

Chicago Alderman Michelle Harris (8th) said, “I have limited memories of that day because I was only six-years-old when Dr. King was assassinated. However, what I do remember was the sadness that came over my grandparents and our entire household. I didn’t totally understand the impact of his death until I was a little older.”

For the first time in American history, a sitting president ordered that flags be flown at half-staff for a Black man.

Thousands turned out for two funerals for King in Atlanta.

At 10:30 a.m., one service was held at the historic Ebenezer Baptist Church where King preached. Mourners followed the order of service, reading from a 16-page printed funeral program. Black America’s Who’s Who attended, including Harry Belafonte, the Supremes, Sammy Davis Jr., and Eartha Kitt. Chicago’s Mahalia Jackson, a close friend who spurred on King during his famous “I Have a Dream Speech” in 1963, sang King’s favorite hymn, “Precious Lord, Take My Hand.”

Following the services, King’s casket was borne on a horse-driven carriage to his alma mater, the historically Black Morehouse College. Thousands lined the procession route before a second service was held at the all-male school at 2 p.m.

King was originally buried at Atlanta’s predominantly Black South View Cemetery, but his remains were reinterred in a crypt at his Center for Nonviolent Social Change after threats of vandalism on King’s original grave.

King’s death added more fuel to the growing Black Panther movement, which at times, clashed with King’s nonviolent message with its militant approach to fighting racism and segregation.

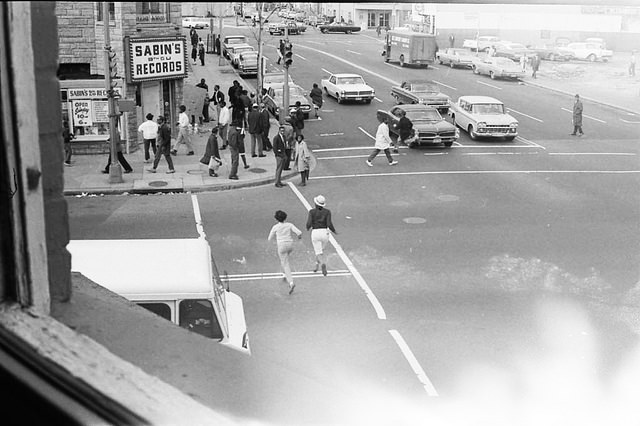

President Lyndon Johnson appealed for calm as riots erupted in some 108 major cities, including Chicago, New York, Philadelphia, Atlanta, Boston and Pittsburgh.

King’s assassin, James Earl Ray, used a Remington 30-06 rifle to kill King. Before his crime, Ray briefly worked at the defunct Indiana Trail restaurant in Winnetka on Chicago’s North Shore.

In 1967, he escaped the Missouri State Penitentiary, where he was serving a 20-year sentence for robbing a supermarket. An international manhunt led to his capture at London’s Heathrow Airport. Coretta Scott King learned of his arrest while attending the burial of Robert F. Kennedy in June at Arlington National Cemetery.

Ray pleaded guilty to killing King, but recanted his confession. He was serving a 99-year sentence when he died of liver failure at Columbia Nashville Memorial Hospital in Nashville, TN on April 23, 1998.

Until the day she died, Coretta Scott King said that Ray did not murder her husband—a belief shared by many Blacks who suspect FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover and the U.S. government were involved in King’s assassination.